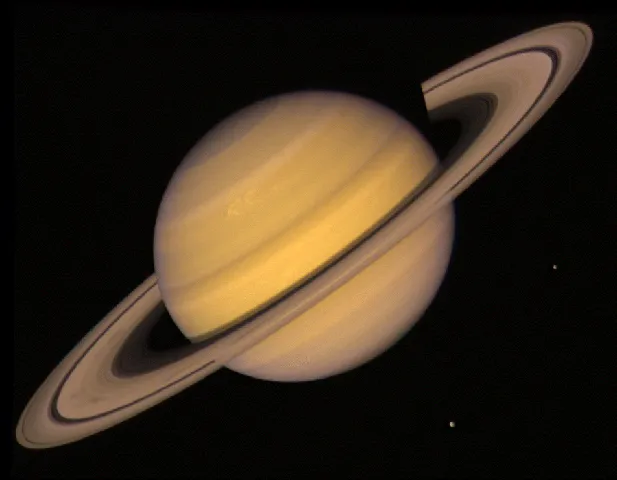

Saturn is a gas giant made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, with 274 moons orbiting it and a huge system of rings

Saturn’s rings have captivated astronomers since they were first spotted in 1610.

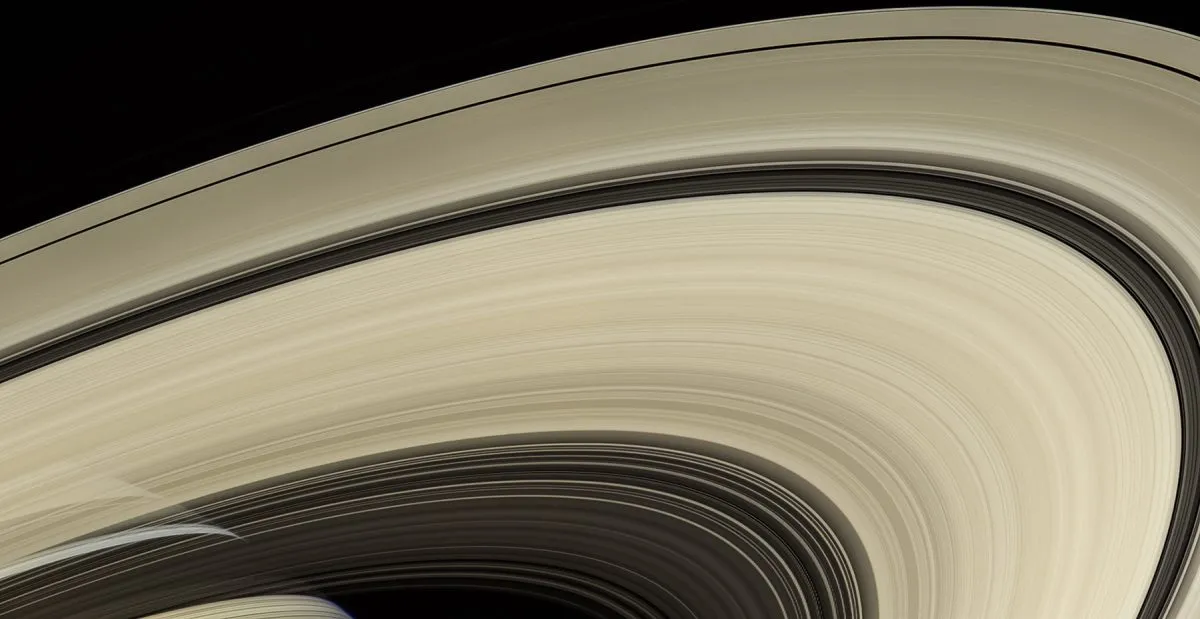

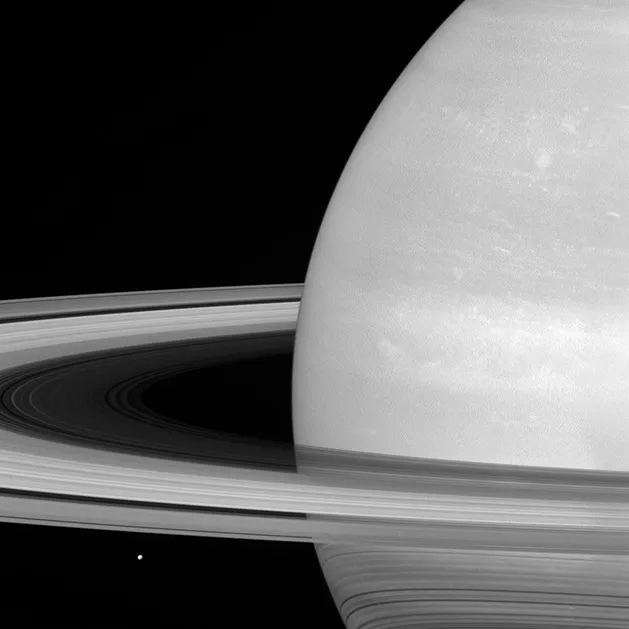

They are made up of billions of fragments of ice, ranging from the size of a grain of sand to boulders several metres across, creating a disc spanning 250,000km from side to side, but which is only 1km thick.

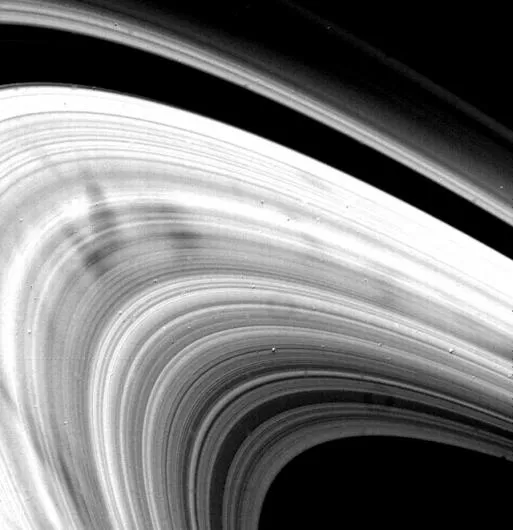

Interactions with Saturn’s moons pulls this disc into a series of rings, as well as creating beautiful wave patterns, which were captured in spectacular detail by the Cassini space probe.

No one is sure how permanent the rings are. Some studies suggest the rings are only few hundred million years old, while others suggest they could have been around for billions of years, making them as old as the planet itself.

Quick Saturn facts

- Diameter: 116,464km (9.14 times Earth), 250,000km including rings

- Mass: 568 trillion trillion kg (95 times Earth)

- Distance from the Sun: 1433.5 million km (9.58 AU)

- Length of day: 10.7 hours

- Length of year: 29.4 years

- Number of moons: 274

- Average temperature: -140ºC

- Type of planet: Gas giant

Saturn's the second-largest planet in the Solar System

Saturn has a mean radius of 58,232km (36,184mi), and an equatorial diameter of 120,500km (74,897mi). Only Jupiter is larger, with a mean radius of 69,911km (43,441mi) and an equatorial diameter of 139,820km (86,880mi)

It’s a gas giant

Like Jupiter, Saturn is mostly made of hydrogen and helium, and it has no solid surface that you could ever stand on. As a result, it has just one-eighth of Earth’s density – despite having 95 times Earth’s mass.

It’s got rings

Saturn has the most complex ring system in the Solar System. These rings are made of 99.8% water ice, with some rocky components, and the countless of millions of particles from which they’re formed range from a few micrometres (a micrometre is 0.001mm) to a few metres in diameter. The rings themselves vary in thickness from around 10m (33ft) to over 1km (3,280ft).

Galileo thought the rings were ears

As Saturn’s rings aren’t visible from Earth with the naked eye, it wasn’t until Galileo spotted them in 1610 that we had any idea they were there.

However, the resolution of Galileo’s original telescope was so poor (by modern standards) that he believed Saturn to be in three sections, with the two smaller sections sitting either side of the large, central section – like ears on a human head.

The rings weren’t so described until 1659

That’s when Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens published his Systema Saturnium, in which he first proposed that Saturn’s 'ears' were in fact a ring of material encircling the planet, as well as outlining his discovery of the planet’s largest moon, Titan.

The rings' complex structure eluded scientists for years

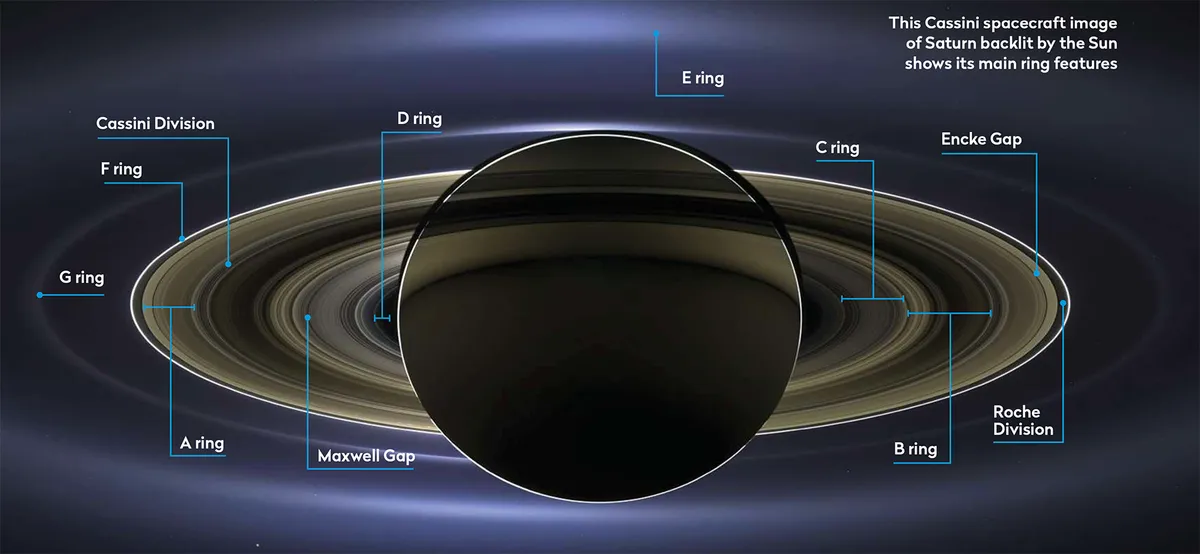

Gaileo thought Saturn had ears, Huygens thought it was surrounded by something like a life preserver… Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Domenic Cassini was the first to realise that Saturn’s ring was actually several rings. He published his findings in 1675, and the gap between the A and B rings is called the Cassini Division to this day.

But it wasn’t until 1859 that Scottish astronomer James Clerk Maxwell calculated that solid rings would be unstable, and the rings must therefore consist of millions of smaller particles, all orbiting Saturn independently.

Today, we know of at least eight rings…

The seven main rings (A-G) stretch from 6,630km to 120,700km (4,120mi to 75,000mi) above the Saturnian equator. Somewhat confusingly, they’re named in the order in which they were discovered, so the full line-up (working outwards from the planet) goes D, C, B, A, F, G and E.

There is also the fainter and more tenuous Phoebe Ring, which orbits Saturn at a much greater distance (measured in millions of kilometres).

We don’t really understand how Saturn's rings got there

Various hypotheses have been put forward regarding how Saturn came to have rings in the first place.

They could consist of matter that was ‘left over’ when Saturn itself formed, they could be the wreckage from a former moon that was pulled apart by tidal forces, or they could be debris from a collision between one or more Saturnian moons and another large, rocky body such as an asteroid or comet.

Some say they’re not really rings at all!

With more and more rings having been discovered in recent times (until the Voyager missions, we only knew about rings A, B and C), a growing number of astronomers argue that Saturn’s rings shouldn’t really be called rings at all, and that the ring system should instead be referred to as 'an annular disk with concentric local maxima and minima in density and brightness'.

It has to be said, though: ‘rings’ is a bit snappier, isn’t it?

Saturn is not as dense as Jupiter

Both planets are made mostly of hydrogen and helium, and they’re not too far apart in terms of size – yet Jupiter, despite being only a little larger, has three times Saturn’s mass.

That’s because most of Saturn’s hydrogen is in gas or liquid form – only in Saturn’s core is hydrogen found in its far denser metallic form, whereas Jupiter is composed mostly of metallic hydrogen.

It’s not even as dense as water

Saturn has a mean overall density of 0.687g/cm3, where the density of water is 1g/cm3. That makes it the least dense of all the Solar System planets (and the only one that could, in theory, float in a giant bathtub).

Saturn appears yellow when seen through a telescope

That’s because the upper layers of Saturn’s atmosphere are rich in ammonia crystals. Lower layers of the atmosphere contain large amounts of ammonium hydrosulfide and water, while traces of acetylene, ethane, propane, phosphine and methane have also been detected.

It’s named after the Roman god of wealth, abundance and agriculture

Saturn, according to Roman mythology, was the father of Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, Juno, Ceres and Vesta – all names that will be very familiar to Solar System observers.

Saturn it gives us our word for ‘Saturday’

The modern English ‘Saturday’ comes directly from the Latin ‘Saturni dies’, which means – you guessed it – ‘Saturn’s day’. Saturnalia, the most lavish of all Roman festivals, was also staged every winter in Saturn’s honour – and was the root of many European Christmas traditions.

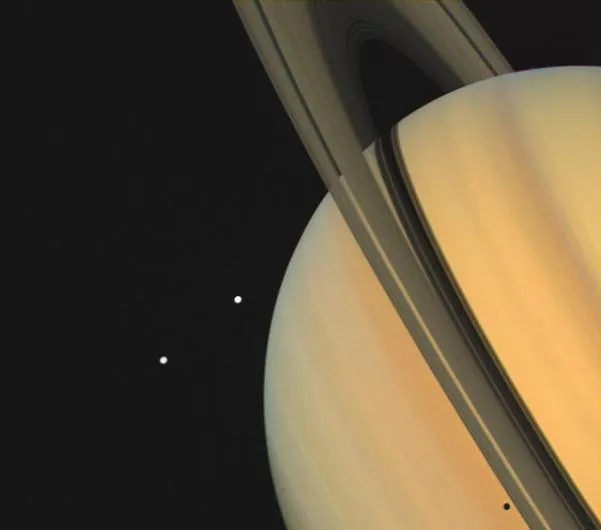

When it comes to moons, Saturn is king

Saturn’s always been able to boast more natural satellites than any other Solar System planet, but the announcement by the International Astronomy Union’s Minor Planet Center on 11 March 2025 that a further 128 moons had been confirmed pushed Saturn’s total to an incredible 274 moons, with diameters ranging from 2km (1.25mi) to 5,150km (2,300mi).

Its largest moon, Titan, is bigger than Mercury

With a mean radius of 2,575km (1,600mi), Titan is the second-largest natural satellite in the Solar System (after Jupiter’s moon Ganymede) and is larger than the planet Mercury, which has a mean radius of 2,440km (1,516mi). It’s also 50% larger by diameter than Earth’s own Moon (and 80% more massive).

Titan and Saturn’s other large moons are named after titans

Some knowledge of Greek mythology is useful here! According to legend, the 12 Titans (six male and six female) were the offspring of Gaia and Uranus (the Earth and sky, respectively) and were the 'original' gods – with Cronos (AKA Saturn) as their king.

They were later overthrown by their own offspring – the more familiar Olympian gods such as Zeus, Poseidon, Aphrodite and Hermes.

There’s water on Titan

Titan has a denser atmosphere than Earth and is the only place apart from our own planet where we can say for sure that stable bodies of liquid water exist – albeit underground.

Water on Titan is mostly either ice, or locked in a vast subsurface ocean. The surface does have rivers, lakes and seas, but these are composed of liquid methane and ethane – not H20.

There’s probably a rocky core in Saturn somewhere

As we’ve seen, Saturn is made up mostly of hydrogen and helium, with metallic hydrogen in the planet’s core, liquid hydrogen and helium making up the inner layers and gaseous hydrogen the helium in the upper/outer layers.

However, the metallic hydrogen in the core is thought to surround an inner core, made of rock and ice, with a mass around 10-20 times that of Earth.

Like Jupiter, Saturn can see some pretty major storms

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is undoubtedly the most famous ongoing storm in the Solar System, having raged since at least as far back as 1831.

Saturn can’t quite compete, but it does experience Great White Spots: these vast cyclonic storms, which (like Jupiter's Great Red Spot) make their presence felt in visual observations, occur around once every Saturnian year, and were observed in 1876, 1903, 1933, 1960 and 1990.

It has shorter days than Earth, but a longer year

Saturn takes 10.7 hours to rotate on its axis, giving it the second-shortest day in the Solar System (a day on Jupiter lasts for just 10 hours).

However, its years are much longer than ours: Saturn takes 10,756 days to make one complete orbit of the Sun, so its year lasts 29.4 Earth years.

Saturn has the second-fastest winds in the Solar System

Per data from the Voyager missions, windspeeds on Saturn can reach 500 m/s, or 1,800 km/h (1,118 mph).

That’s the fastest wind speed ever recorded anywhere – with the exception of Neptune, where winds can reach a blistering 2,000 km/h (1,200 mph).

Saturn's south pole is its warmest region

Many planets, including Earth, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, have ‘polar vortices’ – swirling masses of air that encircle their poles. However, Saturn’s south pole has the Solar System’s only known warm polar vortex.

So where polar vortices normally keep the poles cold, on Saturn, temperatures at the southern pole can reach -122°C. That might sound a bit nippy, but it’s positively balmy compared to the rest of Saturn, where the needle usually hovers around the -185°C mark.

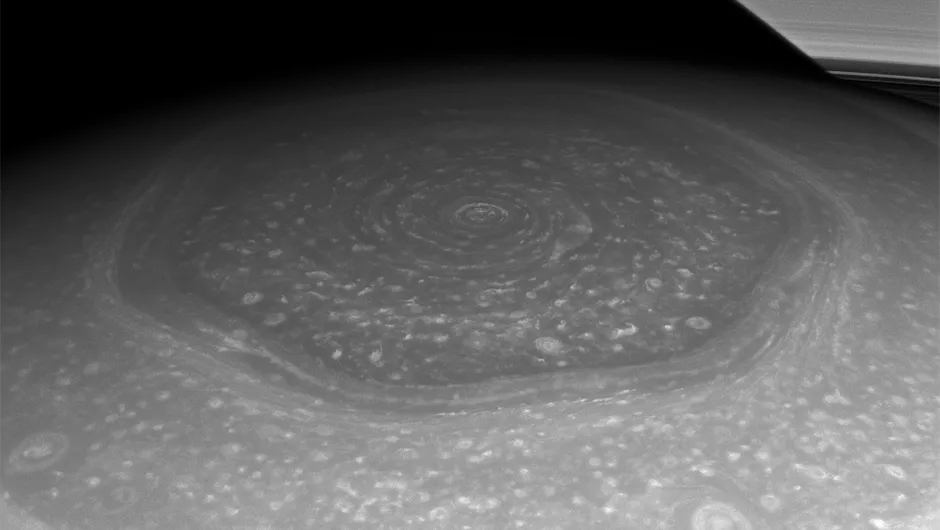

Its north pole is home to hexagonal clouds

The clouds above Saturn’s north pole have been aligned in a strikingly regular hexagonal pattern since at least 1981. Most scientists believe this to be the product of standing waves in the atmosphere, though its origins aren’t entirely clear.

Saturn's rings have an atmosphere all of their own

Saturn’s atmosphere is mostly (96.3%) molecular hydrogen, with some helium, whereas the rings’ atmosphere is made up of molecular oxygen and hydrogen, both released when UV light from the Sun hits the icy particles within them.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Sometimes they have spokes, too

At times, dark streaks appear in Saturn’s ring system (and particularly in the B Ring) that appear to radiate outwards from the planet, rather than encircling it. The precise reasons for this aren’t fully understood, but it’s believed the spokes are caused by some kind of electromagnetic phenomena (possibly lightning).

Spokes seem to be more prevalent around the time of Saturn’s equinoxes, and least common around the time of its winter and summer solstices.

One of Saturn's moons may have rings of its own

In March 2008, NASA announced that Saturn’s second-largest moon, Rhea, might have its own, very faint ring system.

That was based on fluctuations in Saturn’s magnetic field detected by the Cassini spacecraft – though follow-up visual observations failed to produce any supporting evidence.

The rings ‘disappear’ every 15 years or so

Due to the two planets’ different orbits, orbital velocities and rotational speeds, Earth passes through the plane of Saturn’s rings twice per Saturnian year. In other words, every 15 years or so we are looking at the rings edge-on, with the result that they effectively disappear from view for a little while.

This is known as a ring plane crossing event.

Titan may harbour life

With a subsurface ocean of liquid water, hydrocarbon lakes and rivers on its surface and an atmosphere that’s rich in carbon-based compounds, Titan seems to have all the chemical ingredients required for life to emerge.

If so, though, that life could have very different biochemistry from our own. It would also need to be able to survive an average surface temperature of -179°C (-290°F).

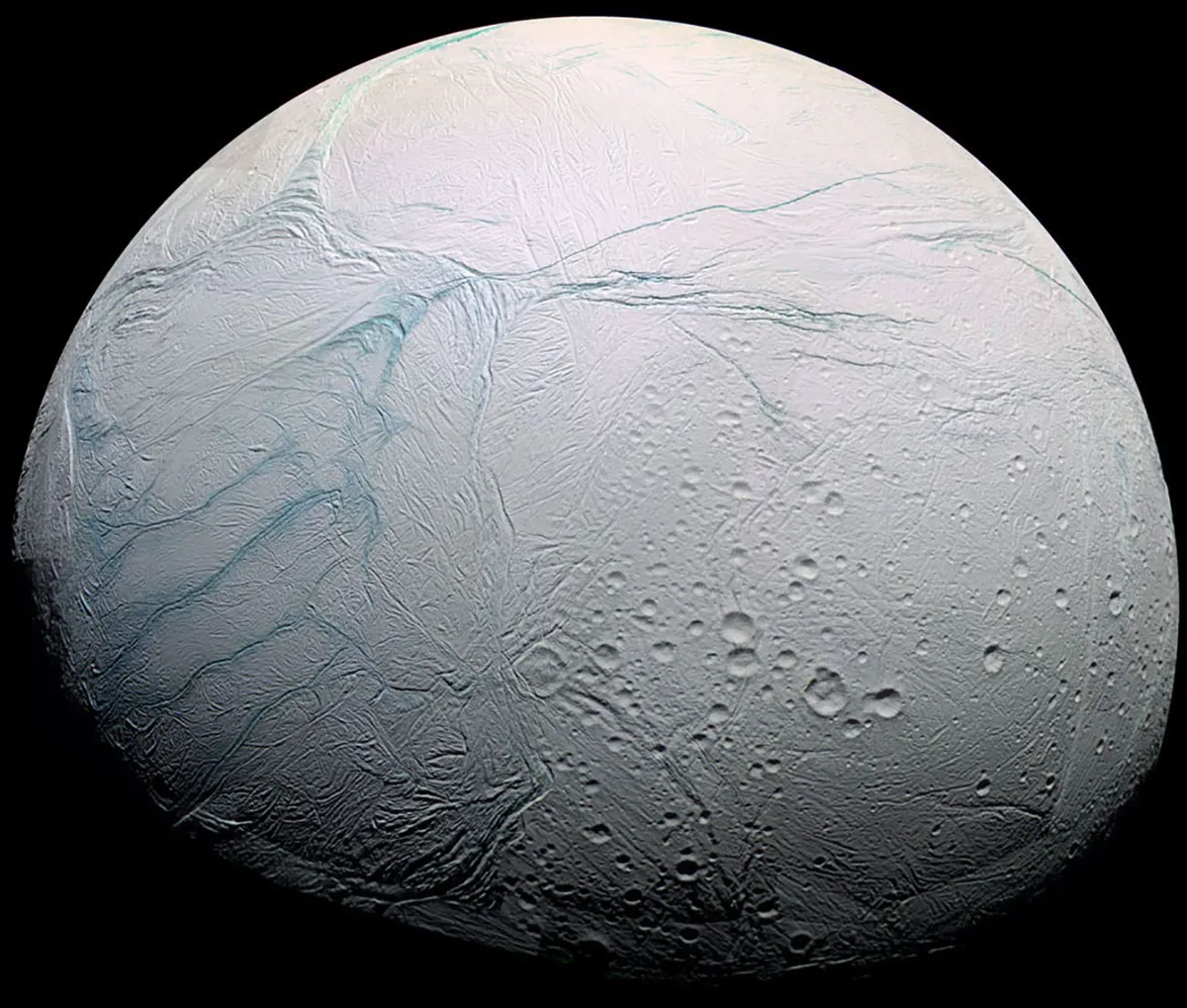

So might Enceladus

Another Saturnian moon that’s been touted as a potential host for life is Enceladus. In 2005, the Cassini probe (see below) detected geyser-like jets of water vapour and molecular hydrogen emanating from ice volcanos at the southern pole of Saturn’s sixth-largest satellite.

These plumes also contained methane, which on Earth is often produced by bioorganisms – suggesting the vents could harbour extremophile lifeforms, similar to those found around ocean floor hydrocarbon vents here on Earth.

Enceladus’s plumes feed Saturn’s E Ring

Enceladus’s orbit is contained almost entirely within the E Ring, which is the largest and most diffuse of the seven main rings.

Little surprise, then, that the E Ring has almost exactly the same chemical/mineral composition as the plumes detected coming from Enceladus by Cassini in 2005.

The first spacecraft to visit Saturn was Pioneer 11

NASA’s robotic Pioneer 11 probe launched from Cape Canaveral in April 1973 and conducted a flyby of Saturn in September 1979. Passing within 20,900km (13,000mi) of the planet’s cloud tops, it sent back low-resolution images and detected the presence of the very thin F Ring for the first time.

That was followed by Voyager 1 in 1980

Voyager 1 visited the Saturnian system in November 1980, providing higher-resolution images in which surface details could be discerned for the first time, as well as making a close flyby of Titan to learn more about the satellite’s atmosphere.

And then Voyager 2 in 1981

Due to a fault with the probe’s photographic apparatus, Voyager II didn’t prove as useful as Voyager I on the imaging front, but the mission did manage to capture some informative pictures of the various moons, and provide more details regarding the make-up of Saturn’s atmosphere.

There then followed a short interval…

After three flybys in three years, Saturn didn’t receive another visitor until July 2004, when the Cassini-Huygens mission arrived.

The Cassini spacecraft inserted itself into Saturnian orbit and then dispatched the Huygens probe to the surface of Titan.

Cassini orbited Saturn for 13 years

Between arrival in July 2004 and being deliberately destroyed in an atmospheric entry in September 2017, Cassini had detected a new ring and four new moons, conducted close fly-bys of several moons, found Titan’s lakes and Enceladus’s plumes, and sent back images of the Sun being eclipsed by Saturn. That’ll do, probe. That’ll do.

The next visitor will be Dragonfly

Greenlit in November 2024, NASA’s Dragonfly mission is scheduled to launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket in July 2028, and arrive at Titan in 2034.

Once landed, the quadcopter-like probe (the first mission of its kind) will be able to gather surface and atmospheric samples from multiple locations – some predetermined, others TBA while it’s there, based on what’s been found so far.

Saturn has helped shape the Solar System

Interactions between multiple bodies over billions of years are incredibly complex and so difficult to model accurately, but many astrophysicists believe that Uranus and Neptune first formed much closer to the Sun, before being pushed outwards by Jupiter and Saturn as they accreted ever larger volumes of gas.

NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

It may help shield us from asteroids

It has long been suggested that Earth would be struck by many more asteroids if they didn’t encounter (and get sucked in by) the enormous gravity of Jupiter en route.

One 2017 study suggested that Saturn may also operate as an 'asteroid hoover' in the same way, though other space scientists disagree.

It features in one of the first sci-fi stories ever written

Voltaire’s 1752 novella ‘Le Micromegas’ describes Earth being visited by two extraterrestrial visitors: one from a planet orbiting Sirius and the other from Saturn.

What are your favourite facts about Saturn? What did we miss? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com