The lofty position of astronomer in a royal court has afforded whoever held the position rare privileges, quite apart from the prestige and chance to mingle in higher circles.

And for some astronomers, it was also the gateway to pursuing certain personal scientific projects that, without royal funding, may never have been realised.

In the very earliest ruling courts, the science of astronomy was still merged with astrology, before the two took their separate paths.

More astronomy history:

- A guide to ancient Chinese astronomy

- A history of the Great Leviathan telescope

- What did ancient astronomers discovery about the Universe?

Predictions made by these astrologers could weigh somewhat heavily upon them.

After failing to predict a solar eclipse in 2300 BC, two Chinese astrologers attached to the emperor’s court soon found they were detached from their heads.

But with the passing of time, attitudes towards the sky changed, as did how it was interpreted.

Great astronomers in their own right such as Tycho Brahe, Galileo Galilei and William Herschel were all to be summoned by nobility.

During the latter part of the 1500s, King Frederick II of Denmark granted revered Danish astronomer Brahe an estate on the small Swedish island of Hven, and a pot full of cash to build the Uraniborg, an observatory and research establishment where Brahe set about building all manner of astronomical instruments.

But Brahe had a rather despotic relationship with the locals, and fell out of favour with Frederick’s successor to the Danish crown.

Disagreements ensued, and the party was soon over.

However, he bounced straight back by obtaining the position of Imperial Court Astronomer to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague.

Interestingly, another astronomical titan, Johannes Kepler, replaced Brahe in that position on his unexpected death in 1601.

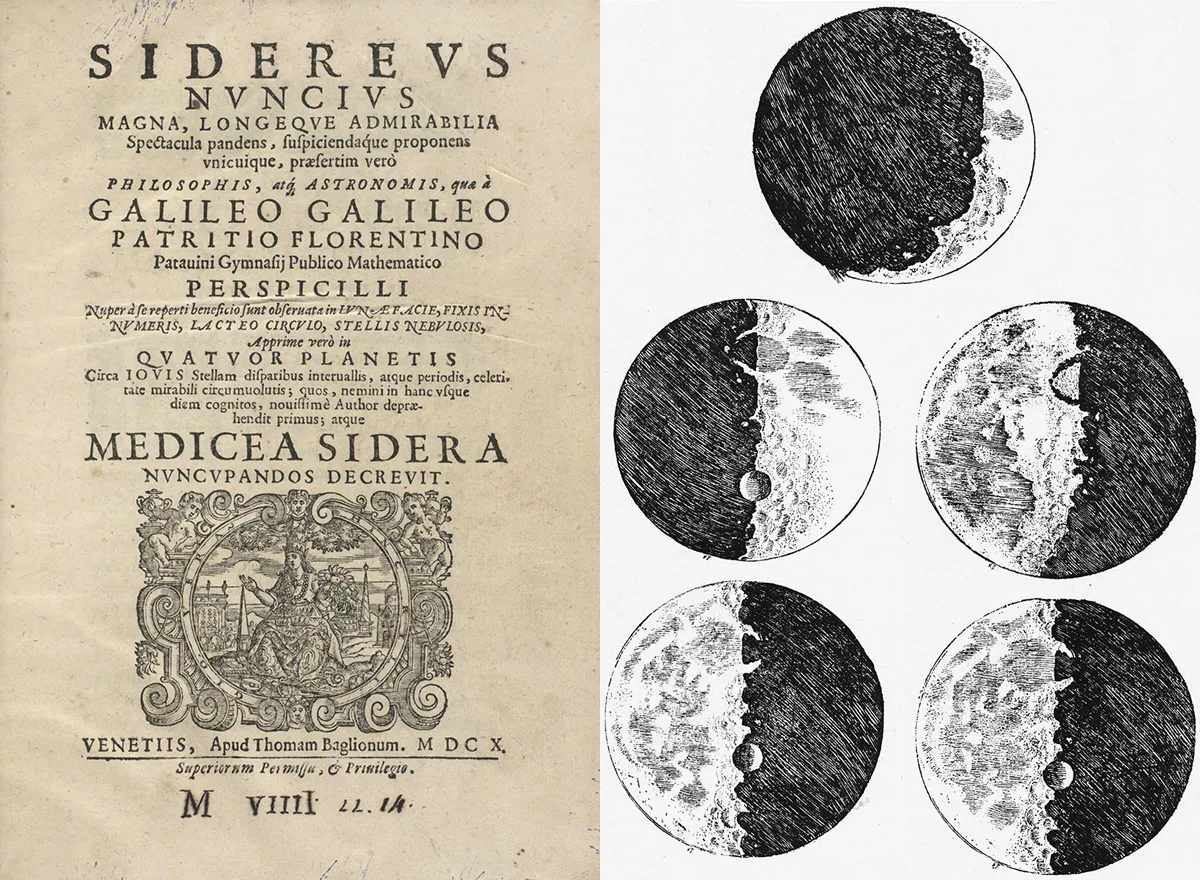

A decade later in 1610, Galileo Galilei rather shrewdly dedicated his book Sidereus Nuncius (The Sidereal Messenger) to Cosimo II de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of his native Tuscany.

This smart move saw Galileo appointed as the duke’s mathematician and philosopher, and as a courtier Galileo was duly able to live the life of a gentleman.

In later years, however, with his outspoken views on the Copernican theory, Galileo was pronounced to be suspect of heresy, and found himself condemned to a life of imprisonment.

In truth, Galileo didn’t go to clink, in fact quite the contrary: his cell was first an apartment, then a palace, then a villa.

John Flamsteed may have hoped for similar patronage when, in 1675, he compiled a report on the need for a new observatory, which resulted in the founding of Royal Greenwich Observatory.

Indeed, as its director he became the first Astronomer Royal of England. However, the cash was not forthcoming and Flamsteed had to supply all the instruments at Greenwich himself.

William Herschel was more fruitful in securing financial backing.

As a result of his discovery of Uranus in 1781, King George III bestowed upon him the title of King’s Astronomer, and then later a substantial cash advance.

This enabled Herschel to construct the giant 40-foot telescope – the world’s largest for 50 years – in Slough.

While the role of royal astronomer may not have proved productive and lucrative for all, the premise of the position, that of furthering science, has brought significant contributions to astronomy.

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.