Dr Farzana Meru is an assistant professor and Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow at the University of Warwick. Her research is on the formation of planets, and she uses a variety of techniques to investigate how they grow.

BBC Sky at Night Magazine spoke to Dr Meru to find out more about planet formation.

Where do planets form?

Planets form in discs made of gas and dust — called protoplanetary discs — that swirl around their central star.

4.6 billion years ago our own Sun would have had one of these discs, which went on to form the planets.

How does the formation process work?

There are two ways we think planets form. The main way is via core accretion — where the dust in a disc collides, sticks together and grows to form a planetary core.

As this core becomes more massive, its gravity pulls more dust and gas onto it, forming a terrestrial planet. If the core can gain sufficient mass it starts rapidly gathering gas, forming a gas giant planet.

Another way in which planets can form is through gravitational instability.

In the early stages of a protoplanetary disc’s life, it is so massive that its own gravity causes spirals to form — similar to the spiral features in a galaxy.

If the gravity in the spirals is strong enough, they can become unstable and break apart into gas balls.

Eventually dust collects in the middle of these gas balls and they grow to form giant planets.

What do observed images of protoplanetary discs tell us?

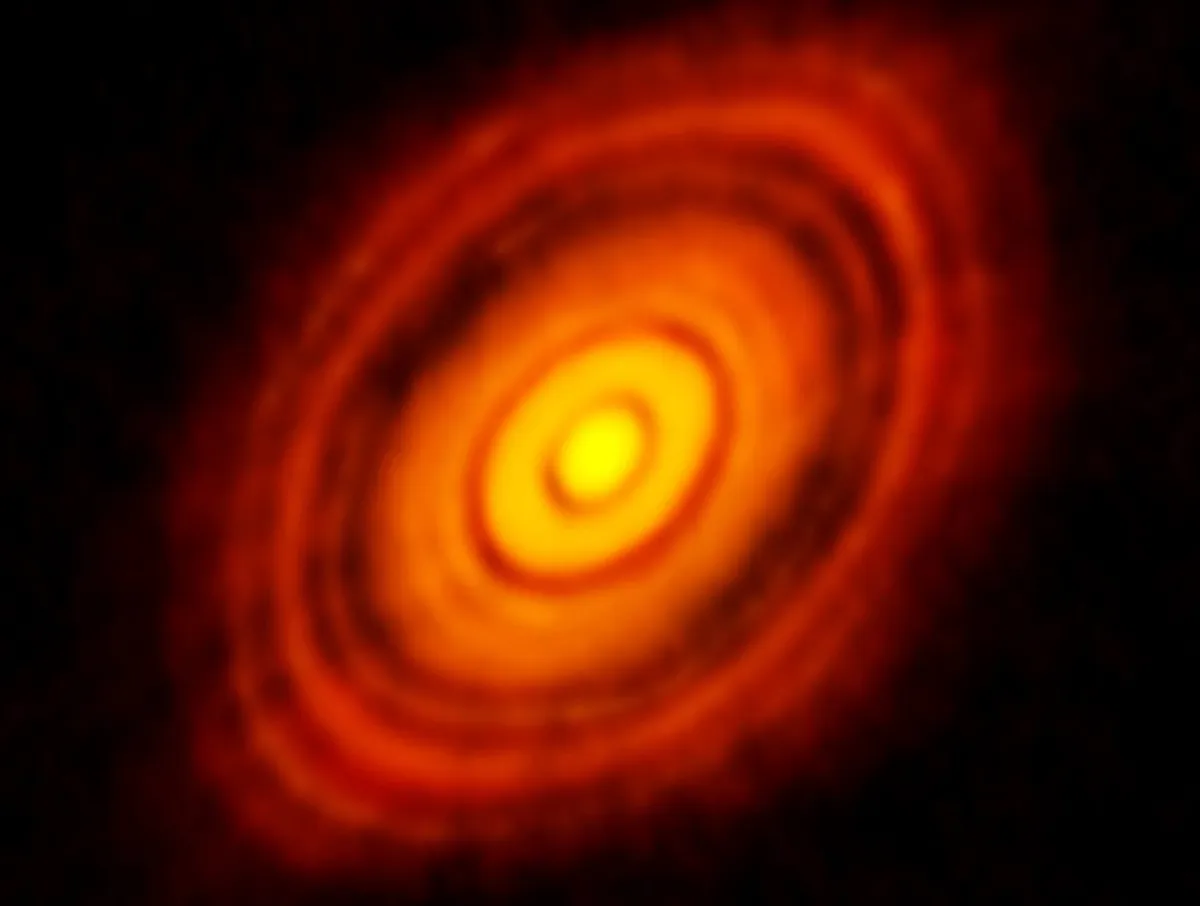

We are living in a revolutionary era where powerful state-of-the-art telescopes are able to take high resolution images of protoplanetary discs, showing features such as rings, gaps and spirals.

These features give us clues about how protoplanetary discs evolve and how planets form.

Some of these features may be created by planets already within the disc.

We can use complex computer models and theoretical knowledge to determine if planets can exist in these discs, and even try to constrain the properties of those planets such as their mass and orbital distance.

Observations give us snapshots of what discs look like, but combined with powerful computer simulations, we have an incredible insight into how planets form and evolve.

Can we directly observe planets forming?

We are just beginning to do this. Recently astronomers have indirectly detected a planet in the disc around the star CI Tauri using a technique which measures the planet’s gravitational pull on its host star.

But the first direct image of a planet in a disc came last year when astronomers took an image of a forming planet around the star PDS 70.

With new technological developments we hope we can detect more newborn planets.

Is our Solar System unique?

We have discovered over 4,000 extra-solar planets outside our own Solar System, and there’s a huge amount of diversity among them.

Based on the discoveries from the Kepler space mission, the most common type of planet out there is one that we do not have in our Solar System: a Super-Earth – approximately 10 times Earth’s mass.

In fact, current findings seem to suggest that our Solar System is not a typical planetary system.

This interview first appeared in the November 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.