With the death of Sir Patrick Moore in 2012, the world lost one of its most famous and celebrated astronomers. Speculation quickly arose as to whether his home, Farthings in Selsey, might be made into a museum celebrating Patrick's life and work.

However, the property being located in a residential area and in close proximity to other homes meant planning considerations ruled this option out.

Rockstar-turned-astrophysicist Dr Brian May told BBC Sky at Night Magazine that Patrick's house would be sold, with the proceeds going to the South Downs Planetarium in Chichester, of which Patrick was a patron.

But what about the contents of the house? Patrick’s possessions included a multitude of astronomical equipment, telescopes, globes, notebooks and scrapbooks, as well as souvenirs and knickknacks picked up on his travels.

His collection of shot glasses alone stretched into the hundreds.

Read articles written by Patrick Moore:

Patrick never married, nor did he have any children or close relatives to whom he could bequeath his worldly goods.

But before he passed away, he appointed executors to oversee the distribution of his estate, including May and astronomer Dr John Mason, who helped found South Downs Planetarium.

It fell to them to decide how best to preserve Patrick’s legacy.

They worked with the Science Museum to take the majority of the collection, which is now held at its archive in Wroughton, where it will be accessible to the public.

“We initially thought it would be great to acquire the whole collection, but it became apparent that the scale of the collection wasn’t going to enable us to do that,” says Alison Boyle, curator at the museum.

“We were keen to not just capture the public face of Patrick Moore as a populariser of astronomy, but also his work as an astronomer. One of the most intriguing items was a 12.5-inch telescope named Oscar, which he used for his lunar mapping work.

"Oscar required a good deal of care and attention from our conservation team and was one of the items that most intrigued us.”

The Science Museum also acquired Patrick’s notebooks, of which there are about 70, including some 60 years of drawings, observations and a collection of astronomy-related newspaper clippings spanning decades.

Patrick also kept old draft scripts from his work on The Sky at Night, complete with notes detailing how episodes were developed during filming. These too are now safe in the museum’s archives.

“Patrick had a lot of lunar globes,” says Dr John Mason. “We made sure that all of the ones that were of interest went to the Science Museum, including the Russian globes from the late 1950s and early 60s that resulted from the Moon mapping done by Russian probes.

"Patrick was in contact with the Russians and Americans in the late 1950s and, having no political axe to grind, was seen as an impartial expert on lunar structures, features and geology, particularly the libration regions.

"This enabled the Russians to tie in the imagery of the lunar near side with the new imagery being obtained of the lunar far side.”

The items that could not be taken by the Science Museum were sold at auction by Christie’s in London’s South Kensington and Henry Adams Auctioneers in Chichester, near Patrick’s home, both at the beginning of October 2015.

Proceeds from the two sales went to the Sir Patrick Moore Heritage Trust, a charity set up to promote Patrick’s legacy.

We paid a visit to Christie’s on the day of the auction. Enthusiasm was palpable,

the auction room slowly filling throughout the morning as Patrick’s lots drew nearer.

Online bidders from around the world were in virtual attendance, with one item creating a stand-off between bidders in Texas and California – proof, as if it were needed, that Patrick’s influence was international.

“There was such a wonderful range, especially some of the globes,” says James Hyslop, head of department for science and books at Christie’s South Kensington, who oversaw the handling of the items.

“They weren’t necessarily some of the most expensive globes that we’ve ever handled, but they were so iconic, having been in the background of The Sky At Night for the last several decades.

“There were some extremely rare items, like a 19th Century globe of Mars of which there are really only a handful known. I had certainly never seen a globe of Mars by this maker before, and it was very exciting to see some of the rarities really capture collectors’ imaginations.”

Henry Adams Auctioneers handled the remainder of the estate, comprising mainly the smaller items, but also some larger pieces like one of Patrick’s xylophones.

Being so close to Patrick’s home in Selsey, the auction drew quite a crowd.

“It was a very busy day: there were lots of people so the saleroom was full,” says Andrew Swain of Henry Adams, who oversaw the auction.

“Many people were completely new to auctions, so there was a lot of explaining as to exactly how the whole process works.”

Because Henry Adams was tasked with auctioning the smaller items, Swain came up with the idea of creating memento boxes, each including a Hawaiian shirt, a pipe, a tie, a Pewter mug, a paperweight, four shot glasses and a letter opener.

These were some of the most popular items to go under the hammer on the day. But, Swain says, most interesting was the buzz throughout the busy auction room, as bidders shared anecdotes and stories of Patrick from down through the years.

“So many people had stories of the help with astronomy Patrick had given them,” he says. “He always had the time of day for everyone, and I think that’s why people liked him.”

Patrick’s passing and the subsequent handing of his estate was a source of remembrance for many people who met and knew him through the years, while others were able to gain insight into the generous and warm character for which he was famed.

Patrick’s long-term legacy, however, is in the work of the Heritage Trust and the many items preserved in the Science Museum that will serve astronomers and scientists alike for generations to come.

“There aren’t many people whose items we would acquire with the enormous recognition that Patrick Moore has, but because he had such a long life and career, this collection will be a brilliant resource,” says Boyle.

“Our hope is that it will be widely used. The point of us acquiring archives like these is that people will come and work on them and that other museums can use and borrow them.

"We are sure it will be a great resource for future generations.”

The science behind Patrick's legacy

"Patrick’s notebooks will be of major historical interest to people looking at developments in astronomy throughout the decades," says Dr John Mason of South Downs Planetarium.

"His work on the Moon, for example, began in the early 1950s at the Meudon Observatory in Paris, using their 33-inch refractor.

We have mapped the Moon in greater detail now, but in terms of putting into perspective how important it was at the time, those observations are of great interest.

Patrick’s observations span such a long period and will enable people to see how

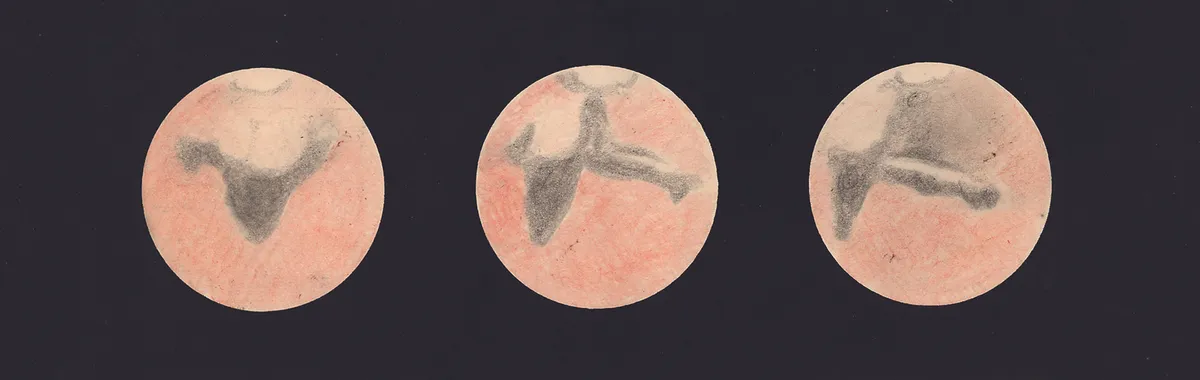

he observed, for example, the dust storms on Mars in 1971 and 1973, the South Tropical Disturbance on Jupiter or the ring plane crossings of Saturn.

All these are shown in his notebooks and are now preserved in the Science Museum.

His collection of newspaper clippings is equally invaluable. I doubt there is such an archive anywhere else of astronomy news going back so far.

For a scientific historian or even someone looking at how astronomy was viewed in the media, this will be an immensely useful resource.

We also have three of Patrick’s telescopes. The 3-inch refractor he bought in 1933 is currently on display at the South Downs Planetarium, while the other two telescopes, a 5-inch refractor and a 15.5 inch fork mounted reflector, have been dismantled and will be re-erected to inspire the next generation of young astronomers."

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Staff Writer. This article originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.