Over ten years ago, The Sky at Night co-presenter Chris Lintott started Galaxy Zoo, a citizen science project to classify galaxies. It was an instant success. Before long, with the help of others, he initiated similar ‘distributed science’ projects like Solar Stormwatch (on solar flares) and Moon Zoo (on lunar crater counts).

At present, the Zooniverse encompasses over 70 projects in various areas of science, including Penguin Watch.

Prof Lintott's new book The Crowd & The Cosmos describes the origin and evolution of the Zooniverse, with a strong focus on the astronomy projects.

We got the chance to chat to Lintott about the advantages of citizen science, and whether robot astronomers might ever replace humans.

How have advances in technology influenced the field of citizen science?

Citizen science is an old idea for astronomers - observers with back garden equipment have been monitoring the planets, finding supernovae and counting meteors for centuries!

The advance in technology has created new opportunities - professional surveys of the sky produce a wealth of data, and the advent of the web means we can all get our hands on it.

That means that everyone can explore the Universe together and make some fascinating discoveries along the way.

What have been the biggest discoveries of Galaxy Zoo?

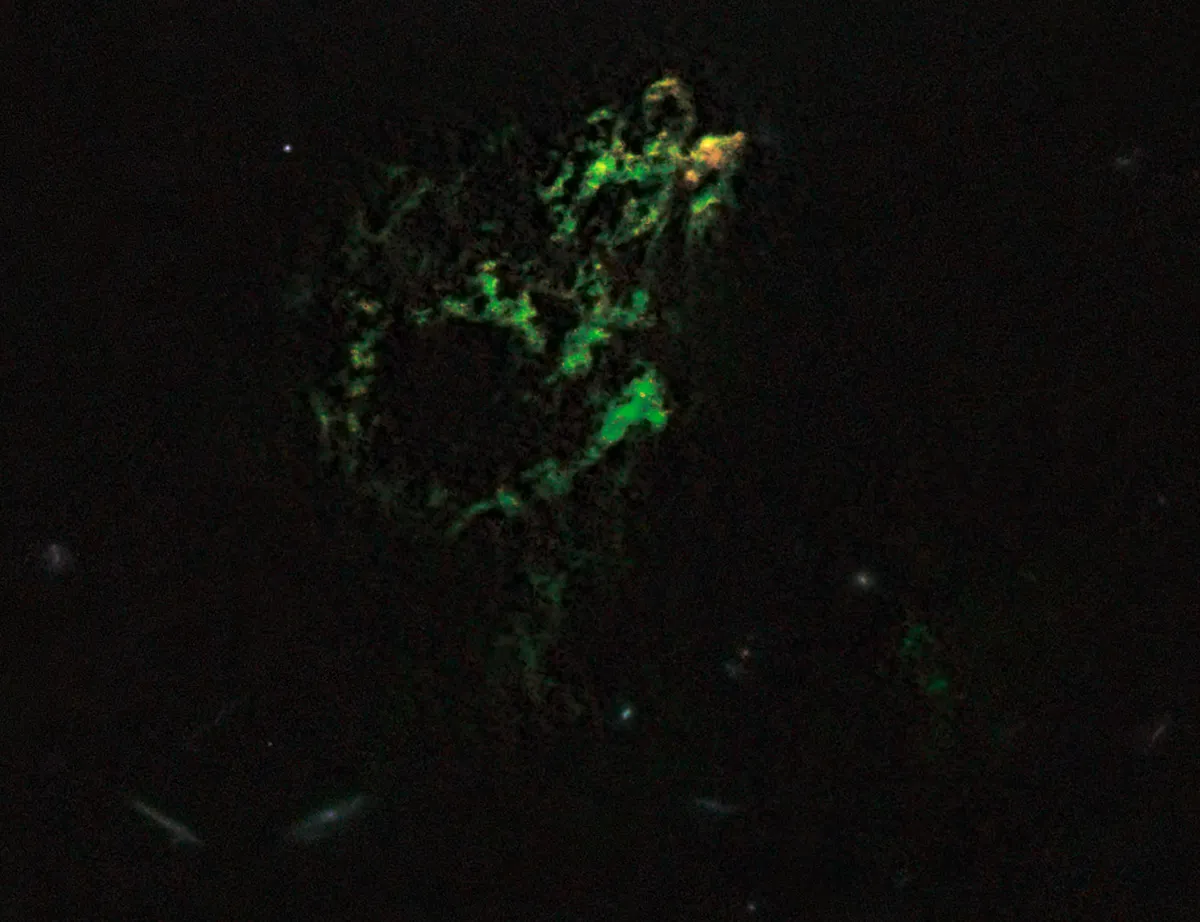

Volunteers keep on finding the unusual and unexpected. Probably my favourite is Hanny's Voorwerp, a galaxy-sized glowing gas cloud which was discovered by Dutch schoolteacher Hanny van Arkel.

The gas in the Voorwerp is excited by the neighbouring galaxy, which would once have been our nearest quasar.

A discovery that started with Hanny asking a simple question - 'What is this thing?' - ended up involving observatories around the world and in space to find an answer.

How important is citizen science to advancing scientific discovery? How much further behind would we be without projects like this?

The results from Galaxy Zoo and our other citizen science projects have really become part of the standard toolkit astronomers use to explore the Universe; hundreds and hundreds of papers make use of the results.

I'm really excited that projects like the upcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope - an enormous telescope that will make the grandest survey of the sky to date - are planning from the beginning to use citizen science to deal with the volume of data that's coming our way.

Are humans more useful than big smart computers?

Since we started Galaxy Zoo people have been assuming computers would take over, and it's certainly true that automated pattern recognition has come a long way in the last decade.

What we're finding is that combining human and machine classification gives better results than either on their own - the machines do the bulk of the work, but you still get that human ability to be surprised and to deal with the unexpected.

We need to work with our robot colleagues, not see them as competition!