Johannes Hevelius, the first important Moon mapper, was born on 28 January 1611 in the town of Danzig, now known as Gdansk, where he played an important role in local municipal affairs as well as in astronomy.

Although he was of German and Czech ethnicity, and his first language was German, he was quite definitely Polish.

Danzig was under Polish control and it would really be more correct to call him Jan Heweliusz, though we always use the Latinised form.

Discover our pick of the greatest and most famous astronomers of all time

Early life

Johannes Hevelius's father Abraham owned a profitable brewery and there were long periods in Hevelius’s life when he had to put astronomy aside and run the family business.

He had three brothers and six sisters but was the only boy to survive early childhood.

He studied at the Gymnasium in Danzig for six years and was then sent to school in the Polish- speaking village of Gondeltsch.

Here the mathematics teacher, Peter Krüger, introduced him to astronomy.

The boy showed keen interest and aptitude, and henceforth astronomy was his main interest.

Running the brewery was essential but was frankly regarded as a nuisance.

He married Katharina Rebeschke, daughter of a wealthy citizen of Danzig. The marriage was happy and Katharina helped with the administrative work of the brewery.

She died in 1662 and Hevelius then married Elisabetha Koopman.

She was only 16 but became an enthusiastic follower of astronomy – it has even been said that she was the first female astronomer of the Christian era.

Johannes Hevelius astronomy career

By now Hevelius was in touch with many of the leading astronomers of the day, including Edmond Halley, Robert Hooke and John Flamsteed in England.

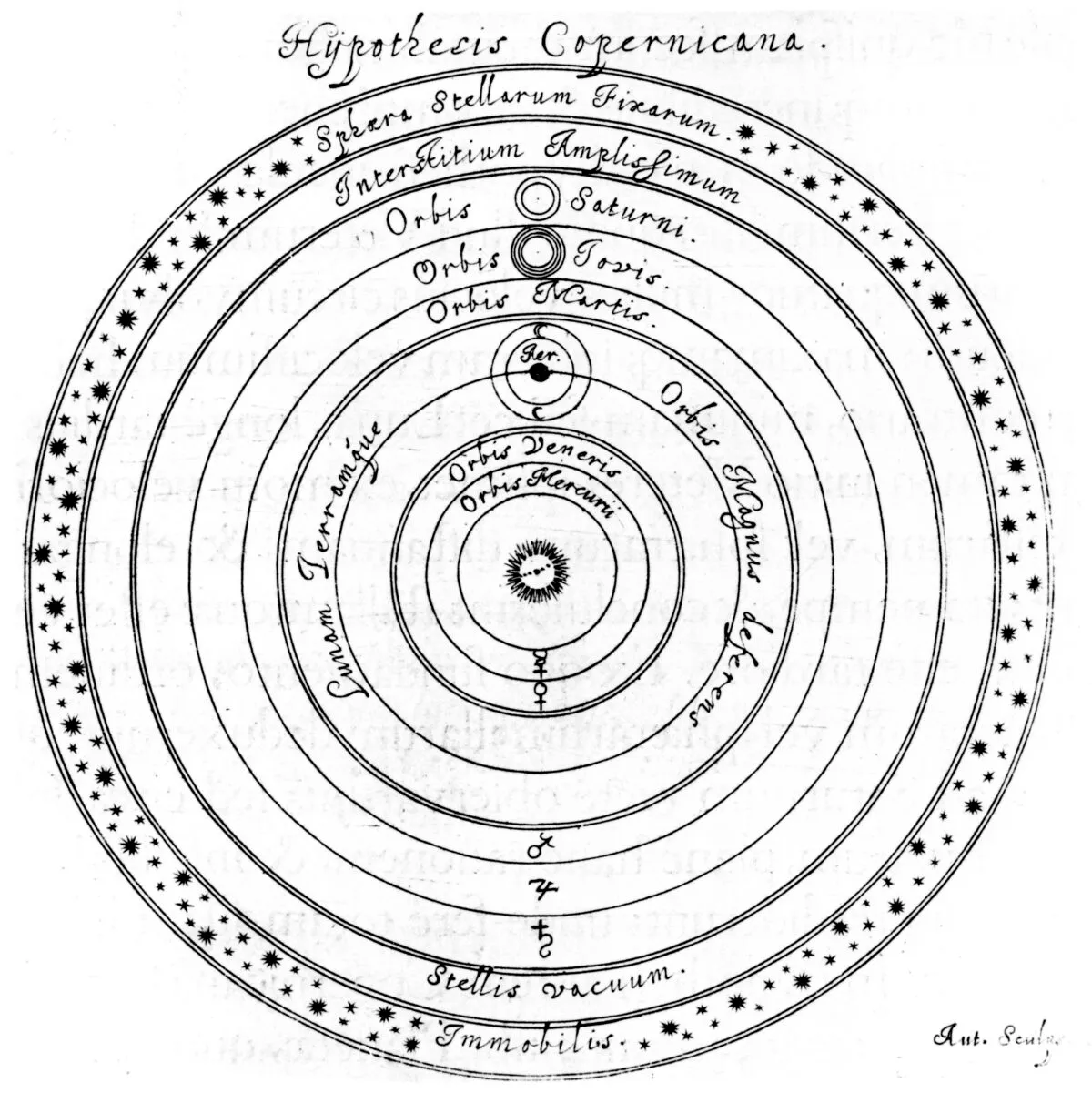

He also made his own telescopes. In 1641 he built an observatory on the roofs of his three connected houses in Danzig, equipping it with the three best instruments he could make or buy.

This was the time of the small-aperture, immensely long refractors (reflectors did not come upon the scene until after 1670, when Newton made the first).

Hevelius built a telescope of 45m focal length with a tube made of wood and wire.

The rooftop observatory welcomed many visitors, including the King and Queen of Poland.

Hevelius was admitted to England’s Royal Society in 1664 – the first Polish member.

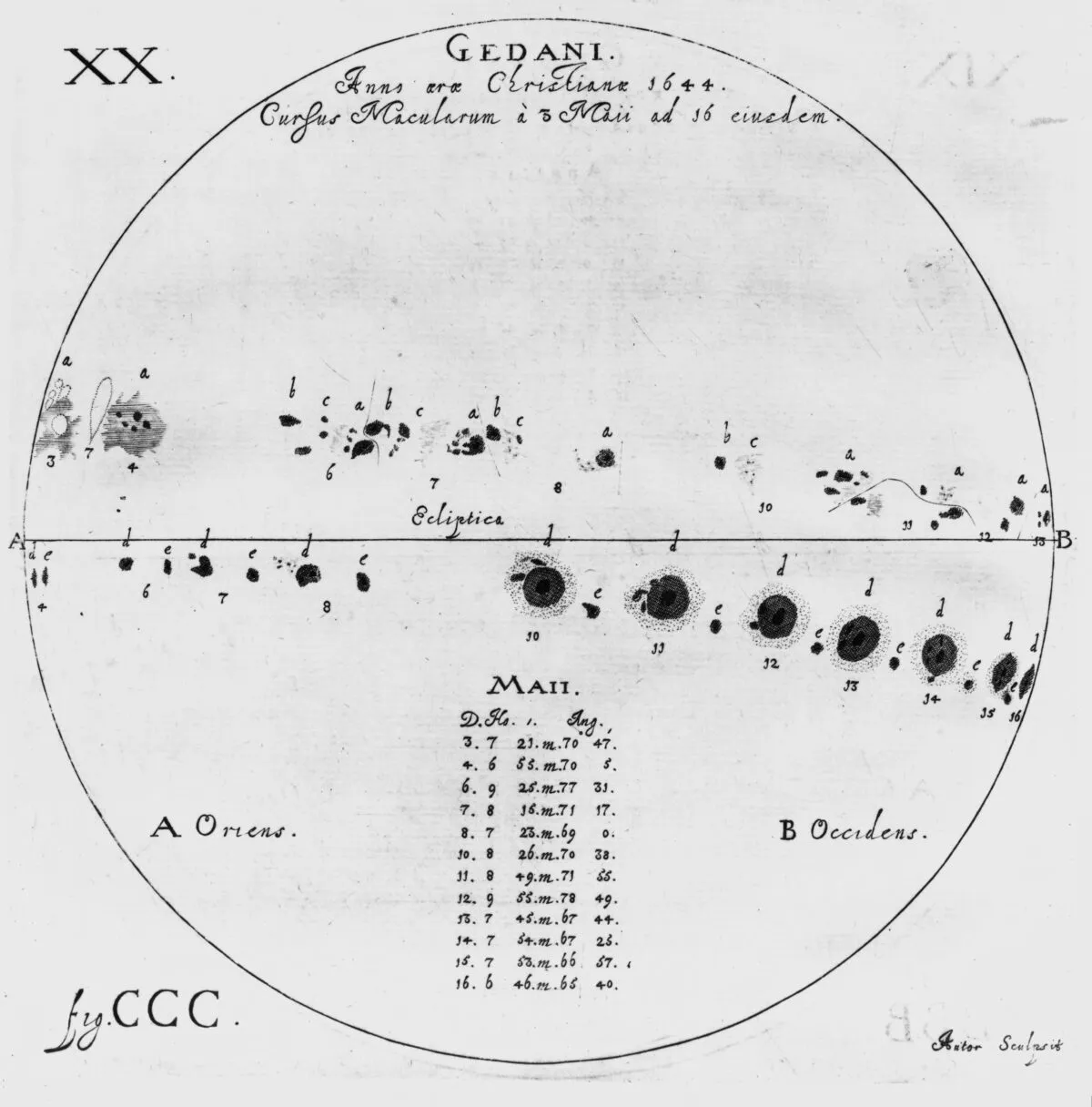

Hevelius became a serious observer, in particular studying sunspots; he also discovered four comets.

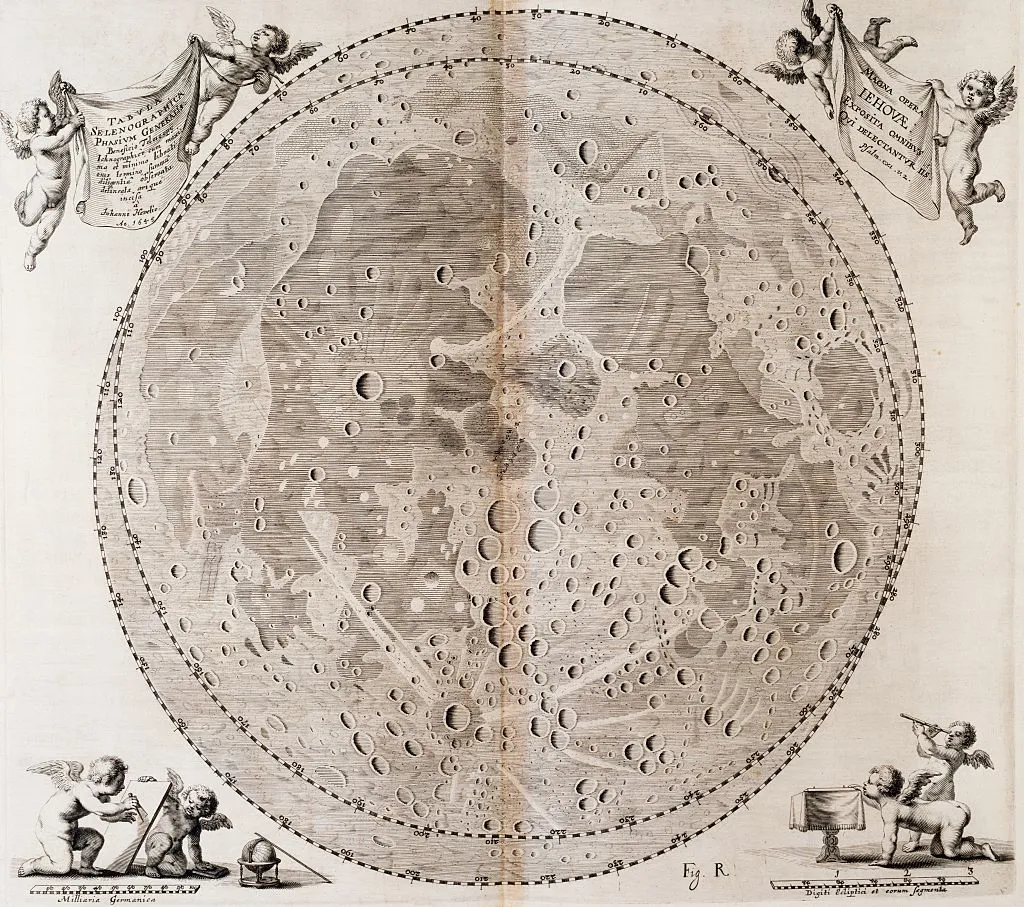

However, he is best remembered for his map of the Moon, completed in 1647, together with a text describing the surface features and the discovery of the libration in longitude.

There had been earlier lunar mappers such as Thomas Harriot and Galileo, but Hevelius’s map was more accurate and he deserves to be regarded as the founder of lunar topography.

He gave names to some of the features but his nomenclature was superseded in 1651 by Giovanni Battista Riccioli’s.

The crater we now call Plato was known to Hevelius as ‘the great Black Lake’!

Fire damage

Disaster struck in 1679 when a fire destroyed his observatory, together with his instruments and most of his books and papers.

Most people would have given up but Hevelius, to his everlasting credit, did not.

Helped by his wife, he set to work rebuilding the observatory and even made another 45m-focal-length telescope.

It was impossible to construct a tube as long as that, so Hevelius dispensed with any continuous tube and used a series of rings, with the object-glass at one end and the eyepiece at the other.

The ‘tubeless telescope’ must have been incredibly difficult to use and the slightest breeze would have made it quiver.

Nevertheless, Hevelius persisted with it, which makes his star catalogue an even more remarkable achievement.

Johannes Hevelius star maps and constellations

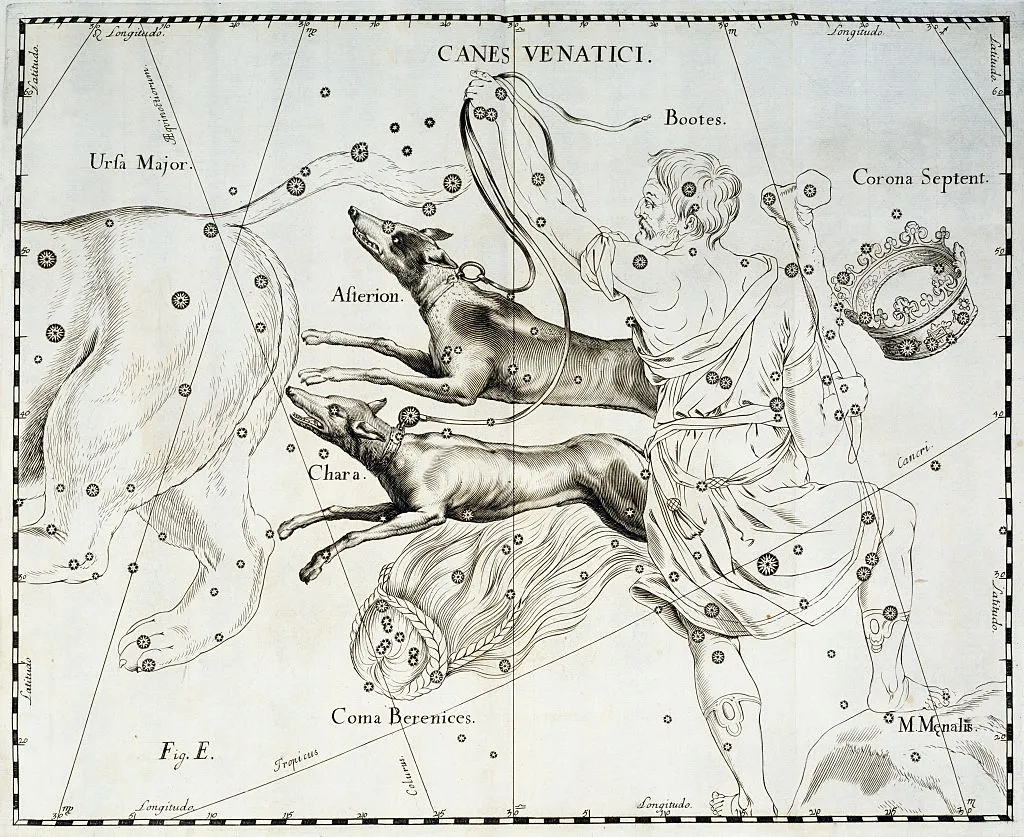

Johannes Hevelius’s star maps included nine new constellations, all of which have – rather surprisingly – survived later cuts.

Among these are Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs (containing the bright magnetic variable star Cor Caroli).

Vulpecula, the Fox (originally Vulpecula et Anser, the Fox and Goose, containing the Dumbbell Nebula).

Monoceros, the Unicorn, which is a rich region of the Milky Way

Sextans, the Sextant (originally Sextans Uraniae, containing the Spindle Galaxy).

There was also Scutum, the Shield, within which is the lovely Wild Duck Cluster. The Shield itself is very rich.

On the other hand there seems little excuse for Leo Minor, the Little Lion; Lacerta, the Lizard; or Camelopardalis and Lynx, the Giraffe and the Lynx respectively.

They are large but decidedly barren, though Lynx does contain one third-magnitude star, the reddish M-type Alpha Lyncis, as well as NGC 2419, a globular cluster that seems to be escaping from the Milky Way.

Astronomers of this era could seldom resist meddling with the accepted constellation patterns, so that the maps became more and more cluttered and confused.

Find out more about this in our guide to forgotten constellations.

Even Tycho Brahe and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, as well as Hevelius, were not immune, though the far-southern constellations did have to be divided up.

Naked-eye observing

Strangely, Hevelius used his measuring instruments with the naked eye.

This led to a long and acrimonious dispute with Hooke, who stressed the importance of using telescopic sights.

Of course, Hooke was right and Hevelius wrong but the arguments raged.

Even the popular Halley was unable to calm the participants down and the situation was not helped by the fact that Hooke was almost universally disliked.

Hevelius never did become reconciled to using telescopic sights.

Death and legacy

Johannes Hevelius died in Danzig on 28 January 1687, and his widow Elisabetha made sure that his surviving observations plus three books were published.

Later, a large lunar crater was named in his honour.

Unfortunately, the copper-plate of his map of the Moon was lost. According to one story, it was melted down and made into a teapot.

It is tragic that so much of his work was lost in the fire, but enough remains to prove that Johannes Hevelius was one of the greatest of the early astronomers.

Who are your favourite early astronomers? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com.

This article was published in the January 2011 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine