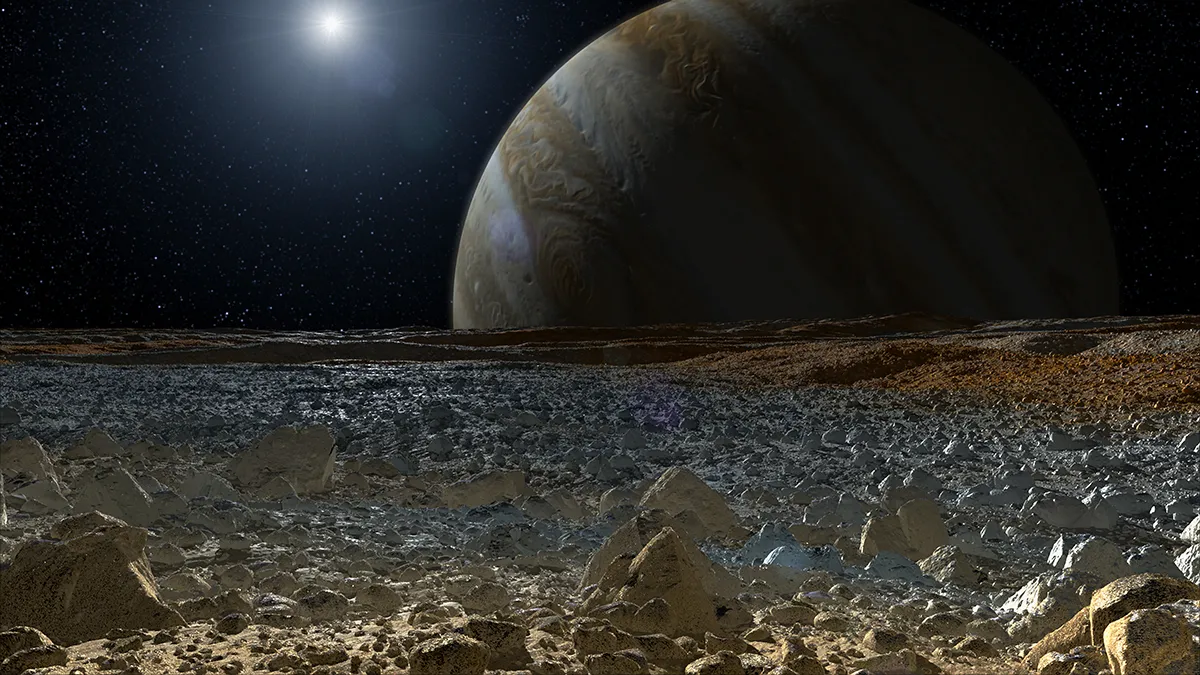

Jupiter's icy moon Europa is among the most promising places in the Solar System to search for life beyond Earth.

Like Saturn's moon Enceladus, there is strong evidence that Europa has a subsurface liquid ocean beneath its icy crust, and if life on Earth has taught us anything, it's that where you find water, you often find life.

More space science

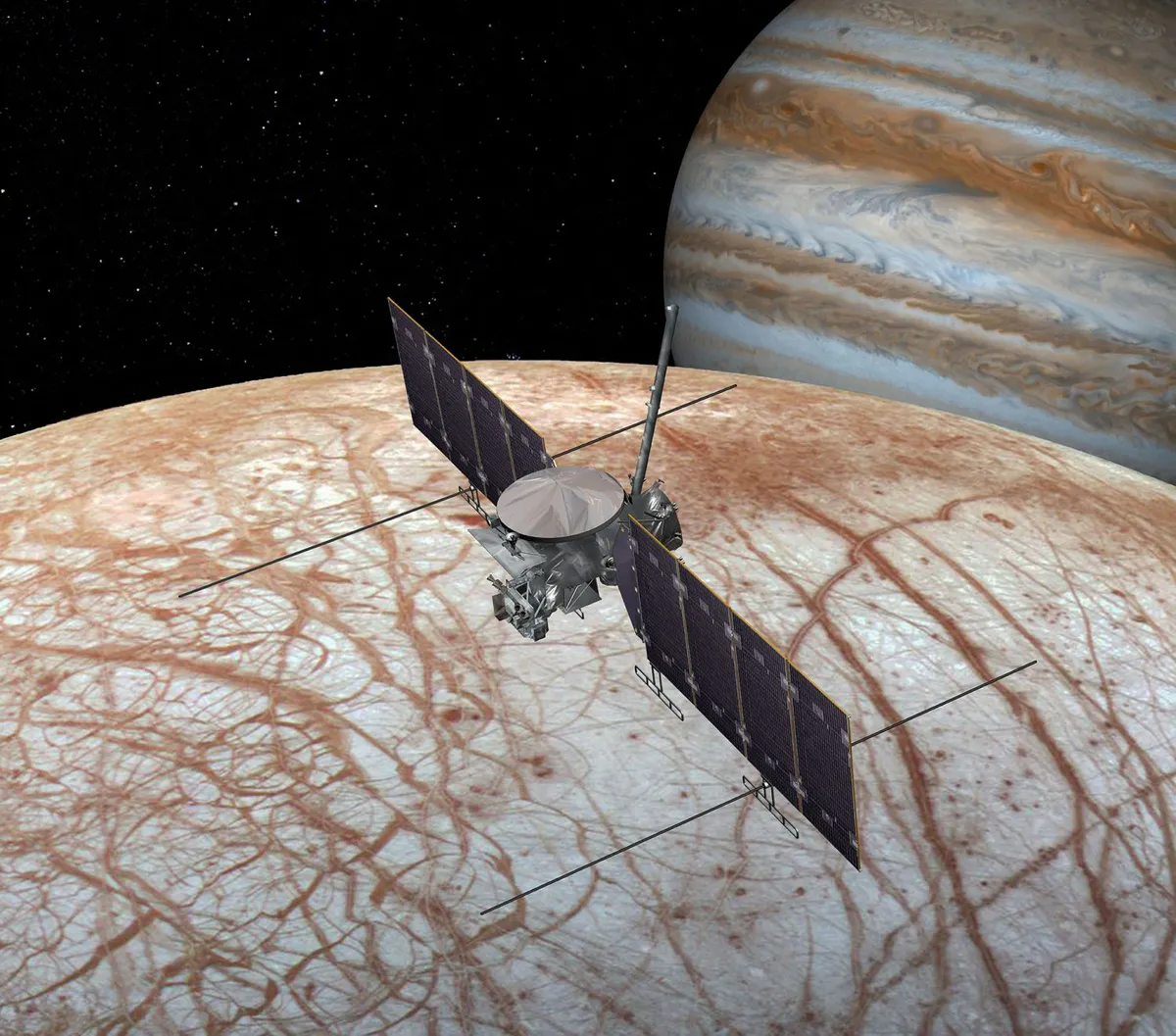

Two upcoming missions, NASA's Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency/NASA collaboration JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) are set to give planetary scientists more data to study in the analysis of Europa as a potentially habitable world.

A study by Murthy Gudipati and Bryana Henderson at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory along with Fred Bateman at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, looked at Europa's potential habitability and discovered something quite spectacular: the icy moon may glow in the dark.

We spoke to Dr Murthy Gudipati, principal scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to find out more.

Why study Europa?

Europa is thought to have liquid oceans in its interior covered by very cold ice, which is in contact with its rocky core and absorbs minerals.

There is also an expansion and contraction of Europa taking place because of the tidal force of Jupiter, so there is energy being generated inside.

As we know, for life we need minerals, water, energy and organics, and as these things seem to be available on Europa, people think its interior could be habitable.

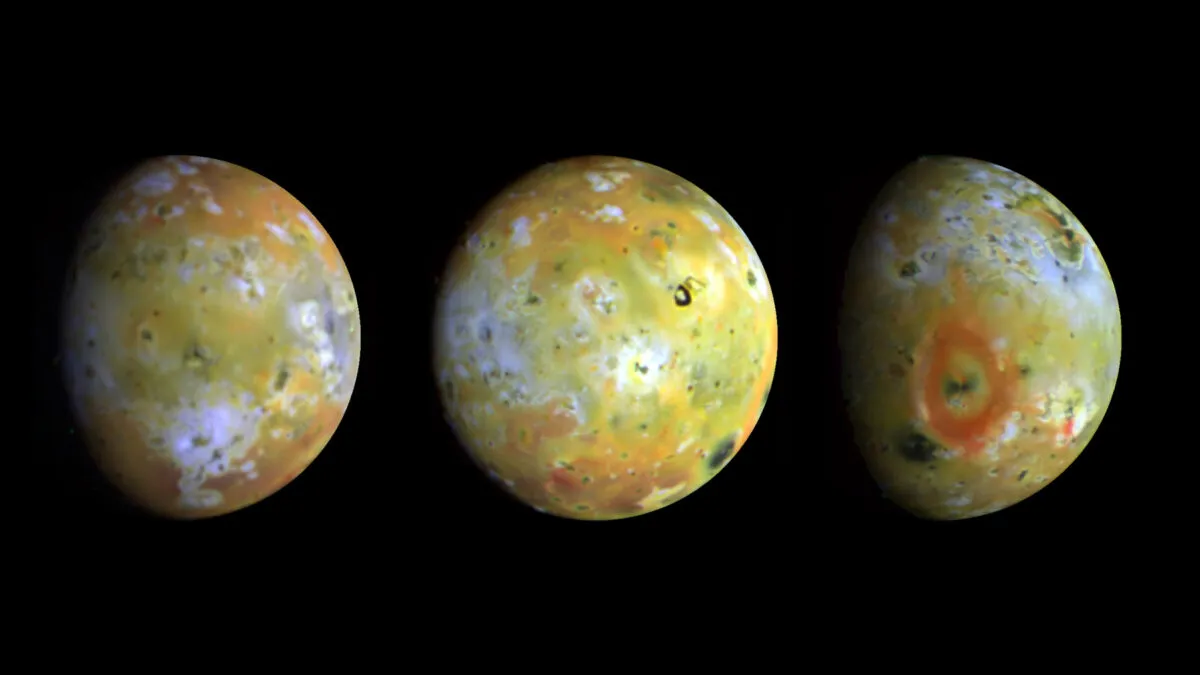

Europa is in a unique situation as one of the four big Galilean moons around Jupiter, a planet with a very strong magnetic field.

Because of this and because Io, the closest moon, has extremely high volcanic activity (as discovered by Voyager scientist Linda Morabito), you get ions and electrons generated and accelerated by Jupiter’s magnetic field, meaning Europa’s surface gets a very high dose of radiation.

So while the interior could be habitable, the surface is absolutely not.

One of our original research aims was to understand how deep the electrons penetrate through Europa’s surface. The deeper they go the more damage they could do, particularly to organic material.

Our aim was to see how organic matter would be destroyed if brought up to the surface from the oceans.

How did you simulate Europa’s conditions on Earth?

We needed an instrument that could hold several tens of centimetres of ice core close to 100K (–173ºC), so we built the Ice Chamber for Europa’s High-Energy Electron And Radiation-Environment Testing (ICE-HEART).

We took it to the USA’s National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland where they have a high-energy electron source.

The experiment was contained in concrete and lead walls with sensors deployed, and to understand what was happening visually we also deployed a camcorder.

We set out to analyse data to determine how deep the electrons go and the secondary radiation [X-rays] coming out.

The primary goal was to understand this, and also how the frozen ice-salt mixtures differ from pure water ice. The glow came as a surprise – as serendipity.

What happened when you switched off the lights?

We saw that the area on the ice where the electrons were bombarding was glowing.

From water ice we went to brine, but there was no glow; so we thought there was something wrong; we then went back to water and it was glowing.

That was the “Aha” moment for us. We realised the glow was coming from the ice and it’s somehow determined by the composition of the ice.

Is Europa habitable?

If NASA’s Europa Clipper mission is able to see effects similar to those we found, the observations would help us to determine the surface composition.

Europa is supposed to have a young surface, which means that the surface to sub-surface exchange is happening within 50 to 60 million years. That is very young: our Moon’s surface is billions of years old.

So we can use the surface composition and model how it maps to the ocean composition. We cannot say about life, but based on determining the surface composition, particularly salinity, we can get estimates of ocean salinity.

In turn, that could be compared to our own ocean salinity to see if it is conducive to life.

What colour is Europa's glow?

For colour, we probably need to use our imagination! We derived approximate colours based on the spectral distribution.

For water ice, on average this looks like a whitish glow, but then magnesium sulphate has more glow into the red, and sodium sulphate also has some into the red, while other minerals have a stronger glow in blue.

I would say Europa’s expected to have a whitish glow with a bluish, greenish or red tinge – maybe like a mosaic if we have different compositions.

When the Europa Clipper visits, it would be wonderful to see Europa’s glow on its nightside.

This interview appeared in the February 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.