The outermost of Saturn’s major satellites, Iapetus, is an enigma – and has been so ever since its discovery by Giovanni Cassini on 25 October 1671.

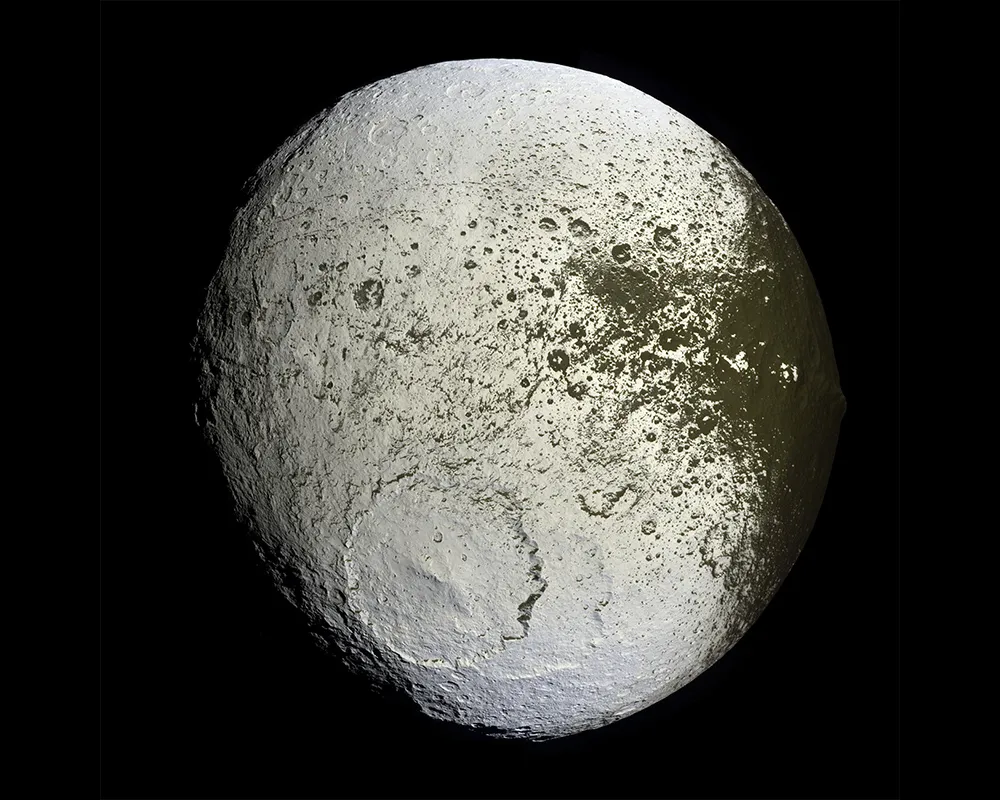

It owes its nickname to the fact that part of its surface is bright and icy, while another part is as dark as a blackboard.

Cassini drew two conclusions, one of which was right and the other wrong.

Cassini found that Iapetus was an easy telescopic object when west of Saturn in its orbit, but when it moved round to the east of Saturn he could not see it at all.

Iapetus's orbital period is 79 days, so Cassini lost it for periods of weeks.

He rightly reasoned that Iapetus must have hemispheres of different albedo and that the rotation period must be synchronous (ie, equal to the orbital period), so that the same hemisphere must face Saturn all the time; when west of Saturn the bright hemisphere was turned towards us.

Using a more powerful telescope, Cassini finally detected Iapetus at eastern elongation in 1705; the magnitude was only just above +13.0.

With my 15-inch reflector I can follow it all round its orbit, but when east of Saturn it is fainter than Cassini’s other three discoveries: Rhea, Tethys and Dione.

Iapetus lies well beyond the other major satellites, at a mean distance of 3.5 million kilometres.

The eccentricity is very low (0.029) but unlike the inner satellites the orbital inclination is 15.5° to Saturn’s equator.

The globe is triaxial (ellipsoid) – its dimensions are 747x749x713km with an equatorial bulge; it was said that the shape was like that of a walnut.

Black on white or white on black?

The first puzzle to be solved (the ‘zebra problem’) was straightforward enough.

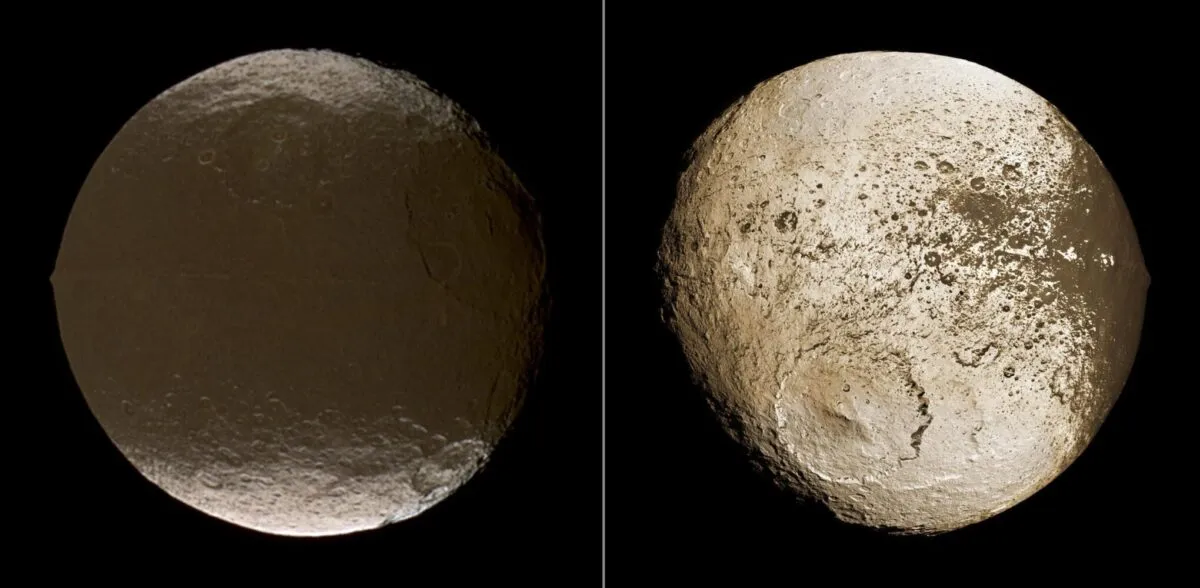

Was Iapetus a bright globe with a dark stain or a dark globe with a white deposit?

Observations of the movement showed that the density was low and it followed that the globe must be made up largely of ice, together with rock, but the nature of the dark deposit remained a mystery.

Carl Sagan even suggested that it was organic – but was it deep or wafer thin?

This was cleared up by the Cassini probe, launched in 1997, orbiting Saturn and sending back amazingly detailed data.

Iapetus's ring

The Voyager spacecraft, successful though they were, had shown little on Iapetus or the still-more-remote Saturnian moon Phoebe, which had been discovered by WH Pickering in 1898.

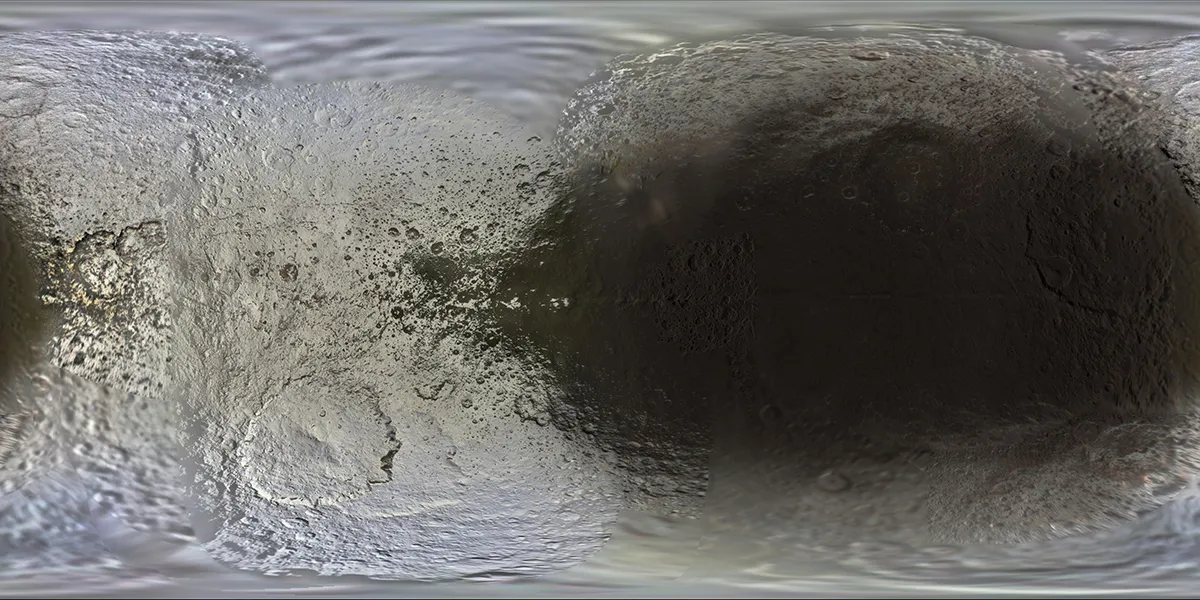

Cassini, though, sent back enough images to provide a map of Iapetus.

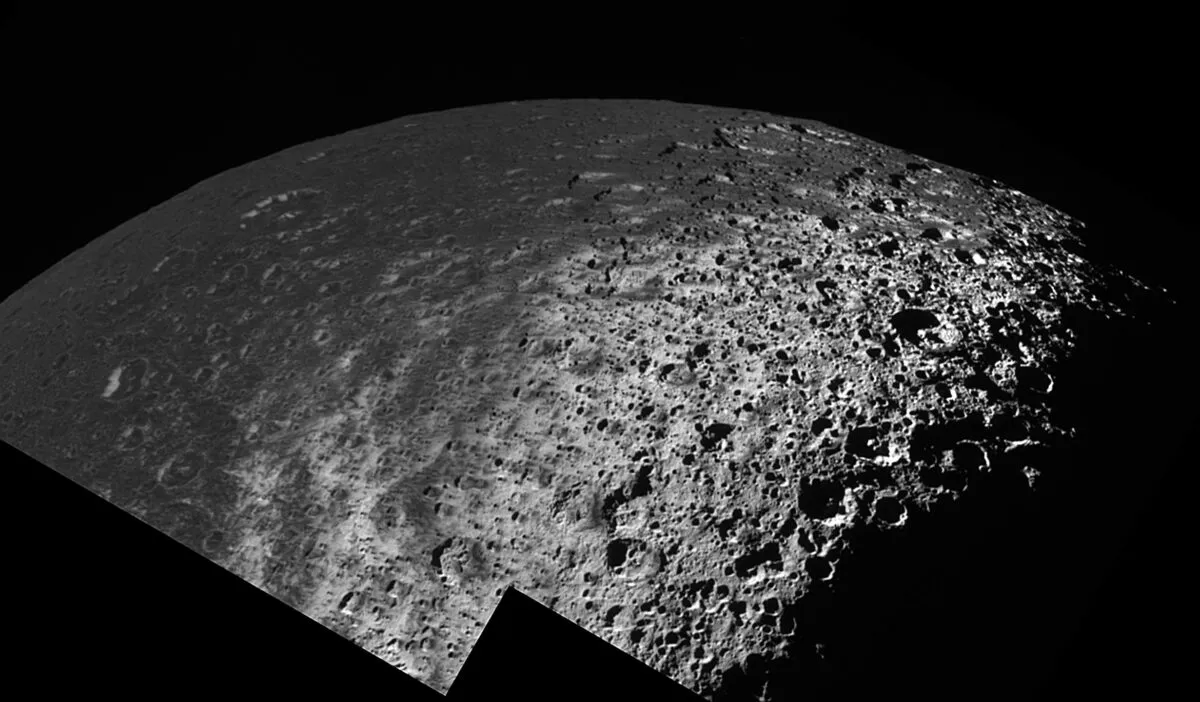

The dark region, on the leading hemisphere, was named Cassini Regio.

The bright region, on the trailing hemisphere, became Roncevaux Terra north of the equator and Saragossa Terra to the south.

Both are mountainous and cratered; one crater, Turgis, is almost 600km in diameter.

The probe also observed a new ring, moving in the orbit of Phoebe; it had been missed earlier because it mainly radiates in the infrared and is excessively difficult to detect at visual wavelengths.

This explained the ‘zebra problem’. Dark dust scattered off the ring migrates inward and falls on Iapetus’s leading hemisphere, staining it.

Remember that Phoebe has retrograde motion and this must also be the case for the particles in its ring.

Iapetus, like all other major satellites, is prograde. This means that the infalling ring particles meet the leading hemisphere of Iapetus virtually head on.

The probe also discovered a huge ridge, 1,300km long, 20km wide and 13km high, running along the centre of Cassini Regio.

There are peaks rising to 20km above the surface below.

Note that it runs along the equator, not along the border between Cassini Regio and Roncevaux Terra, where there are isolated peaks.

The origin of the ridge, which runs halfway around the moon, is unclear.

There have been suggestions that it is material from a collapsed ring, either of Saturn or of Iapetus itself, but this is pure speculation and we have to admit that the ridge remains a mystery.

It is worth noting that Cassini Regio is 15°C warmer than Roncevaux Terra and, at its warmest, may rise to a torrid –143°C. The dark coating can hardly be more than 12cm deep.

Exploring Iapetus

Any idea of sending crewed expeditions to Iapetus is science fiction at the present time.

The radiation problem is only one of the many hazards to be overcome and we really do not have the slightest idea of how to deal with it; our Saturnian astronauts will have to be in space, unprotected, for months.

It is true that Saturn’s own radiation belts are weaker than those of Jupiter and moreover Iapetus moves outside the most dangerous of them, but this is no help on the outward journey.

It is also probable that when (or if) it can ever be attempted, Iapetus will be relegated to third place in order of priority.

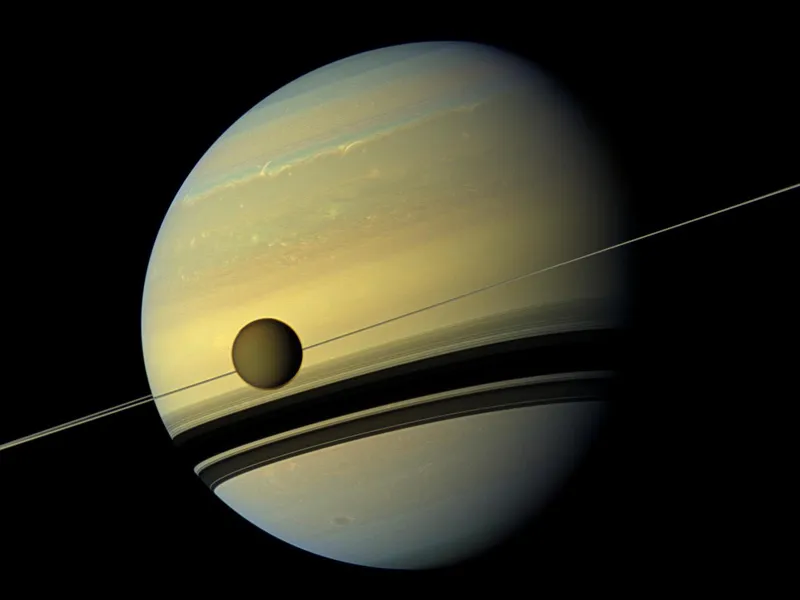

First on the list must surely be Titan – larger than Mercury, with a dense atmosphere and lakes of liquid methane.

Next will come Enceladus, which I regard as the weirdest world in the entire Solar System.

Its diameter is a mere 50km, smaller than that of the largest crater on Iapetus, and yet it is violently active, with geysers of water bursting from fissures in the crust.

There must be a warm underground ocean – no other explanation seems admissible – but how it got there and how it is regularly replenished, we know not.

I fully expect that Titan and Enceladus will be reached first. Then it will be the turn of Iapetus.

The travellers to Iapetus will have one great advantage.

All the other major satellites move in the plane of the rings, so that the observer on them would always see the rings edgewise-on.

Iapetus is different. Its orbit is well inclined to the ring-plane, and our astronauts will be able to admire the rings as they show up as a magnificent arc in the Iapetian sky.

This guide originally appeared in the June 2011 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.