Millions of years ago the biggest explosion in the Universe ever seen ripped through the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster. Its discovery challenges our view of such clusters.

For more on the discovery, read our story about capturing the biggest explosion in the Universe.

Dr Simona Giacintucci is an astrophysicist and a civilian radio astronomer at the US Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC.

We spoke to Dr Giacintucci to find out more about this incredible event, and how she was involved in the discovery of the biggest explosion in the Universe ever seen.

Read more: how do astronomers measure distance in space?

Why were you drawn to study the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster?

We decided to look at the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster following a paper published in 2016 by Norbert Werner et al.

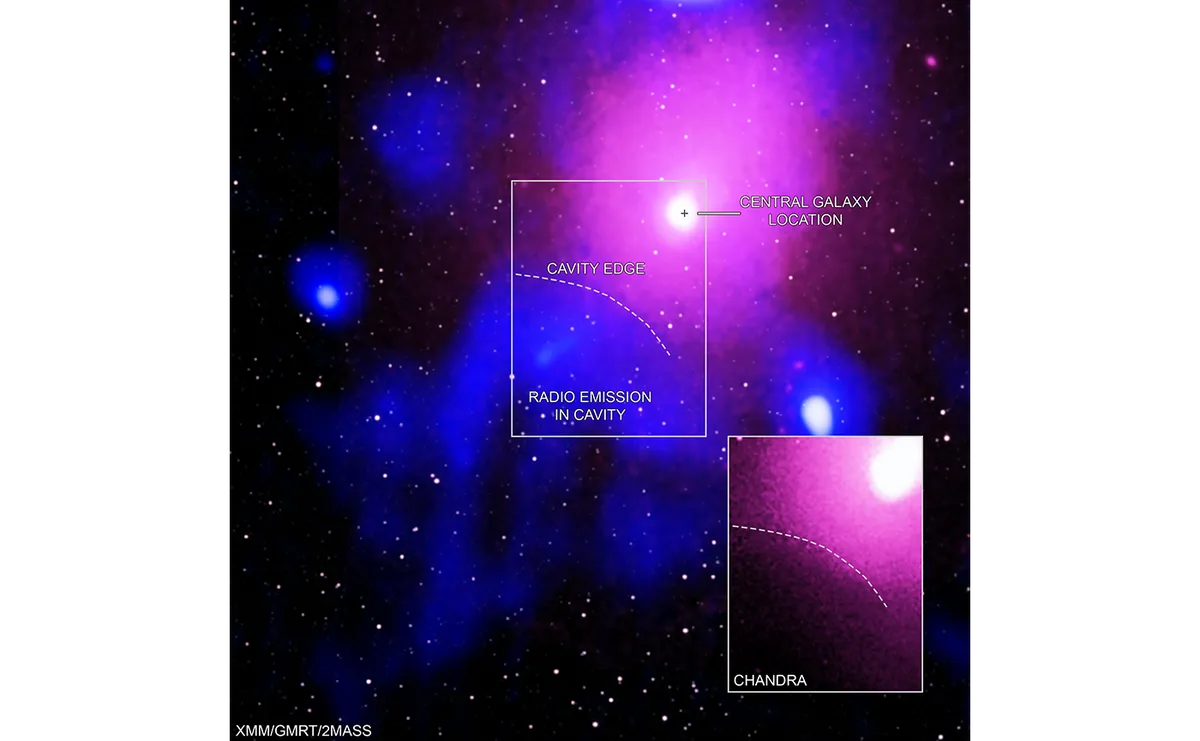

It reported a mysterious, sharp-edged curve in the X-ray image of the cluster taken using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The feature was in the hot intergalactic gas that fills the galaxy cluster, where the density of the gas dropped abruptly.

That paper briefly considered that this edge might be the wall of a giant bubble blown by a jet from the supermassive black hole in the galaxy cluster’s centre.

However, when they estimated how much energy would be required to blow such a huge bubble, they thought it was too large to be believable.

We wanted to investigate this further.

What did your investigations find?

We discovered that a large extended source of radio waves is located right next to the curved edge.

This radio emission comes from fast particles within the bubble, which we believe originated in the central supermassive black hole and were transported away by a jet.

The jet drilled through the intergalactic gas and, at some distance from the black hole, blew a huge bubble in the gas, expending a vast amount of energy and filling it with radio-emitting particles.

This tell-tale radio emission confirms a hypothesis previously considered implausible; that we are seeing a remnant of a giant eruption from the black hole.

If the hole wasn’t filled by a radio emission, it could have been some other feature related to motions of the intergalactic gas.

What did the study involve?

The patch of the sky containing Ophiuchus has been surveyed by a powerful Australian radio telescope, the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA).

We overlaid the MWA image onto the X-ray images of Ophiuchus and found a striking extended radio source right next to the X-ray edge.

We then looked at data from the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope Observatory in India, which creates sharper images.

It showed very clearly that the extended radio source fits the X-ray edge like a hand in a glove.

How powerful was this blast?

The energy released is about a billion times the energy of a powerful supernova explosion.

The blast created a huge cavity in the intergalactic gas. The diameter of this bubble is 1.5 million lightyears – it would fit 15 Milky Way galaxies in a row.

The bubble is only seen at low radio frequencies, implying the outburst happened long ago, probably a few hundred million years as the super-energetic particles lose energy after they’re ejected by the black hole.

Their radio emission started fading at high frequencies first, but remained visible at low frequencies for some time.

It looks like the black hole has no strong activity at present and all that remains from that enormous outburst is this giant radio fossil filled with aged particles.

What caused the biggest explosion in the Universe?

The black hole accretes the surrounding matter, which spirals in and forms a very hot disc.

Just before it’s swallowed by the black hole, some of the matter from the disc is redirected away from the black hole as jets that travel almost at the speed of light.

Occasionally, something big falls onto the black hole – like a big cloud of the intergalactic gas, or even a galaxy – and this causes a huge spike in the jet power.

We think this is what happened in Ophiuchus.

What are the implications of your study?

This discovery challenges our understanding of galaxy clusters. We used to think clusters are so big and massive that they are governed only by gravity.

The enormous fossil of an explosion we’ve found is much bigger than anything we’ve expected – not insignificant for the cluster’s overall energy output.

If such ‘dinosaurs’ turn up in other clusters then we’ll have to rethink a lot of things about the physics of galaxy clusters and how they are used in studies of the Universe.

This interview originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.