Over 400 years ago in 1608, Dutch optician Hans Lippershey filed a patent for his new invention, the refracting telescope. Astronomy would never be the same again.

In the centuries since, telescopes have helped us glimpse the farthest reaches of the Universe and begin to unpick its secrets.

From the personal telescopes Galileo and Newton kept in their observatories, to the colossal telescopes that have to be built into the sides of mountains, below we're taking a look at some of the most important and famous telescopes that have made - or hope to make – the biggest impacts in the field of astronomy.

Galileo's telescope

In May 1609, Galileo Galilei learned of a remarkable new invention from the Netherlands that used lenses to make distant objects look as if they were nearby.

Such a device could finally bring the heavens he studied into view, so he set about creating his own versions and increased the magnification up to 20x.

Surely one of the most famous telescopes of all time is Galileo's own: this was the beginning of observational astronomy as we understand it today.

One of Galileo’s first targets was the Moon and his telescope revealed the craters and mountains on its grey surface. He also observed the next brightest object in the night sky: Jupiter.

On 7 January 1610, he noticed it was joined by “three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness” that seemed to align perfectly with the planet. Over the next few nights he found they weren’t fixed at all, but moved with Jupiter.

On 13 January he noticed a fourth. These weren’t stars, but moons orbiting the planet, and they would later become known as the Galilean Moons.

By March, Galileo had published his findings in his seminal book, Sidereus Nuncius. It provided compelling evidence that Copernicus was right in his theory that the Sun, not Earth, was at the centre of the Universe, and that the telescope would be the most powerful tool yet for exploring the cosmos.

Follow our DIY guide and build your own Galilean telescope

Isaac Newton's telescope

By the mid-17th century, a common lament was heard among astronomers: why were there coloured bands at the edge of their telescope’s view?

It was Sir Isaac Newton who realised this effect, known as chromatic aberration, was created by the edge of the telescope lens acting like a prism and splitting the white light of stars into disparate colours.

Several telescope makers were attempting to fix the problem by using mirrors, instead of lenses, to focus light

The theory was sound, but was proving difficult to put into practice. Ideally, you’d need a parabolic mirror, but these were hard to produce by hand.

Newton used a spherical mirror, which was easier to grind.

This solved the chromatic aberration, but introduced another optical defect, spherical aberration, where the image doesn’t focus uniformly.

Newton also used a secondary mirror so the image could be viewed more easily from the side of the telescope.

Newton showed his telescope at the Royal Society of London in 1671 and it was such a hit that he was asked to demonstrate it to King Charles II.

Fifty years later in 1721 another astronomer, John Hadley, worked out how to create parabolic mirrors, eliminating the spherical aberration.

Today the Newtonian design is the foundation of almost every reflecting telescope available on the market.

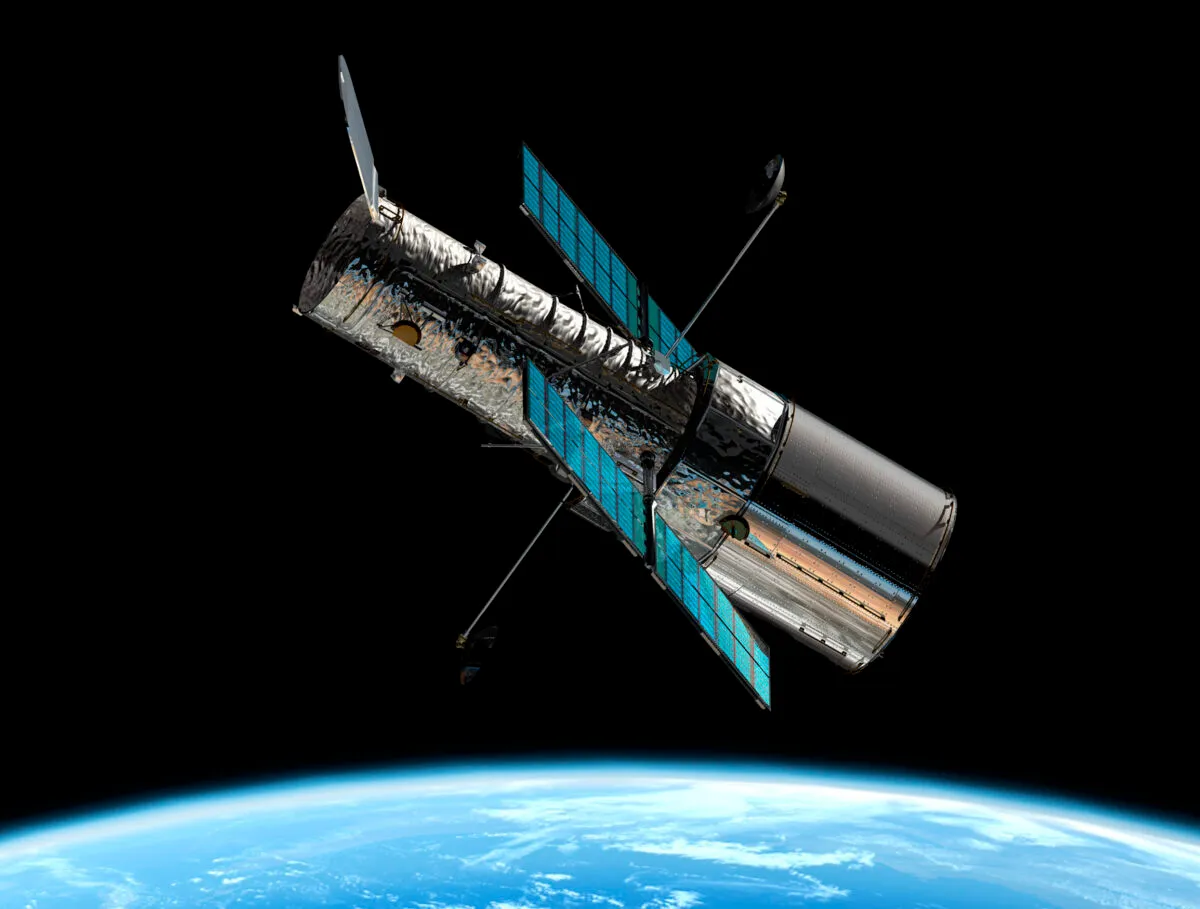

Hubble Space Telescope

The most famous of all modern space telescopes is potentially the Hubble Space Telescope (and this certainly would have been the case a few years ago, before the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope).

Astronomers have long dreamed of putting a telescope in space. Above the clouds and able to point away from the Sun, such a telescope could observe 24 hours a day without atmospheric disturbance or light pollution.

But it would take until 1990 – and the work of both NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) – to make the dream a reality.

On 24 April that year, the first ever visual space telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, launched into orbit.

But the joy of launch was short-lived when it became apparent that there was a flaw in Hubble's mirror. The 2.4m-wide mirror was too flat.

The error was around 1/50th the thickness of a human hair, but it stopped the mirror focusing properly and its images were blurred. Fortunately, Hubble was made to be upgraded.

In December 1993, the first Hubble servicing mission installed a new instrument to fix the problem, bringing the Universe sharply into focus.

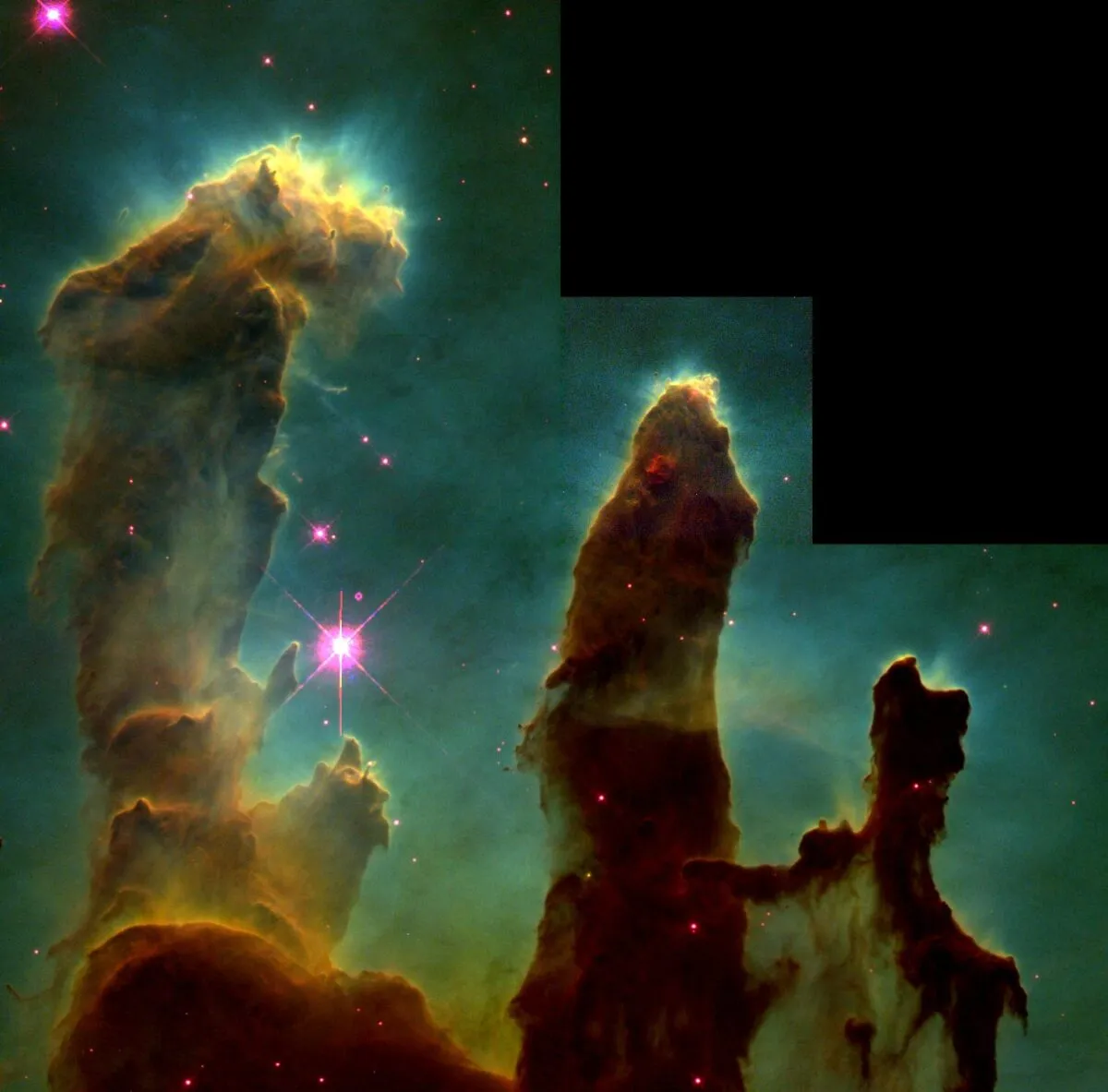

Over the last 30 years, Hubble has revolutionised our view of the cosmos, imaging everything from neighbouring planets to distant galaxies.

Its data has been used in over 15,000 science papers while its images have become part of popular culture.

More recently, it was feared that Hubble’s days might soon be over. In June 2021, a computer fault shut down the telescope, but operators have re-established contact and fixed the problem.

It now looks like the reign of Hubble is set to continue.

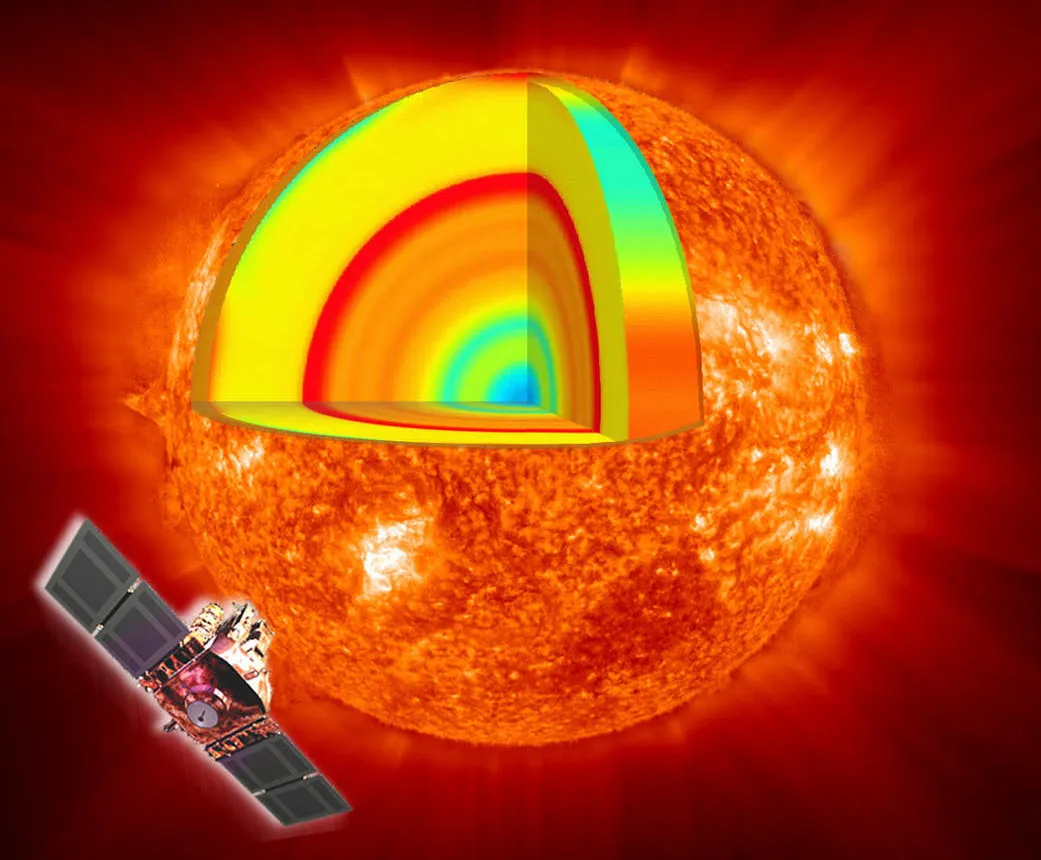

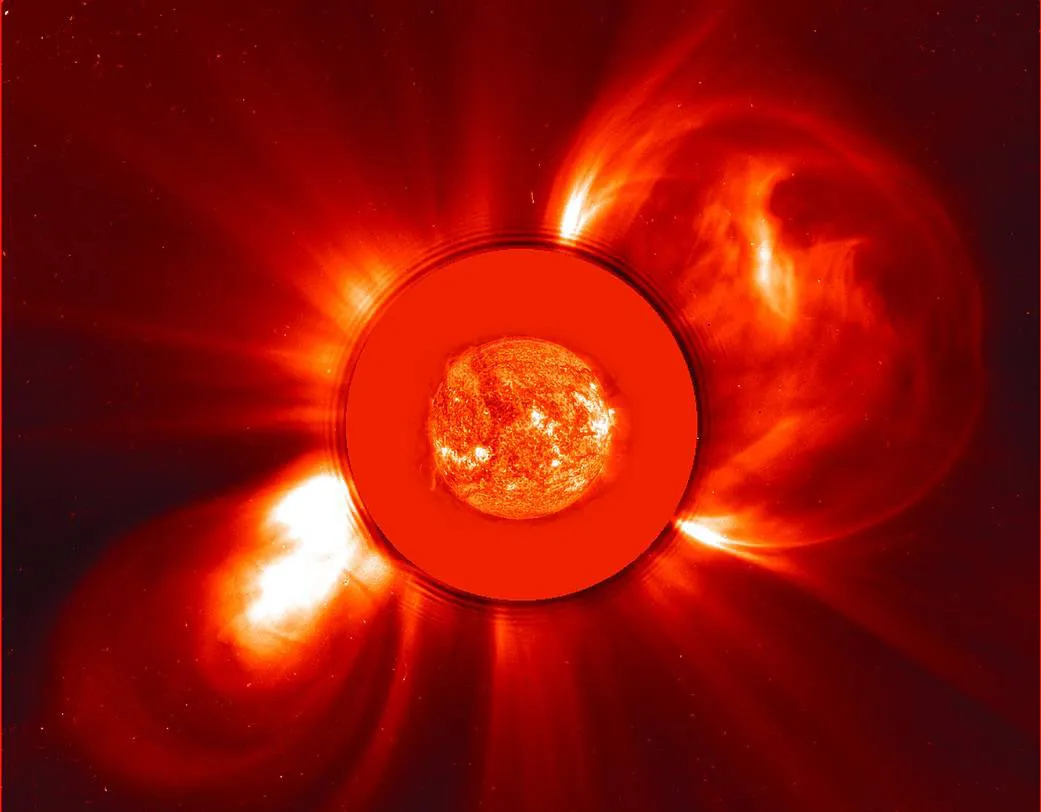

Solar and Heliospheric Observatory

While most telescopes are pointed away from the Sun, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) has spent the last 25 years looking at it.

The spacecraft, a joint mission by ESA and NASA, was meant to study the Sun for just two years, investigating its expansive outer atmosphere, surface and internal structure.

This meant astronomers could predict solar storms, which can harm astronauts and damage space hardware, a week earlier than before. It launched in 1995, but has proved so useful that its mission has been extended multiple times.

For over two decades, SOHO has provided a near real-time view of the solar surface, allowing astronomers to predict solar storms earlier than they could before.

Its watch has extended through two of the Sun’s 11 year-long solar cycles, giving insights that enable astronomers to accurately forecast space weather trends over decades rather than days.

Arecibo Telescope

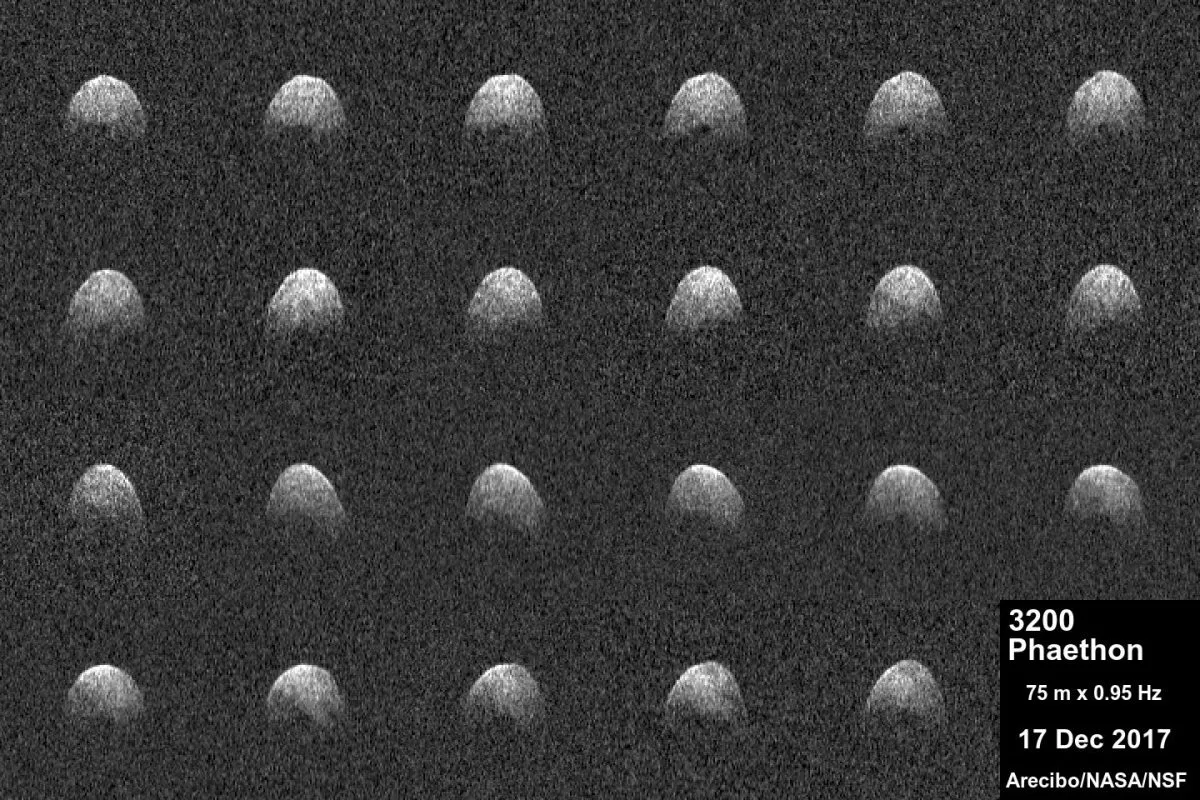

Built into a sinkhole in Puerto Rico, the 305m-wide Arecibo telescope reigned as the largest radio telescope in the world for over half a century.

And yet when it was first put to use in 1963, its primary purpose wasn’t scientific, but military – detecting missiles bound for the US. In 1967 however, it was transferred to the National Science Foundation, becoming a scientific facility.

The first change made was the installation of S-Band radar equipment, which could observe Solar System objects as far out as Saturn.

This was used to create radar maps of Mars ahead of the Viking lander missions, as well as glimpsing beneath the clouds of Venus and finding ice on Mercury.

Looking further afield, Arecibo has detected the faint signals from distant radio sources and was key in studying pulsars.

In 2007 it detected the first repeating fast radio burst, proving that they aren’t caused by one-off cataclysmic events such as stellar collisions.

The telescope lasted 57 years, but in August and November 2020, two of its support cables snapped, damaging the dish.

It was due to be decommissioned, but on 1 December a third-cable breakage caused a support tower to collapse, completely destroying the telescope.

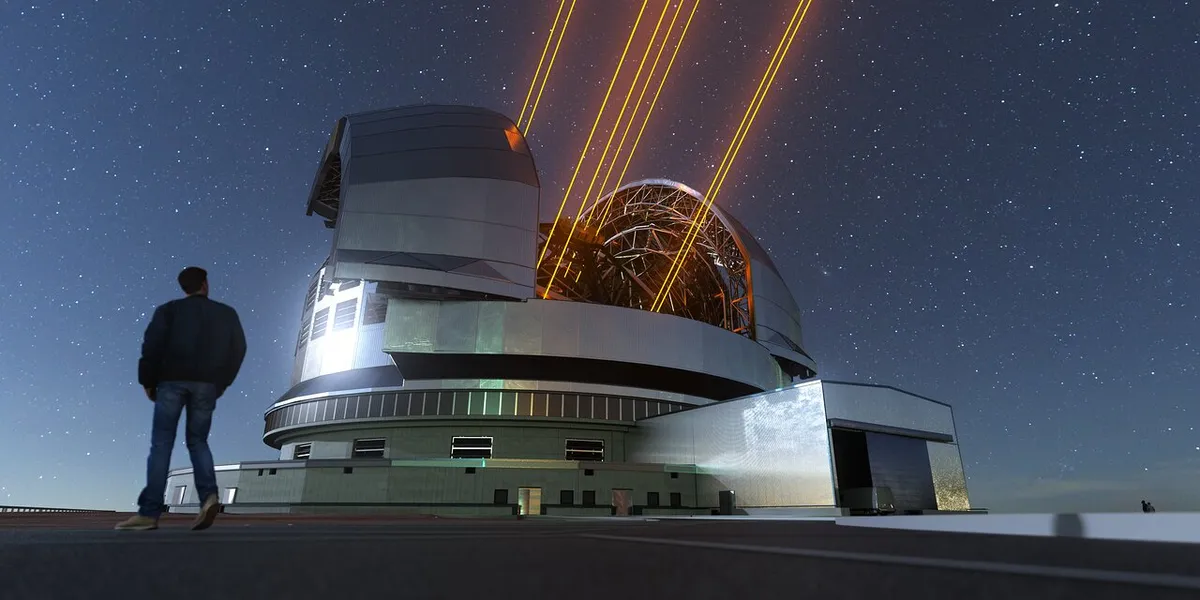

Extremely Large Telescopes

When it comes to astronomical telescopes, bigger is better. A larger dish gathers more light and increases the resolution, making detail sharper.

For telescopes on Earth, however, once mirrors get beyond a few metres wide, atmospheric seeing – where the shifting atmosphere distorts incoming light – blurs the image. This makes building anything larger pointless.

Until 1990, that is, when the European Southern Observatory (ESO) pioneered a new technology called adaptive optics, which subtly deforms the shape of the mirror to correct for the effects of seeing.

Now the only limitation was how big you could make your mirror, leading to a new generation of telescopes dubbed Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs) that will look deeper and with more precision than anything that has gone before.

There are two ELTs currently in construction.

The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) will have a 30m-wide mirror and is being built on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, with an expected first light in 2027.

Elsewhere, the 39.3m-wide European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) is being built in Chile, ready to start observing in 2025.

Building such large mirrors is a challenge: both mirrors are being split up into dozens of hexagonal sections that will be placed together in a honeycomb to create one giant mirror surface.

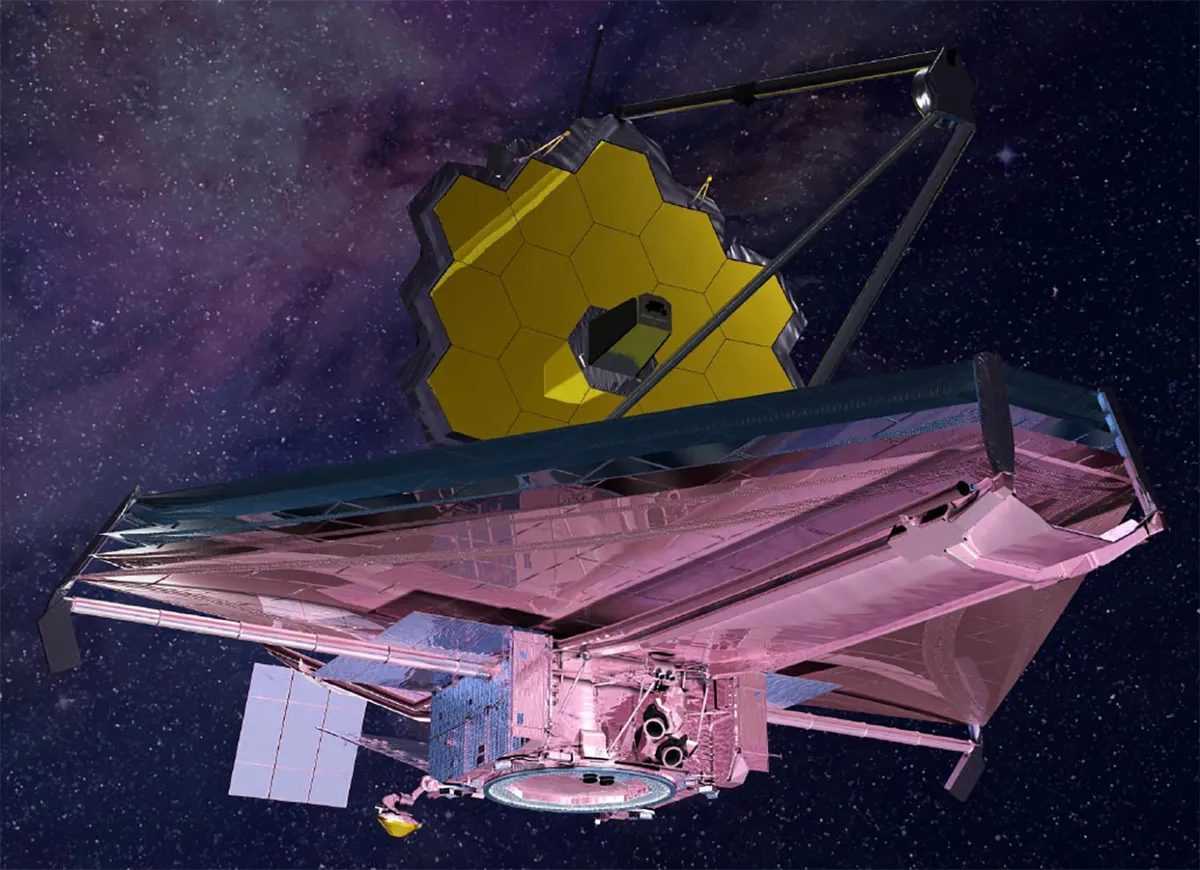

James Webb Space Telescope

In 1996, Hubble’s glorious images had been making headlines for several years and NASA, keen to follow up on its success, began working on what’s now known as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The JWST’s main science goals are to look at how galaxies, stars and planets have grown from the earliest eras of the Universe to today.

To do this, Webb observes infrared radiation, which can pass through the dust in space that obscures visible light, allowing it to peer into the stellar nurseries and the cores of active galaxies.

The radiation also allows it to see objects, such as planets, which are too cool to glow in the visible spectrum.

However, as the telescope’s own heat produces infrared energy, JWST is being kept shaded from the Sun’s heat with a huge sunshield.

This has proved to be the telescope’s most troublesome component.

The shield is made of five layers of delicate foil, each the size of a tennis court, one of which tore in 2018 causing the entire mission launch to be pushed back.

The James Webb Space Telescope launched on 25 December 2021, and since then has been sending back amazing images of the Universe.

Take a look at the James Webb Space Telescope's latest images.

What do you think are the most influential, important telescopes of all time? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.