The James Webb Space Telescope is set to open up new windows to help astronomers explore exoplanets and their atmospheres.

JWST will be positioned at L2 (Lagrange point 2) on the far side of Earth to the Sun, where the gravity of the two bodies and the centrifugal force balance each other.

After a 6-month testing process it will begin scientific observations.

The global astronomical community will get its first chance to use this new platform through the Cycle 1 General Observers (GO) program.

This project gives astronomers a chance to use some of the 6,000 hours on offer for their research.

Here are three of their proposals, utilising the James Webb Space Telescope to discover more about the incredible worlds orbiting stars beyond our Solar System.

Observing mini Jupiters

Charles A Beichman at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and his team will use JWST’s coronagraph to attempt to image any small gas giant planets (down to half of Jupiter’s radius) around our closest Sun-like star, Alpha Centauri A, in their proposal Searching Our Closest Stellar Neighbor for Planets and Zodiacal Emission.

They’ll focus their search within three Astronomical Units of the star, where calculations predict a region of orbital stability, safe from the gravitational disruption of its binary twin Alpha Centauri B.

They will also try to see out to the interplanetary dust, which in our Solar System produces the zodiacal light.

The team admits this is a high-risk attempt, but the chance of imaging a planet around our closest stellar neighbour is thrilling.

Searching for habitable planets

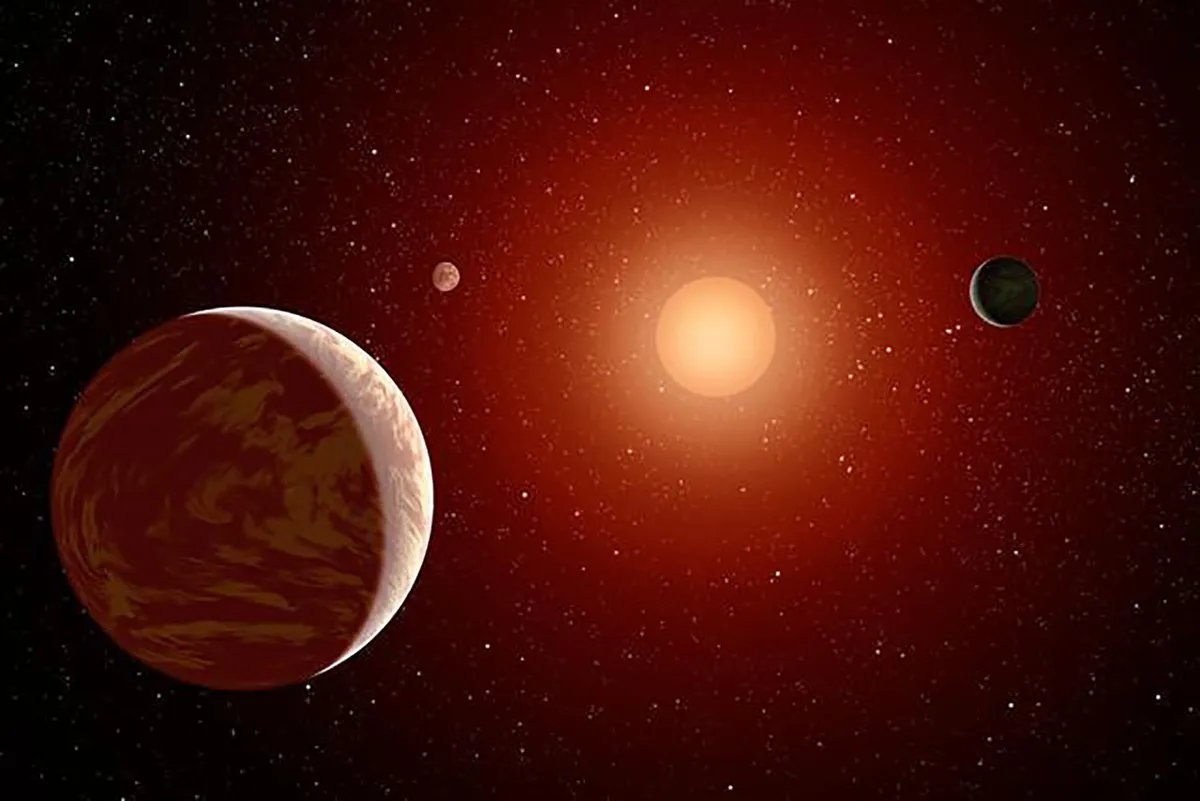

Meanwhile, in the proposal Tell Me How I’m Supposed To Breathe With No Air: Measuring the Prevalence and Diversity of M-Dwarf Planet Atmospheres, Kevin Stevenson at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and his team will observe nine small, terrestrial planets orbiting the nearest M-class red dwarf stars.

They will be looking for the infrared spectral signatures of carbon dioxide and methane gases, and therefore whether this category of worlds are able to cling on to an atmosphere.

It’s a key question about the potential of habitability for life. M-class dwarfs are the most numerous kind of star in the Galaxy and their planets offer the only chance we’ll have in the next decade to measure their spectrum.

This proposal illustrates the strength of a good name – taken from song lyrics by Jordin Sparks, the 2007 American Idol winner!

Analysing low-mass sugar puffs

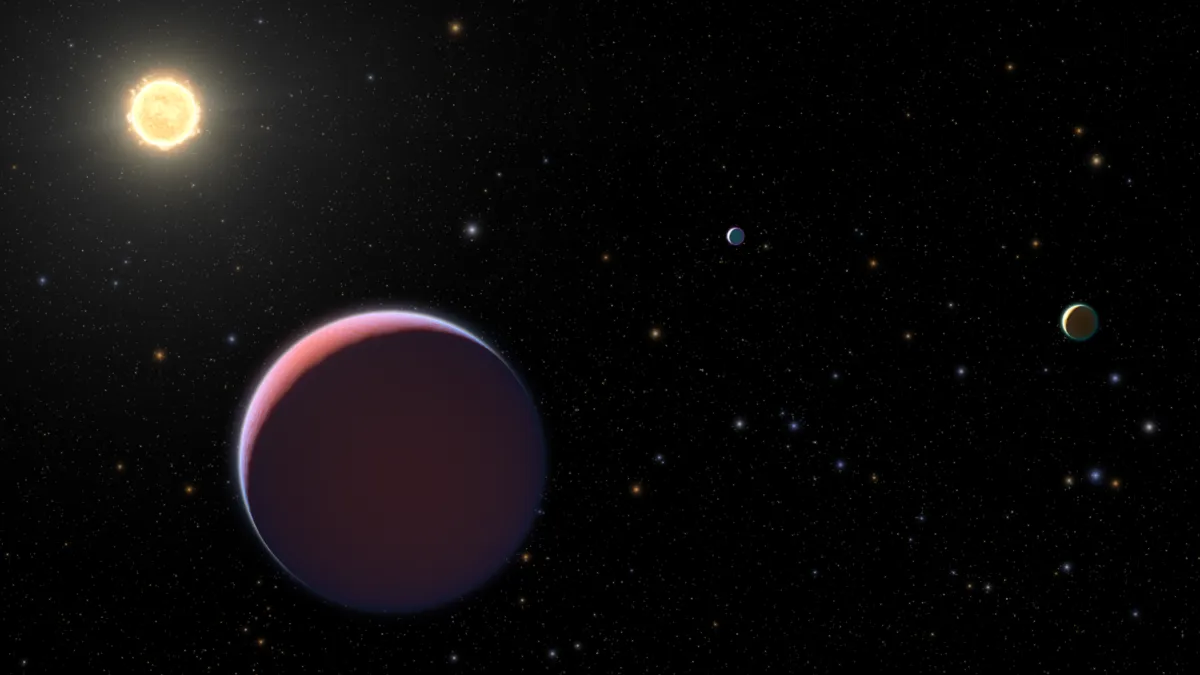

In the proposal Unveiling the Nature of the Impossible Planets, Peter Gao at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and his team (including members from the University of Oxford) plan to study a mysterious kind of exoplanet known as a ‘super-puff’.

This type of planet is relatively low-mass (less than Neptune), but seems to have a huge radius, its atmosphere apparently expanded out by the heat of its star.

Such a planet ought to have suffered catastrophic atmospheric loss, which makes its existence a mystery.

One proposed solution is that it only appears to be much larger than it actually is because it is enshrouded in a high-altitude haze layer.

Gao has been awarded 12 hours of observing time to check this hypothesis, using JWST’s near-infrared spectrometer to look for a chemical composition that would indicate a haze in the ‘super-puff’ planet Kepler-51b.

This is one of three super-puff planets orbiting the same star – all Jupiter-sized, but with masses only a few times that of Earth.

This article originally appeared in the February 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.