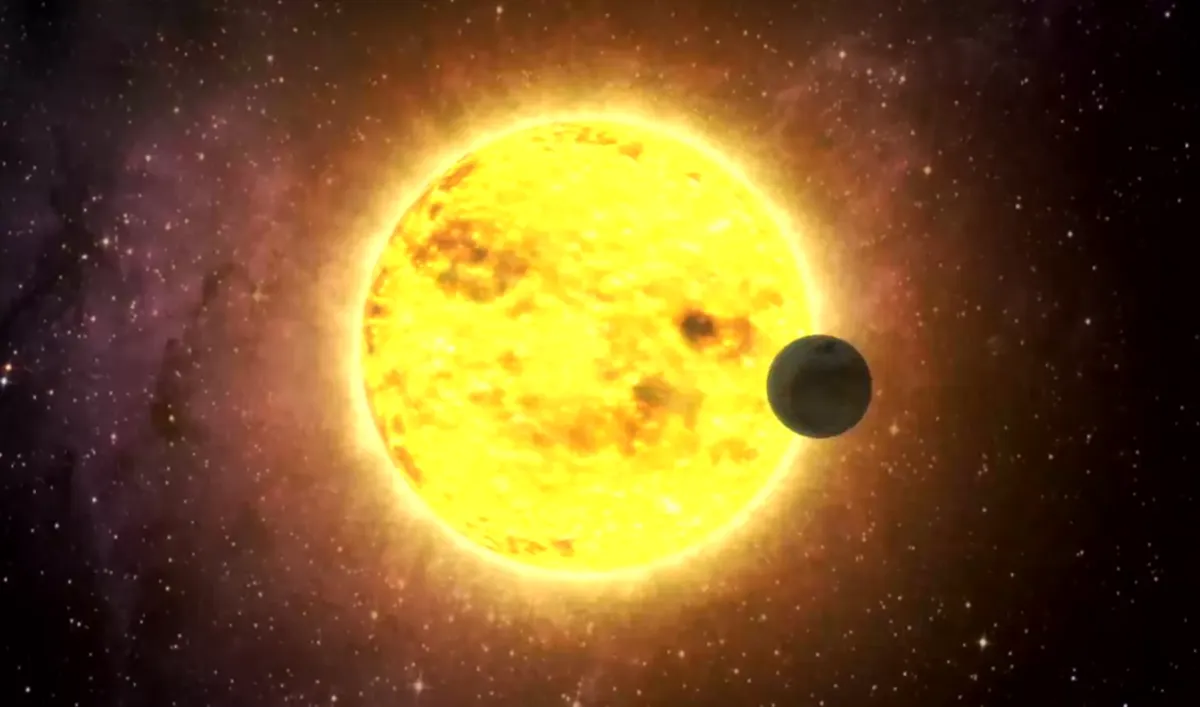

There are several ways of detecting exoplanets, but the vast majority are found using the transit method.

Exoplanets are planets orbiting stars beyond our Solar System, and as such they can be hard to spot against the bright light of their host star.

But the transit method is one particularly successful way astronomers can detect exoplanets.

Astronomers carefully monitor a star, looking for a brief, tell-tale dip in the star’s brightness as a planet passes across – or transits – briefly blocking out the starlight.

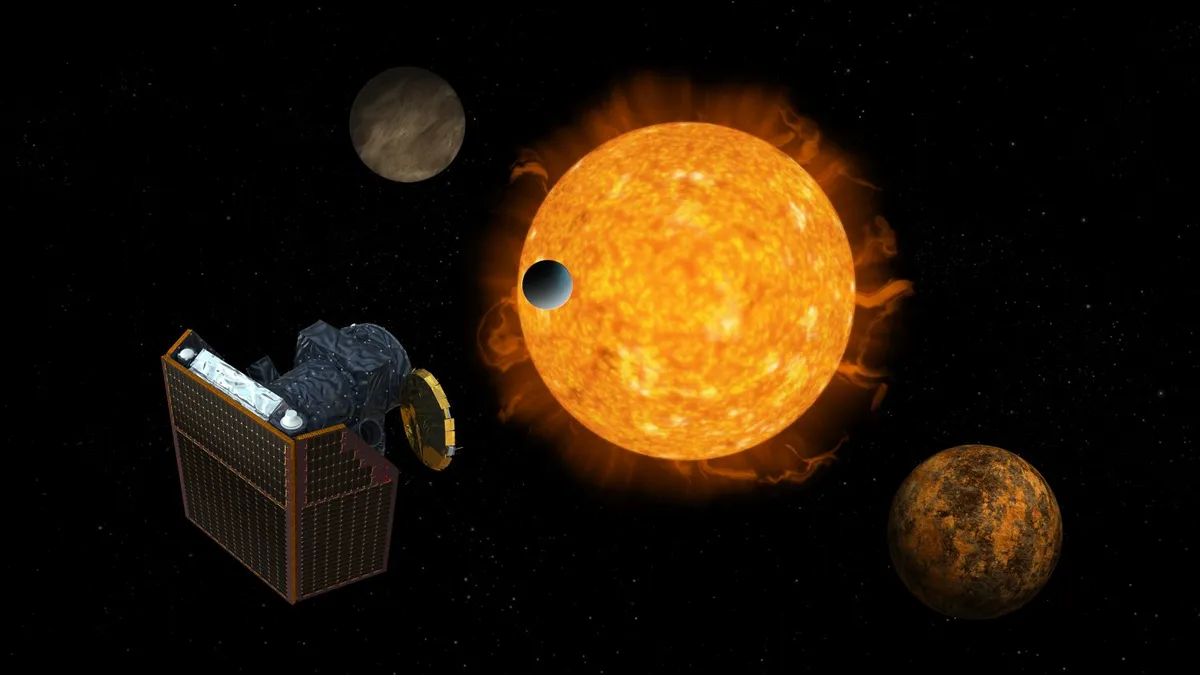

The time between dips reveals how long the planet takes to orbit the star, and so how far out it is.

The dip’s depth is determined by how much light the planet blocks, showing its physical size or radius.

Measuring mass in transiting exoplanets

Once at least three dips have been found, it is considered a planetary candidate, but it still needs its mass measured to be a confirmed world.

To do this, astronomers measure the effect the planet’s gravitational pull has on other objects in the system.

If there are multiple planets, then their orbital times will be slightly irregular as they pull on each other.

For most cases, though, astronomers have to undertake follow-up observations of the host star, looking for signs of a slight wobble as the planet pulls it to and fro.

Planets can only be detected by the transit method if they block out enough light to be noticeable against the bright glare of the star.

The closer a planet is, the bigger the dip, meaning most transiting exoplanets have orbit times of just a few days or weeks.

While larger planets are easier to spot, it is possible to detect smaller worlds, provided they are in orbit around dimmer stars, such as red dwarfs.

What's more, astronomers can analyse the starlight that passes through the exoplanet's atmosphere to search learn more about its chemical composition.

This method can even be used to detect biosignatures, signs of life, in planets orbiting distant stars.

This guide appeared in the February 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine