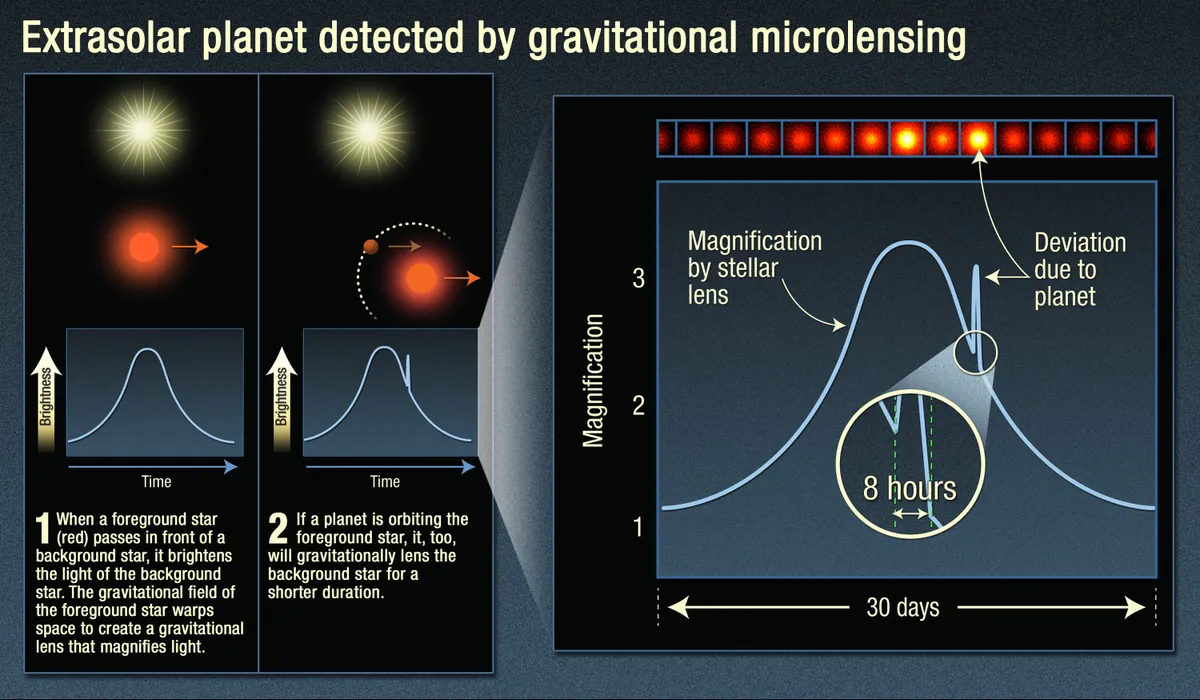

Gravitational microlensing is a method of detecting exoplanets that stems from Einstein's theory of relativity, whereby the light from a background star can be observed being warped and bent by the mass of a planet passing in front of it.

Many who are interested in space and astronomy will have heard of gravitational lensing, which works on a much grander scale and involves light from a distant galaxy being magnified by the mass of a giant galaxy cluster.

So it may seem like science fiction that astronomers can observe lensing events occurring between an exoplanet and a star.

But gravitational microlensing is fast becoming a key method of detecting planets beyond our Solar System, and is set to really take off with future missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope.

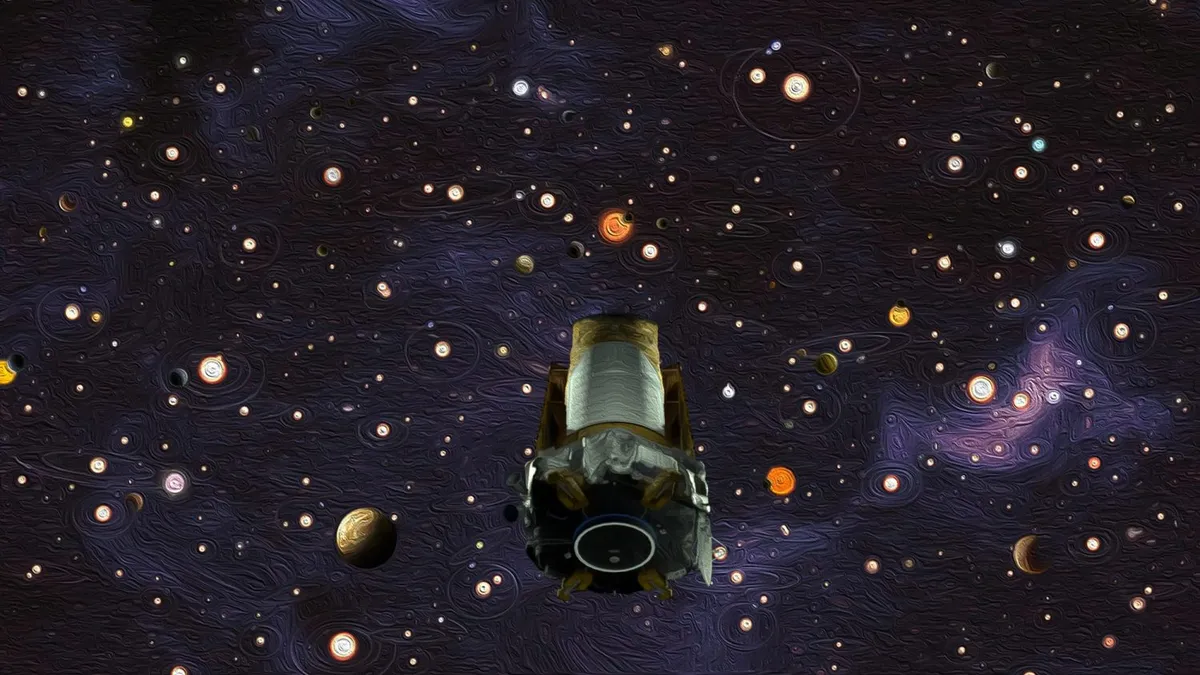

Microlensing with Kepler space telescope

Kepler space telescope retired in 2018 and is one of the most successful exoplanet-hunting missions since the first exoplanets were discovered in the 1990s.

Even though it's no longer in operation, Kepler's data is still revealing planetary candidates, including free–floating exoplanets.

Dr Iain McDonald is a Research Fellow in Astrophysics at the University of Manchester, whose field of research is in the discovery and characterisation of exoplanets.

We spoke to Dr McDonald to find out more about gravitational microlensing and how Kepler data is playing a key role in the development of the technique.

What is microlensing?

Microlensing works by waiting until an exoplanet passes in front of a background star.Einstein’s theory of relativity states that light from the background star should be bent around the planet, which acts as a lens, making the background star brighter for a short time.

This length of time depends on the mass of the lens and how fast it is moving, and for planets this is only a few hours.

Sadly, microlensing events are one-time-only, meaning we might struggle to take more data of these planetary candidates.

So far we've found 5 planetary candidates via microlensing using Kepler data.

Do we know the composition and masses of these planetary candidates?

We don’t know much about these planetary candidates, but we’re collecting together old data from Earth-bound observatories that was taken at the same time.

Differences in the time and strength of the brightening on Earth can help us separate the mass of the lens from its speed, and also prove these aren’t just normal stars that are getting brighter of their own accord.

Based on the short timescales of their brightening, though, we expect these planets to be about the same mass as Jupiter or smaller.

Unfortunately, we can’t say anything about their compositions.

Kepler was not designed to find planets using microlensing. Was it hard to find signals using its data?

Kepler was very useful because it was able to stare at a fairly large part of the sky continuously.

It was pointed at the most star-rich parts of the Galaxy, where there can be dozens of stars in every pixel.

However, many of these stars are variable and undergo brightening events of their own accord, and passing asteroids keep getting in the way.

The fact that the spacecraft kept drifting off course, because one of its stabilising wheels was broken, didn’t help either!

That meant it took four years for us to weed out the planetary candidates we wanted from the data, and be convinced that the stars weren’t getting brighter for some other reason.

Do we know if these planetary candidates have host stars?

Stars should produce their own, much stronger and longer microlensing signals, which should be visible in the light-curves too.

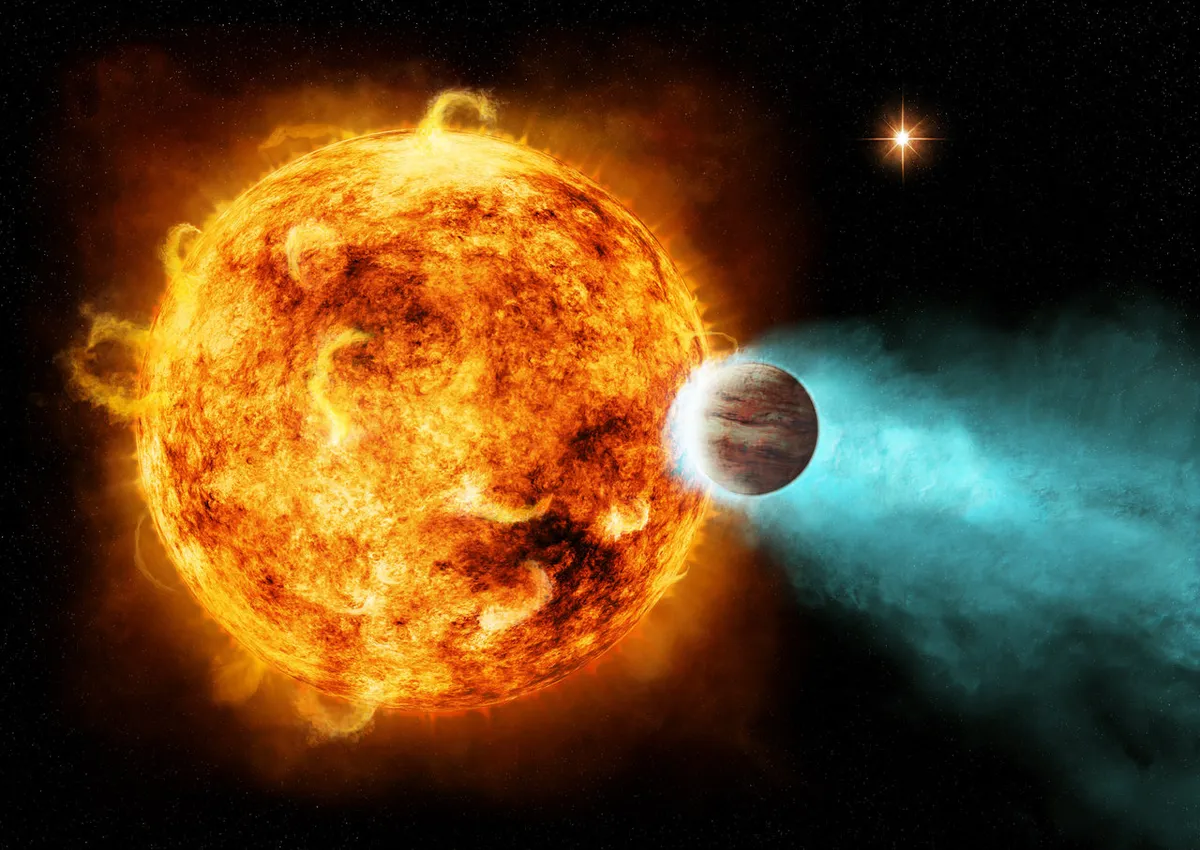

One of our planetary candidates appears to be a Jupiter-like planet going around a star.

The other four candidates we found don’t show a star-like signal to go with the planetary signal.

That could be because they are orbiting very far from their host stars, but is more likely to be because they are floating freely in space.

How did these planetary candidates come to be free-floating?

We think free-floating planets form when planetary systems are disrupted.

If one planet comes too close to another, one can be thrown towards its star (maybe making a hot Jupiter and the other one gets thrown out of the system, becoming free-floating.

By studying these free-floating planets, we can look at how stable planetary systems are.

Why use microlensing for exoplanet-hunting?

Most exoplanet-hunting techniques either find planets really close into their star (like the transit and radial-velocity methods), or very big, young planets far away from their star (the direct-imaging method).

Microlensing is really helpful for catching the planets in the middle – planets that are similar to our own Jupiter – and smaller planets much further out, including free-floating ones.

It’s even quite effective at detecting Earth-like planets.

Other methods require many years to detect such planets. Instead, microlensing relies on the blind luck of the planet passing in front of a star.