What are, or were, the world’s greatest telescopes? I do not refer particularly to size; I mean the telescopes that, in their time, reigned supreme and led to ‘quantum leaps’ in science

I can list six of the most famous telescopes in history:

- Galileo’s original refractor

- Isaac Newton’s first reflector

- The Rosse Leviathan at Birr Castle

- The Mount Wilson 100-inch

- The Palomar 200-inch

- The Hubble Space Telescope

More astronomy history

All are still in working order; although the first of them has not been turned skyward for a long time!

Let's take a look at these famous telescopes in a bit more detail, shall we?

Galileo's original refractor

We begin in the winter of 1609/10 in Holland: a telescope had been built by a Middleburg spectacle-maker, Hans Lippershey.

It was probably not the first but reports of earlier telescopes are vague and Lippershey’s is the first about which we have definite information.

News of the device reached Galileo Galilei in Pisa and "sparing neither trouble nor expense" the Italian scientist made a telescope of his own.

Up to then, astronomical observations had been made solely with the naked eye, the limitations of which are obvious.

But in a few weeks, early in 1610, Galileo made a series of spectacular discoveries that changed our outlook forever.

He saw the craters of the Moon, the phases of Venus, the “myriad stars” of the Milky Way and – perhaps most importantly of all – the four main satellites of Jupiter still known as the Galilean moons.

All these discoveries led to the realisation that the Sun, not Earth, is the centre of our planetary system.

Galileo was accused of heresy and condemned by the Inquisition, and it was almost four centuries before the Vatican admitted that he had been right.

Fancy a DIY project? Build your own Galilean telescope.

Isaac Newton's reflecting telescope

Next, the tiny reflector made by Isaac Newton and demonstrated to the Royal Society in 1672.

Galileo’s telescope was, of course, a refractor and apart from various other defects it produced false colour – a lens does not refract all wavelengths equally.

Newton could see no way around this problem and so he decided to collect the light with a curved mirror.

It worked and his prototype telescope is still in the possession of the Royal Society, or so we think.

Suggestions that it may be a later copy have been officially discounted.

Lord Rosse's Leviathan

Now we come to 1845 and the 72-inch reflector made by the Earl of Rosse – an Irish nobleman whose home was Birr Castle, near Athlone in Ireland.

He was not a professional scientist but he was deeply interested in astronomy and began to make reflecting telescopes.

He made a conventional 36-inch and then decided to attempt a telescope with twice this aperture.

The mirror would be made of speculum metal, an alloy of copper and tin; glass mirrors of any real size were too difficult to make in the mid 19th Century.

Lord Rosse built a forge, cast the mirror and made a mounting for it.

The resulting telescope was extraordinary: the huge wooden tube was mounted at the bottom between two stone walls.

It could swing for a limited distance to either side of the meridian, covering a narrow strip of sky; you had to wait for Earth’s rotation to bring your target into view.

Almost as soon as Lord Rosse had completed the telescope he found that the ‘starry nebulae’ were spirals, shaped like Catherine wheels.

We now know them to be galaxies (following astronomy's Great Debate) far beyond the confines of our Milky Way.

After 1909 the telescope fell into disuse but it has now been restored and is fully operational once more.

Until 1917, the ‘Leviathan’ remained the largest telescope in existence, although it had been overtaken in performance by great refractors such as the Meudon 33-inch in France and the Yerkes 40-inch in the US.

Mount Wilson 100-inch reflector

Now we move on to George Ellery Hale, a young American astronomer who wanted to build powerful reflectors and had the knack of persuading friendly millionaires to finance them.

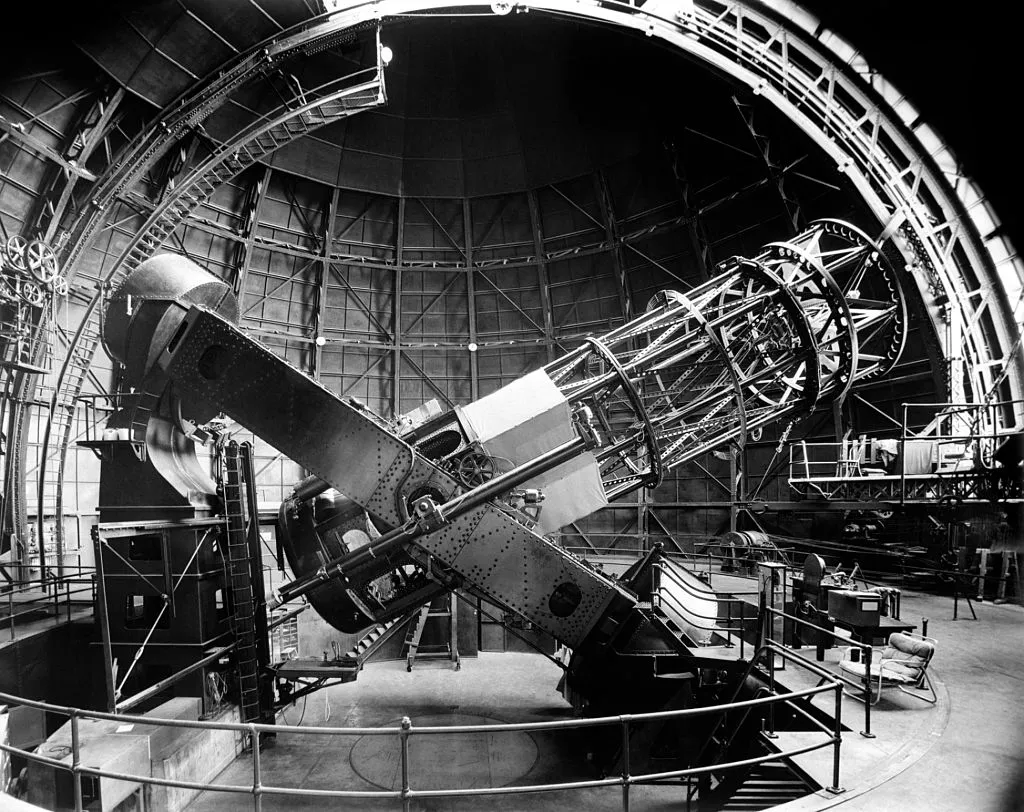

He set up the 100-inch reflector on Mount Wilson, California, which was in a class of its own for over 30 years.

It could show faint objects and fine detail beyond the range of any other instrument.

In 1923, Edwin Hubble used it to identify Cepheid variables in several of Lord Rosse’s spirals, including M31, the Andromeda Galaxy.

Up to that time, astronomers had argued about the nature of the spirals: were they parts of the Milky Way or galaxies in their own right?

As soon as Hubble found his Cepheids the question was answered – they were far away in intergalactic space.

This work could not have been carried out with any other telescope.

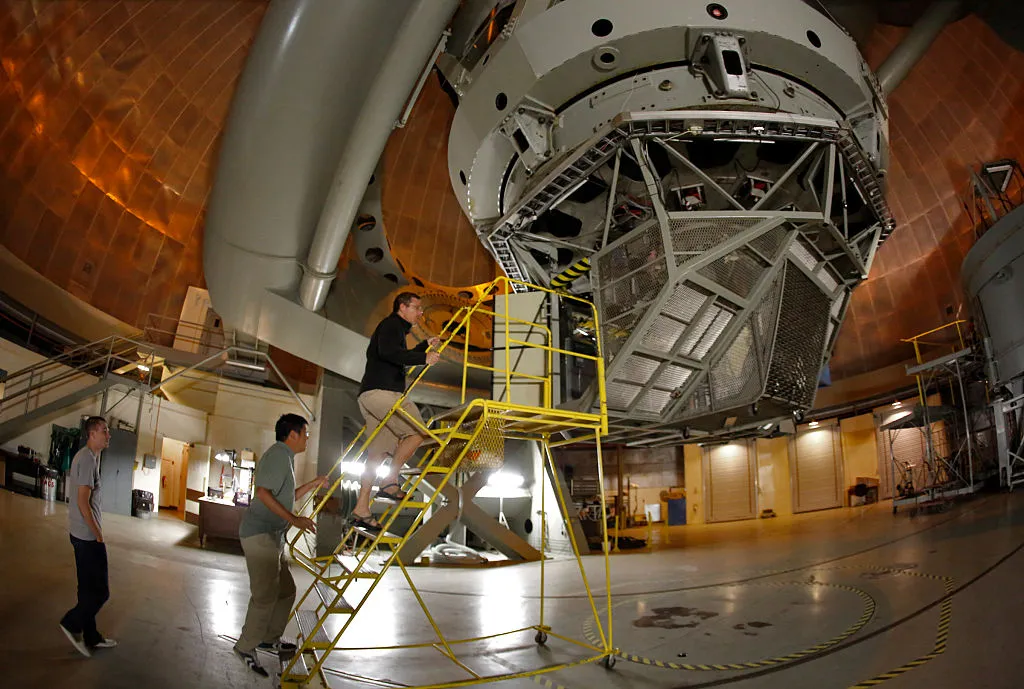

Palomar 200-inch reflector

Still Hale wasn’t satisfied. His constant call was for "more light!" and if a 100-inch, why not a 200-inch?

Again he planned and succeeded, and in 1948 the 200-inch was set up on Mount Palomar.

Sadly Hale did not live to see it completed, but it’s only right that the telescope should be named after him.

It ruled supreme for several decades and was used by Walter Baade to show that the Universe is much larger than had been thought.

There had been an excusable error in the Cepheid scale used by Hubble: the stars were twice as luminous, so twice as far away, than believed.

Again, only the 200-inch was capable of making these measurements.

Hubble Space Telescope

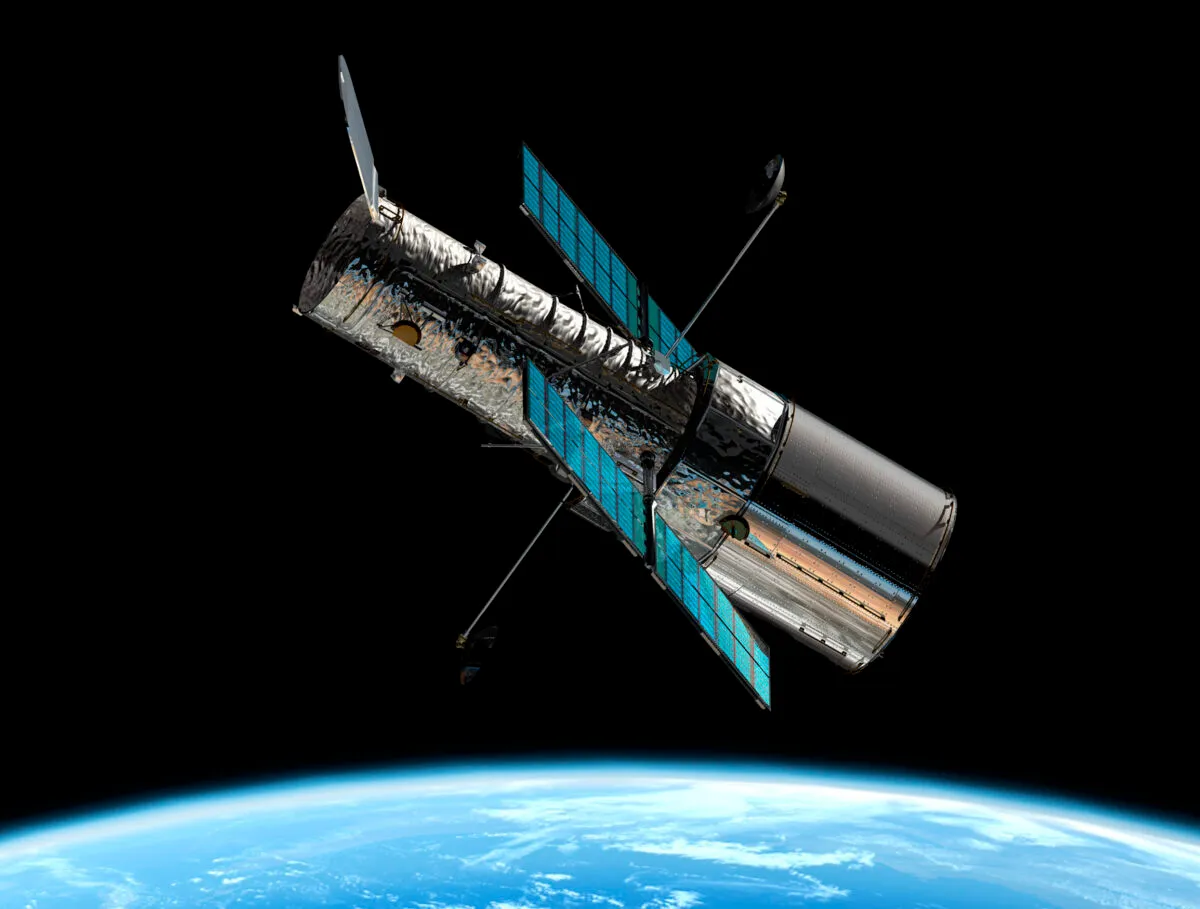

And so to 1990 and the final selection in my list of famous telescopes – the Hubble Space Telescope.

It’s ‘only’ a 94-inch but operating from above the atmosphere means it can receive wavelengths that are blocked by air.

All of us know the magnificent images it sends back, but pictures are only a part of its scientific programme.

It will not last indefinitely, but let us hope that it continues to function for a long time yet.

These, then, make up my list: Galileo, Newton, Rosse, the Hale 100-inch and 200-inch, and the Hubble.

If someone makes a list in, say, the year 2200, I wonder what theirs will be?

What are your favourites among the most famous telescopes in history? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This article originally appeared in the January 2007 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.