Inferior planets are Solar System planets whose orbits lie between Earth and the Sun; superior planets' orbit lies beyond Earth.

The difference between inferior and superior planets has a major bearing on the planets in our Solar System and how we observe them.

More practical stargazing

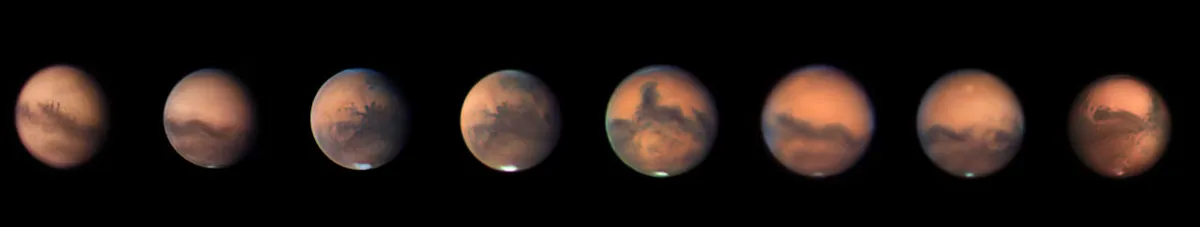

To the naked eye, Mercury and Venus appear as bright star-like entities, but through a telescope they exhibit phases in much the same way as the Moon.

It was Galileo’s discovery that Venus parades through a series of phases in 1610 that provided unassailable proof that Copernicus had been right all along: the Sun really was the centre of the Solar System.

But why do we see phases on these worlds and not, say, Saturn? This is where the definitions of inferior and superior planets become important.

Inferior planets

Mercury and Venus are both known as inferior planets. They are the only two inferior planets in the Solar System.

The term 'inferior' in relation to a planet doesn't mean they're of a lesser class.

An inferior planet is one whose orbit lies entirely within Earth’s orbit.

It’s because of this position relative to Earth that we can see Venus and Mercury's changing illumination, though the phase cycle doesn’t quite play out in the same way as it does with the Moon.

The basic tenets are the same, but the outcome in terms of what we can see is a little different.

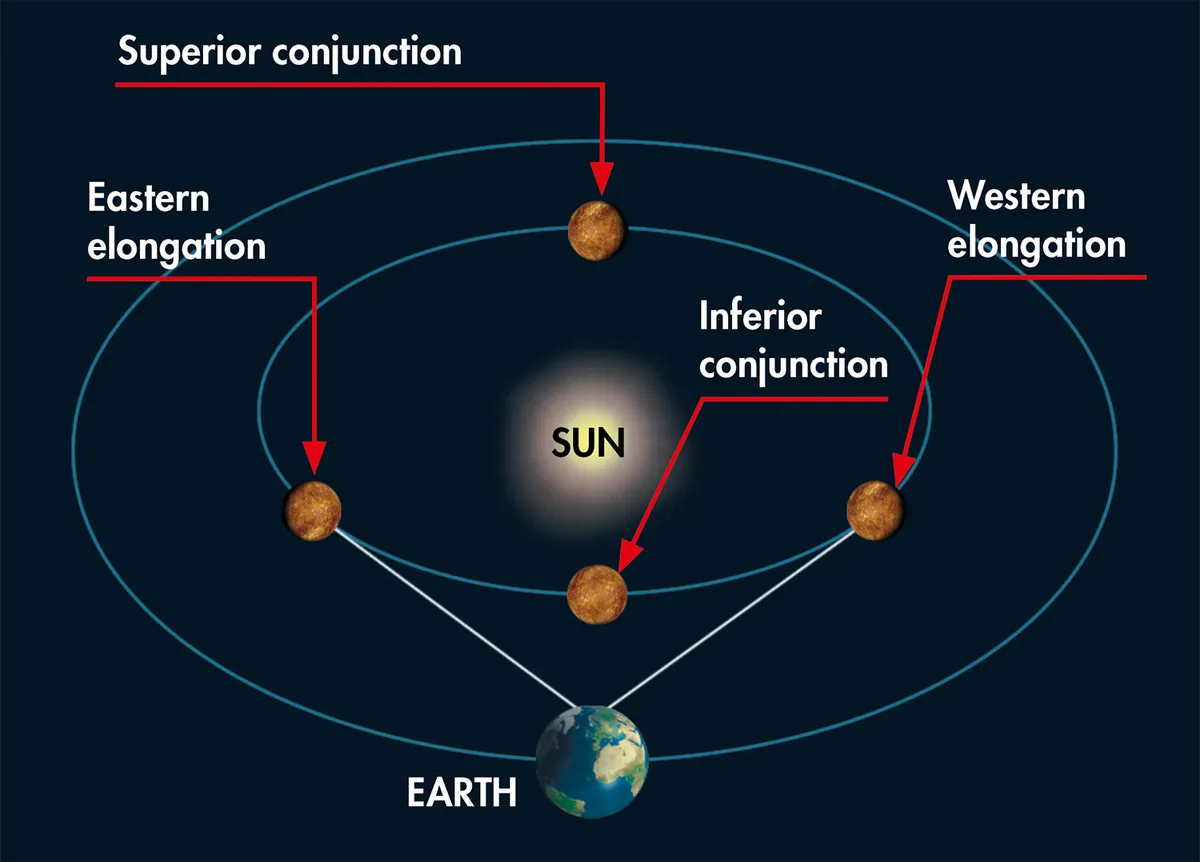

Imagine you’re looking down on Earth, the Sun and Mercury (though this example applies to Venus), and they're in a line with Mercury in the middle.

This is the point you might colloquially call ‘new Mercury’, but is properly referred to as inferior conjunction.

Here the planet is invisible to us on Earth. Even if you could pick it out of the solar glare, there is no light shining on the Mercurian hemisphere facing Earth.

As the planet moves through its orbit, it gains angular distance from the Sun, causing it to appear in the morning sky as a crescent.

Mercury gains its half-illuminated phase (known as dichotomy) when it reaches its greatest angular separation from our star, a point known as its greatest elongation.

Venus does not. It reaches dichotomy a few days after its greatest elongation when in the morning sky and a few days early when in the evening sky.

From here Mercury becomes gibbous and begins to edge closer the Sun, eventually becoming lost in the solar glare once more as it approaches its ‘full’ phase, or superior conjunction, on the far side of our star.

When the phases begin to play out in reverse, the planet will emerge into the evening sky.

Superior planets

This is all starkly different to the situation of Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, the superior planets, so-called because their orbits all lie beyond Earth’s.

We can never see these planets in a new or crescent phase.

Of the five superior planets, only Mars can resemble a gibbous phase, and even then it is a long way from the classic, 75% illuminated bulge.

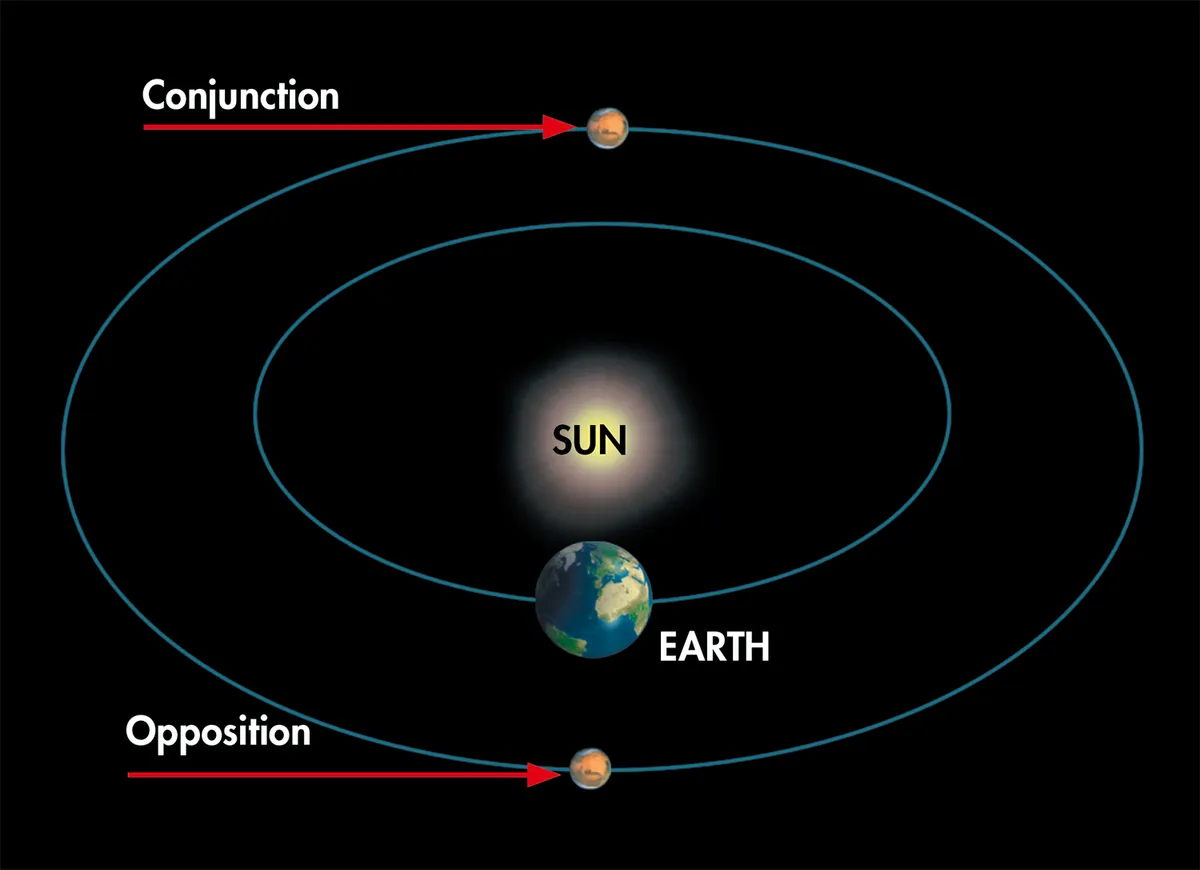

There are two points of note in the orbit of a superior planet.

The first is opposition, when the Sun, Earth and planet align with the Earth in the middle.

For observers on Earth, the superior planet at opposition appears to be in the opposite part of the sky to the Sun.

The second is conjunction, when the Sun is in the middle of the alignment. In this case the planet is lost in solar glare.

Observing superior planets

Astronomers tend to look forward to oppositions, because this is when a superior planet looks its best.

Planets at opposition are often at the closest point in their orbits to Earth, so can appear bigger and brighter.

Typically they are also visible all night long and culminate (reach their highest point in the sky) in darkness.

For Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, oppositions can offer a huge boost to a planet’s observing prospects.

Uranus and Neptune, being dimmer and more distant, less so.

Observing inferior planets

For the inferior planets, the situation is a little more complex because they never stray too far from the Sun.

They are typically stuck low down in the sky and rise shortly before the Sun or set not long after it.

The best time to see an inferior planet is arguably when it's at greatest elongation, as this is when the period between Sun and planet rising or setting is at its greatest.

For Venus the greatest elongation is 45-47°, while for Mercury it is 18-28°. The variation stems from both planets having elliptical orbits.

You should also bear in mind that the apparent diameter of any planet will change as it moves through its orbit.

For the inferior planets, this means that fuller it becomes, the smaller the apparent size of its disc.

Consequently, and somewhat counterintuitively, Venus is at its brightest when it is a slender crescent because it is much closer to Earth at this time.

If you think this sounds a little bit confusing, you have not been the only one.

The Ancient Greeks were convinced that the Venus that appeared in the morning and the evening were different celestial objects.

To them, the body known as the Morning Star was Phosphorus and the Evening Star was Hesperus. They fell into the same trap with Mercury too: it bore the names Apollo and Hermes, respectively.

This guide originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.