Astronomers have spent many years wondering about what the first stars were like, and what will happen to the last ones several trillion years from now, coming up with many hypothetical celestial objects in the process.

Some are real stellar oddballs, and might be considered the weirdest stars in the Universe.

There have been several stars that were thought to exist, only to later be proven impossible as we came to better understand the laws that govern the Universe. Others turn out to be something else entirely.

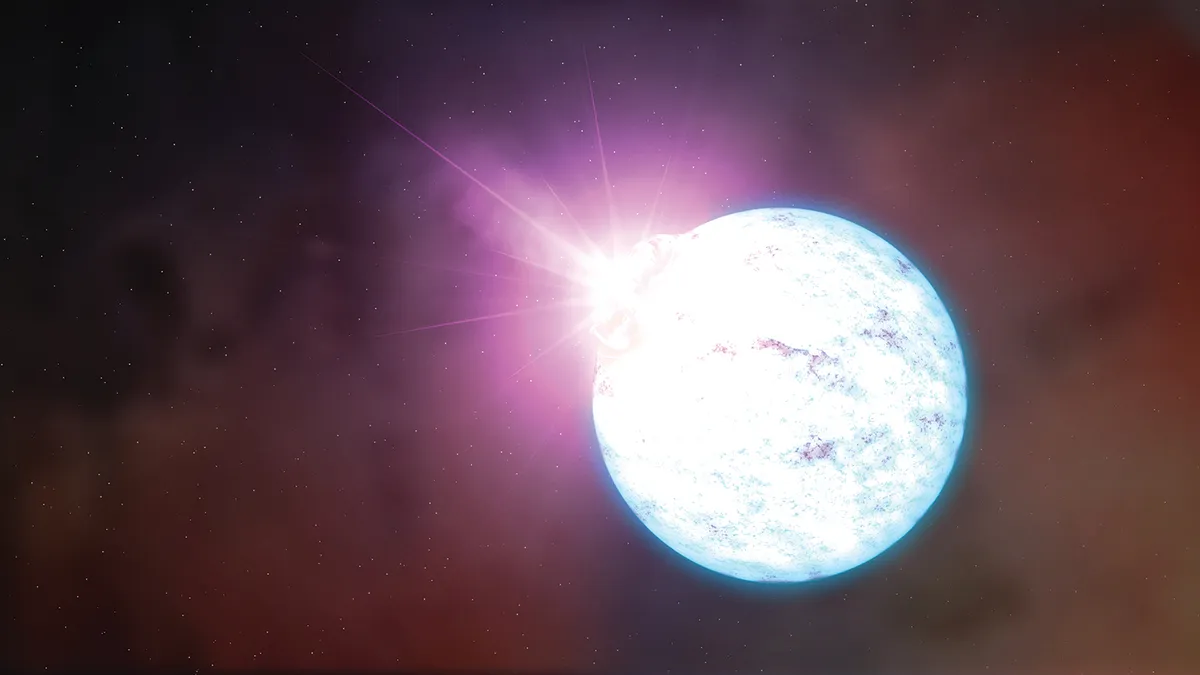

In 1975, two physicists suggested a new type of hybrid star, a red giant with a neutron star hidden inside it, which they named a Thorne-Zytkow Object ( an artist's impression of which is pictured at the top of this page).

More strange space science:

In June 2014, nearly 40 years later, a group of scientists researching red giants using the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile discovered what they believe might be one of these strange stellar bodies.

In 1784, it was suggested that some stars could be so massive that they would have enough gravity to stop light from escaping.

It wasn’t until Einstein proposed the general theory of relativity in 1915 that the idea of such stars was superseded by black holes.

With more powerful telescopes and new technologies it might one day be possible to find some of these exotic stars, which, perhaps, really do exist. Here are some of the prime candidates.

Population III stars

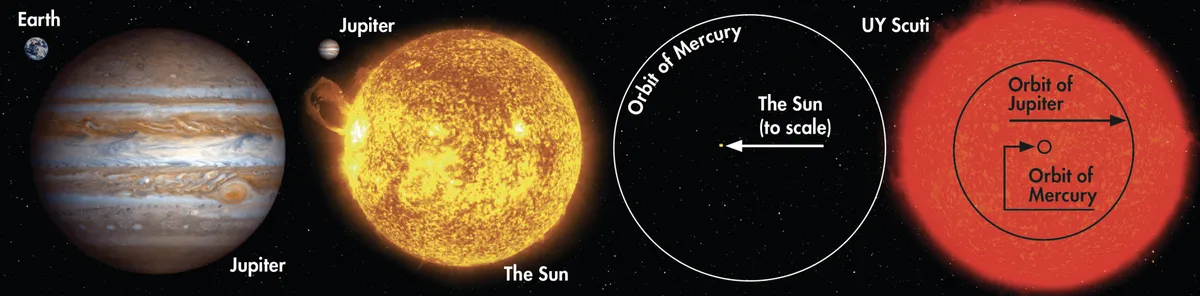

The early Universe was almost devoid of heavy elements, meaning the first stars would have been pretty much completely made of hydrogen and helium.

These ‘Population III’ stars would have been several hundred times the mass of the Sun, meaning that they would have quickly burned through their fuel and gone supernova.

As this process would have filled the surrounding space with heavier elements, it is unlikely that any stars of this type exist in the local Universe.

However, gamma-ray burst GRB 130925A – observed in 2013 – is thought to be from the collapse of one of these stars, the light of which is only just reaching us.

Dark stars

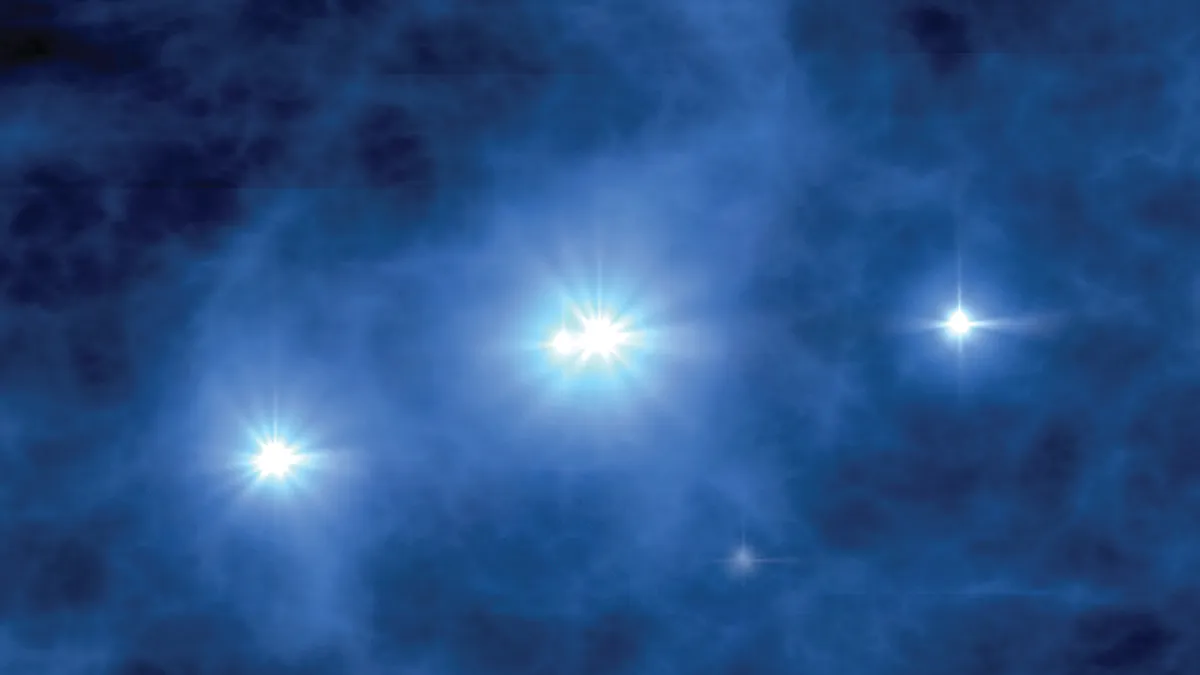

Another of the Universe’s earliest stars may have been a more unusual breed. As galaxies began to form, dark matter congregated at their centres, and stars born in the region may have been created with dark matter making up as much as 10% of their mass.

This extra matter would have allowed the stars to grow to several million times the mass of the Sun, and a billion times brighter, but they would have been short lived.

Soon the dark matter fuel would have run out, collapsing the star. This may even be how supermassive black holes form.

Blitzars

Even in the current Universe there are stars waiting to be found, among them the blitzar. Dying stars only go supernova and collapse into black holes when they are above a certain mass; otherwise they will form a neutron star.

Blitzars are neutron stars with masses above the supernova threshold, but held together by a rapid spin speed.

Over time, the spinning slows and eventually the star will collapse into a black hole, releasing an incredible amount of energy.

Quark Stars

There is another hypothetical star bridging the gap between a neutron star and a black hole. If the mass of a neutron star is not enough to collapse into a black hole, but is massive enough to break down the neutrons into their component quarks, it could form a quark star.

In this state the quarks would only be able to exist under extreme pressures and temperatures. If, however, the quarks could transform into the more massive ‘strange quarks’, they would be much more stable.

Over the years several potential candidates for these quark stars have been found, but as yet none has been confirmed.

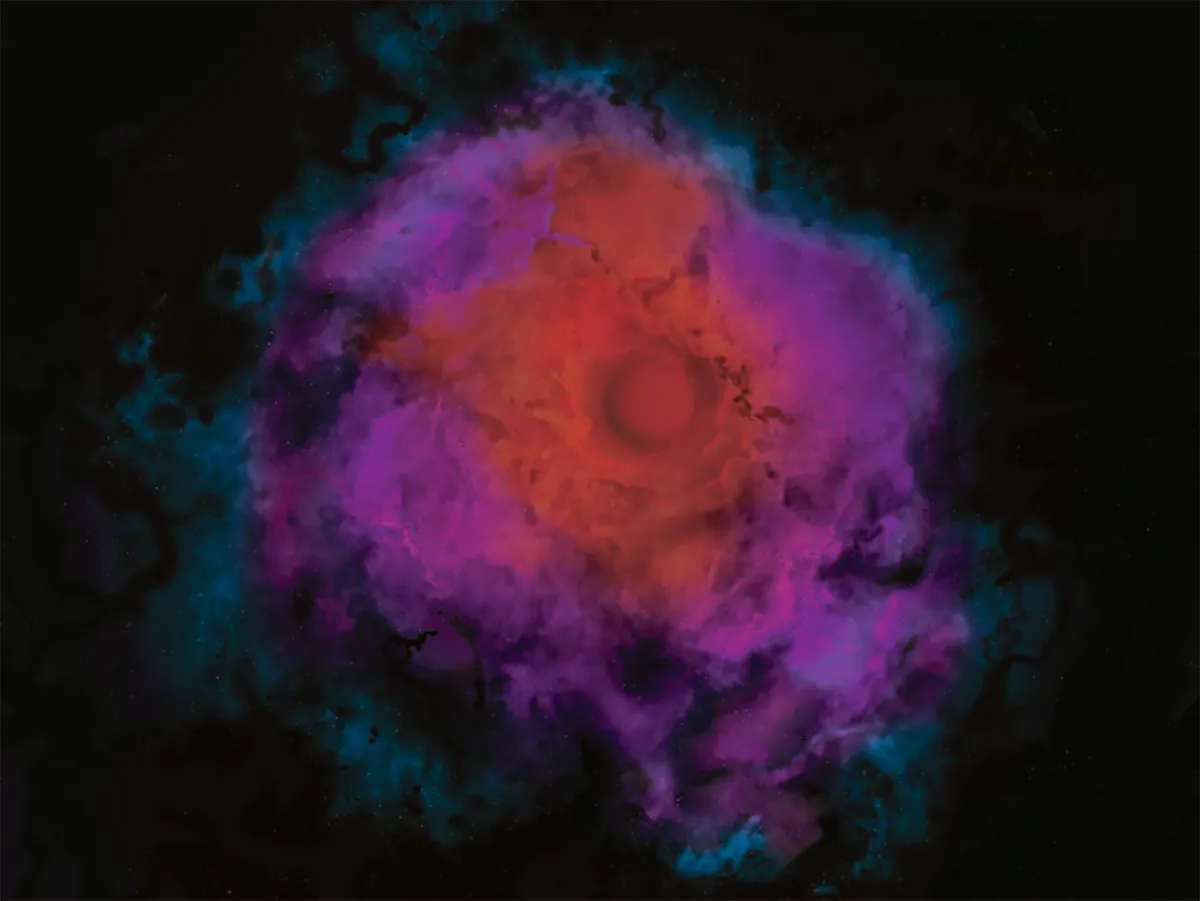

Black dwarfs

The ultimate fate of our own Sun is a question that many astronomers have tried to answer. In five billion years time the Sun will have burned itself out, shrinking to a white dwarf, as will many other stars like it.

Instead of generating its energy through fusion, all its light will come from its intense heat radiating away. Over time, the star will dim and cool, until all that is left behind is a cold black dwarf.

How long this will take is not very certain, but even the shortest estimate states that it will take over a quadrillion (one thousand million million) years to reach this phase, so it will be a while until anyone can observe one.

This article appeared in the October 2014 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.