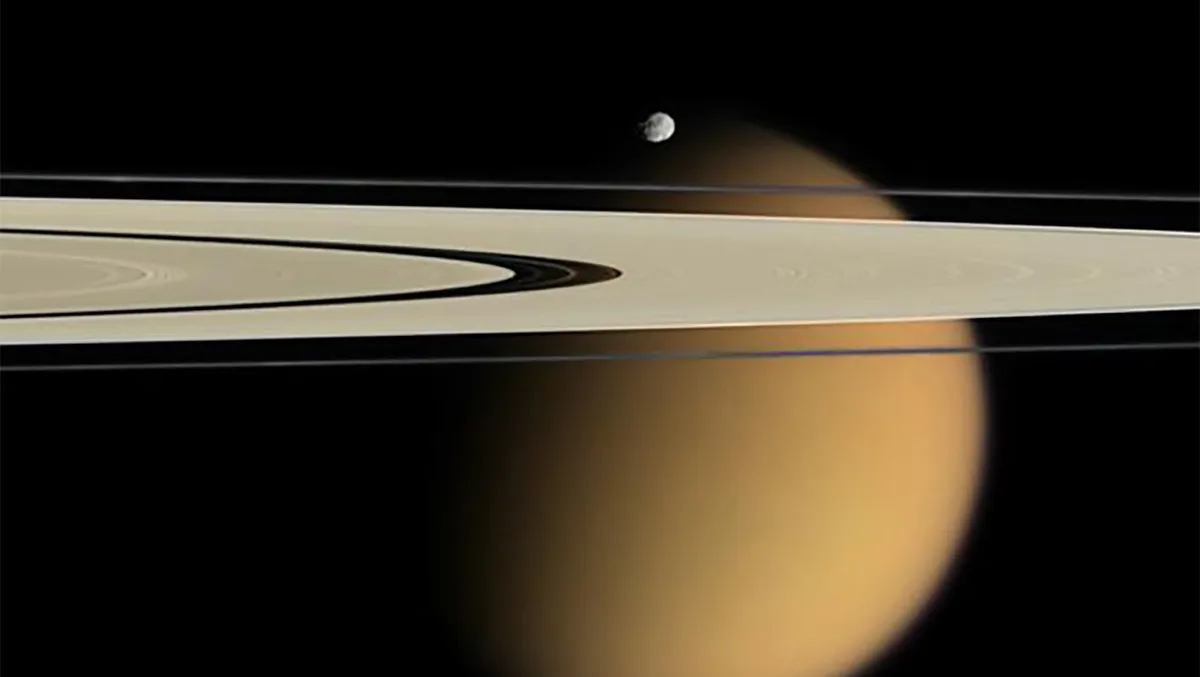

One of the largest moons in the Solar System, Titan’s even bigger than the planet Mercury. But what determines whether a gas giant gets a family of sizeable moons or a single jumbo satellite?

Gas giant planets in our Solar System, Jupiter and Saturn are pretty similar to each other. They have similar compositions and are both around 100 times more massive than Earth, and so very much in a class of their own even compared to the ice giants Uranus and Neptune.

When it comes to their moons, however, the Jupiter and Saturn systems are wildly different from each other.

Both planets have around 80 moons each, but the mass distribution amongst that number is very different.

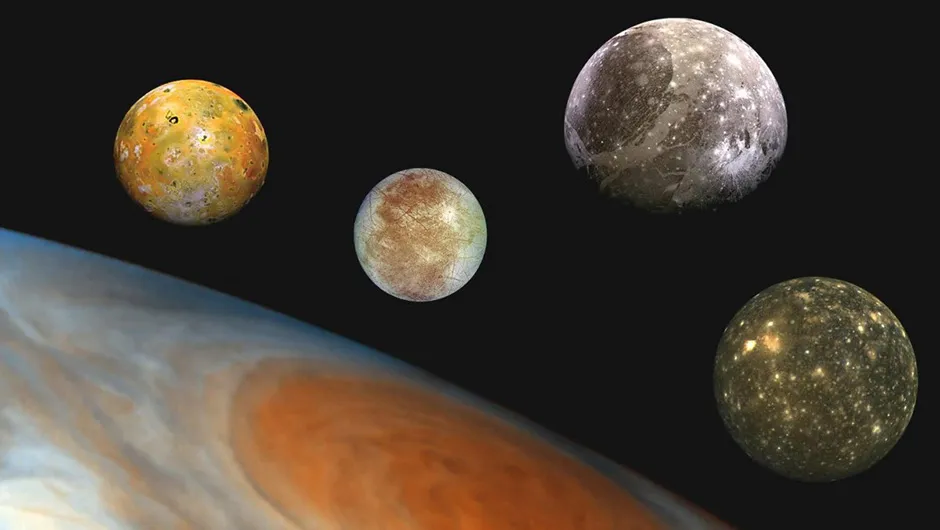

Jupiter has the 4 large Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – all the same order of magnitude in terms of size, whereas Saturn has the single giant moon, Titan.

Some moons – like Neptune’s Triton, or Phoebe around Saturn – are captured objects, but the majority of satellites around the giants are believed to be born in circumplanetary discs.

These arise when an infant star is creating a new planetary system from the large disc of gas and dust swirling around it.

Embedded within this are smaller whirlpools around the forming gas giant planets – circumplanetary discs.

Large moons coalescing in this dusty skirt of material tend to spiral in towards the planet as they experience drag from their interaction with the surrounding gas and dust: they are at danger of diving all the way down into the gas giant and becoming destroyed.

So what seems most likely is that a giant planet ends up with either no large moons, or a system of several large moons, like the Galilean satellites, that were all saved because the circumplanetary disc was dissipated quickly enough after formation.

Finishing with just a single large moon, however, seems much more difficult and leads to the question of how Titan formed.

Yuri Fujii and Masahiro Ogihara, at the Department of Physics, Nagoya University, and National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, respectively, think they’ve found the answer.

As the orbital migration of moons depends on key factors like the density and temperature of dust particles in the circumplanetary disc at different distances out from the planet, they’ve modelled different systems to study what the configuration of moons ends up like as the disc disperses.

How many moons survive, of what size, and at what orbital distance from the central planet?

Their simulations showed, as had been expected, that large moons like Titan mostly lose orbital energy in the dusty disc and spiral in towards the planet to be devoured.

For particular combinations of moon mass and orbital radius, however, the overall balance of forces causes the moon to instead drift slowly outwards, or even hover at the same orbital distance; these are like safe patches, and a single giant moon is able to survive destruction.

What appears to have happened with Saturn is that several inner moons may have spiralled all the way in to be destroyed, but Titan formed in an outer orbit and migrated inwards until it settled in one of these safe patches.

Once the disc dissipated, any further migration ceased and Titan has stayed put ever since.

This article originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.Prof Lewis Dartnell is an astrobiologist at the University of Westminster.

Lewis was reading Formation of single-moon systems around gas giants by Yuri I Fujii and Mashahiro Ogihara. Read it online at https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.05052.