The planet Uranus was discovered on 13 March 1781 by astronomer William Herschel.

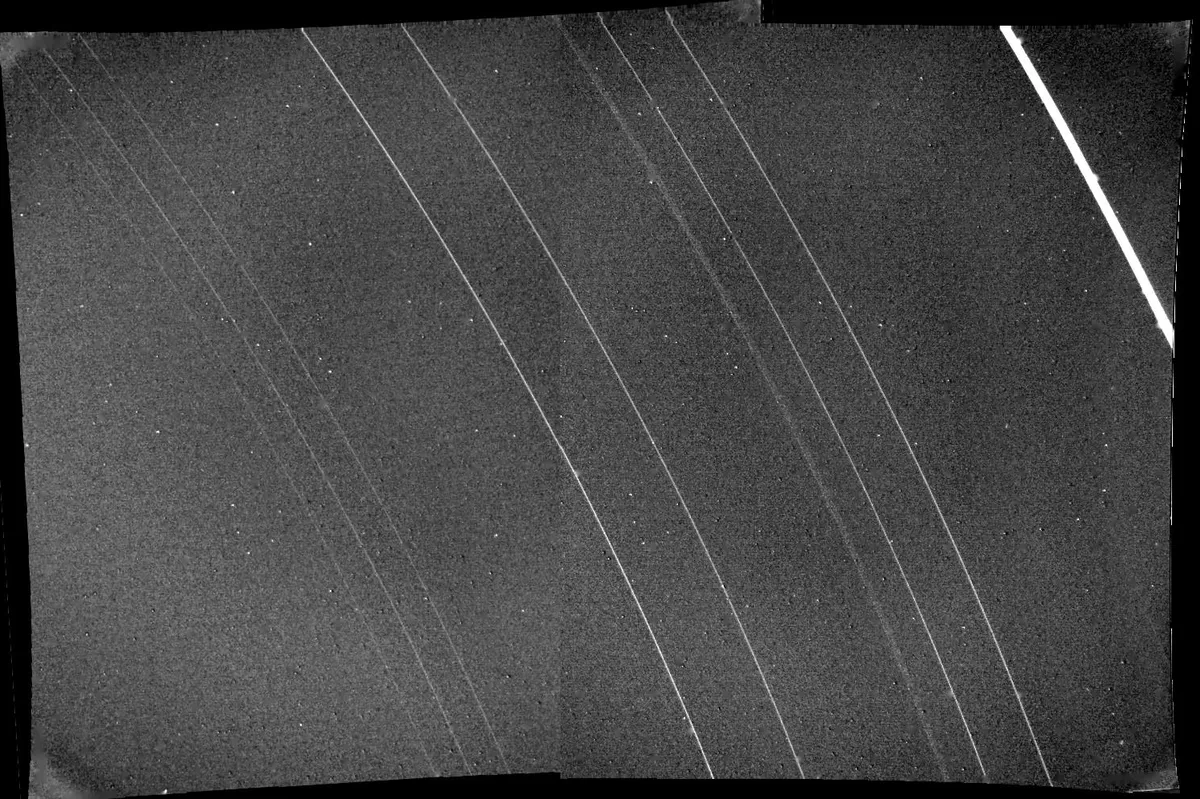

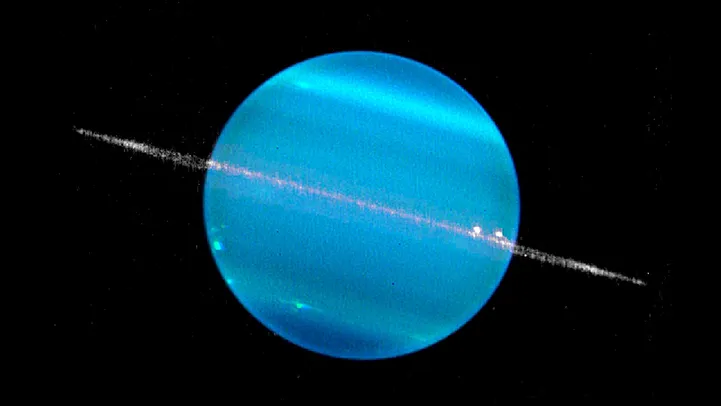

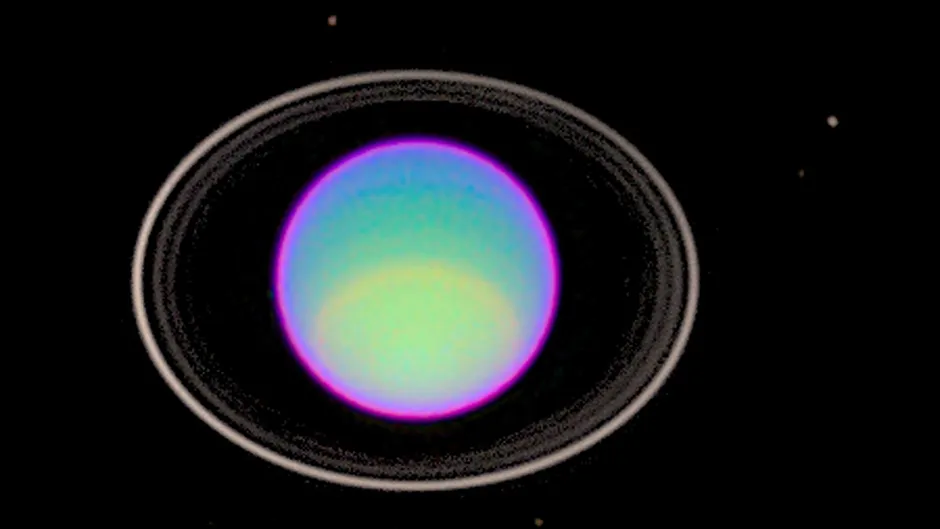

On 24 January 1986 we got our closest views of the ice giant to date, thanks to the Voyager 2 space probe.

Read more

Passing the planet at a distance of just 50,600 miles and spending 6 hours within the Uranian system, Voyager is so far the only craft ever to visit the seventh planet from the Sun.

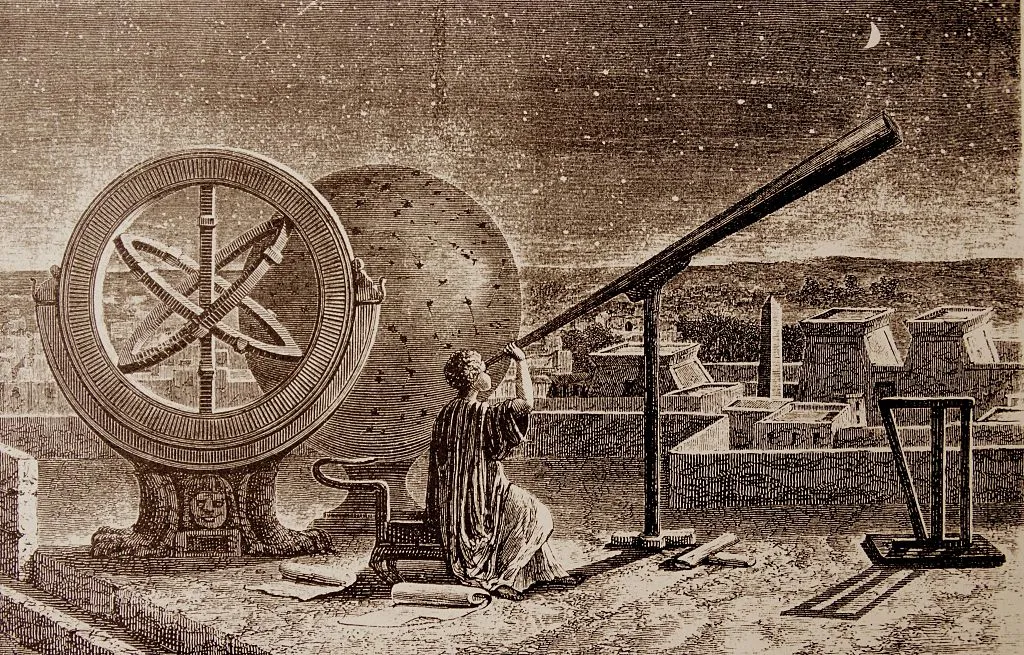

To the ancients only six planets and one moon were known to belong to the Sun's family, and this was to be the way of things for thousands of years.

Until, by complete accident in 1781, Sir William Herschel was to make a discovery that expanded humanity’s knowledge of Solar System.

Who was William Herschel?

Born Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel in Hanover, Germany, in 1738, Herschel came to England in 1757, eventually settling in the city of Bath, Somerset, becoming an organist at the fashionable spa town’s Octagon Chapel and the resort’s Director of Public Concerts.

As well as music his other passion was astronomy, and he mastered the skill of making his own reflecting telescopes.

On the night of 13 March 1781, using his own 6.2-inch telescope in the back garden of his house at 19 New King Street (now the Herschel Museum of Astronomy) , he noted an interesting object near to the star Zeta Tauri.

At the time Herschel was cataloguing all stars down to stellar magnitude +8.0 in brightness and in his astronomical logbook he wrote: "In the quartile near Zeta Tauri...either (a) Nebulous star or perhaps a comet."

Four days later, on 17 March 1781, he turned his telescope towards the same area of sky and instantly noted that the object had moved a small distance relative to the fixed stars in his field of view.

Herschel noted in his logbook: "I looked for the comet or Nebulous star and found it was a comet, for it has changed its place."

Herschel announced his discovery to the Royal Society, still maintaining that it was a comet, but did also imply the possibility that it could be a planet.

Though interesting in the potential for appearing as spectacular objects, comets were by no means a rare event in the late 18th century – just like today – and Herschel seemed rather underwhelmed by his discovery at the time.

Indeed, his first paper on the object was entitled ‘An account of a comet’.

Astronomers began working on an orbit for this new object and very quickly realised that this was no comet that Herschel had seen.

Instead, they had something special on their hands.

Herschel duly notified the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, who rather unenthusiastically replied to him on 23 April 1781: "I don’t know what to call it. It is as likely to be a regular planet moving in an orbit nearly circular to the Sun as a comet moving in a very eccentric ellipse.

"I have not yet seen any coma or tail to it."

The first astronomer to come up with an orbit was the Finnish-Swede Anders Johan Lexell. His conclusion was that the orbit was virtually circular and more planetary than cometary in nature.

German astronomer Johann Elert Bode then began investigating the object seriously and, after an extensive search through old sky charts, discovered the object had already been recorded several times before in the past and had been documented as a normal star.

This included no fewer than six observations by John Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal between 1690 and 1715, who not only recorded it but also numbered it 34 Tauri in his own catalogue.

Noted French astronomer Pierre Charles Le Monnier had also documented it no fewer than a dozen times between 1750 and 1769.

And with these previous sightings it now became clear to Bode that the object Herschel had observed was in fact a new planet within the Solar System.

A distant and slow moving one at that, taking some 84 years to complete a single orbit of the Sun.

Who first observed Uranus?

The first recording of the planet may actually belong to Hipparchos, who in 128 BC may have included it in his star catalogue, which is unsurprising given the planet hovers at the limit of naked-eye visibility at magnitude +5.7.

Indeed, without the hindrance of light pollution in ages past it is perhaps remarkable that it took until 1781 for a conclusive discovery to be made.

It has taken even longer for astronomers to discover Uranus's moons.

How Uranus got its name

Bode was also the first to suggest Uranus for the name of the new planet. Herschel had named Georgium Sidus (the Georgian Star) in honour of the monarch of the time, George III.

However this name was not widely accepted outside Britain and, as Bode’s name fitted with the usual procedure of naming objects, Uranus was duly accepted as the official designation.

It is interesting to note however that in Britain the name Uranus was not accepted until 1850, and it remained known as Georgium Sidus from 1783 until then.

How to pronounce Uranus

Given the propensity for jokes to be made any time anyone happens to mention the planet Uranus – particularly when discussing Uranus's smelly gas, its heat or the presence of methane in its composition – many academics and astronomers have taken to pronouncing it with the stress on the first syllable, so that it sounds like YOOR-inuss.

Whether or not this actually helps avoid the inevitable stifled sniggers any time the planet's name is mentioned, however, is debatable.