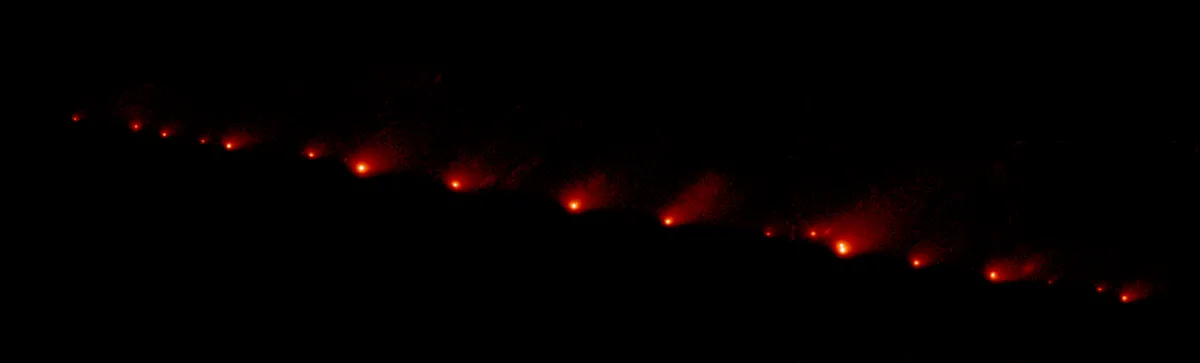

The spectacular collision of the comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 into Jupiter in 1994 was watched closely by observatories and space probes, and made headlines around the world.

Since 2010, six impact flashes on Jupiter have been serendipitously observed, including by amateur astronomers.

A simple brightness measurement allows for an estimate of the energy of such impacts, but far more accurate calculations can be made if they are recorded at several different wavelengths.

Ko Arimatsu, at the Astronomical Observatory, Kyoto University, and his colleagues have been using the Planetary ObservatioN Camera for Optical Transient Surveys (PONCOTS), dedicated to monitoring flashes on Jupiter.

The system is made up of a 28cm Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope on a rooftop at the university, equipped with two CMOS cameras.

This setup allows the astronomers to observe flashes on Jupiter at three different wavelengths simultaneously: the V visible band in the yellow and two near-infrared bands.

On 15 October 2021, Arimatsu and his team observed a particularly bright impact flash on Jupiter, occurring within the north tropical zone.

The peak apparent brightness of the flash in the visible band was mag. 4.7, equivalent to an absolute magnitude of –29.0: roughly 300 times brighter than the Sun at Jupiter.

And because their PONCOTS system can observe with a high frame rate across three wavelengths simultaneously, they were able to record this impact flash with unprecedented detail.

How big was the bang?

From the three light curves, they calculated that the temperature of the resultant fireball in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter was over 8,000°C.

The impactor would have struck with a kinetic energy of around 7 million billion joules – an explosion equivalent to two megatons of TNT.

This is comparable to that of the Tunguska event, when a meteoroid exploded over eastern Siberia in 1908 and flattened over 2,000 square kilometres of forest: the largest impact event on Earth in recorded history.

From the energy of the Jovian impact, the impactor was estimated to have a mass of around four million kg and a diameter of 16–31 metres.

This is the most energetic impact flash observed in the Solar System since Shoemaker–Levy 9.

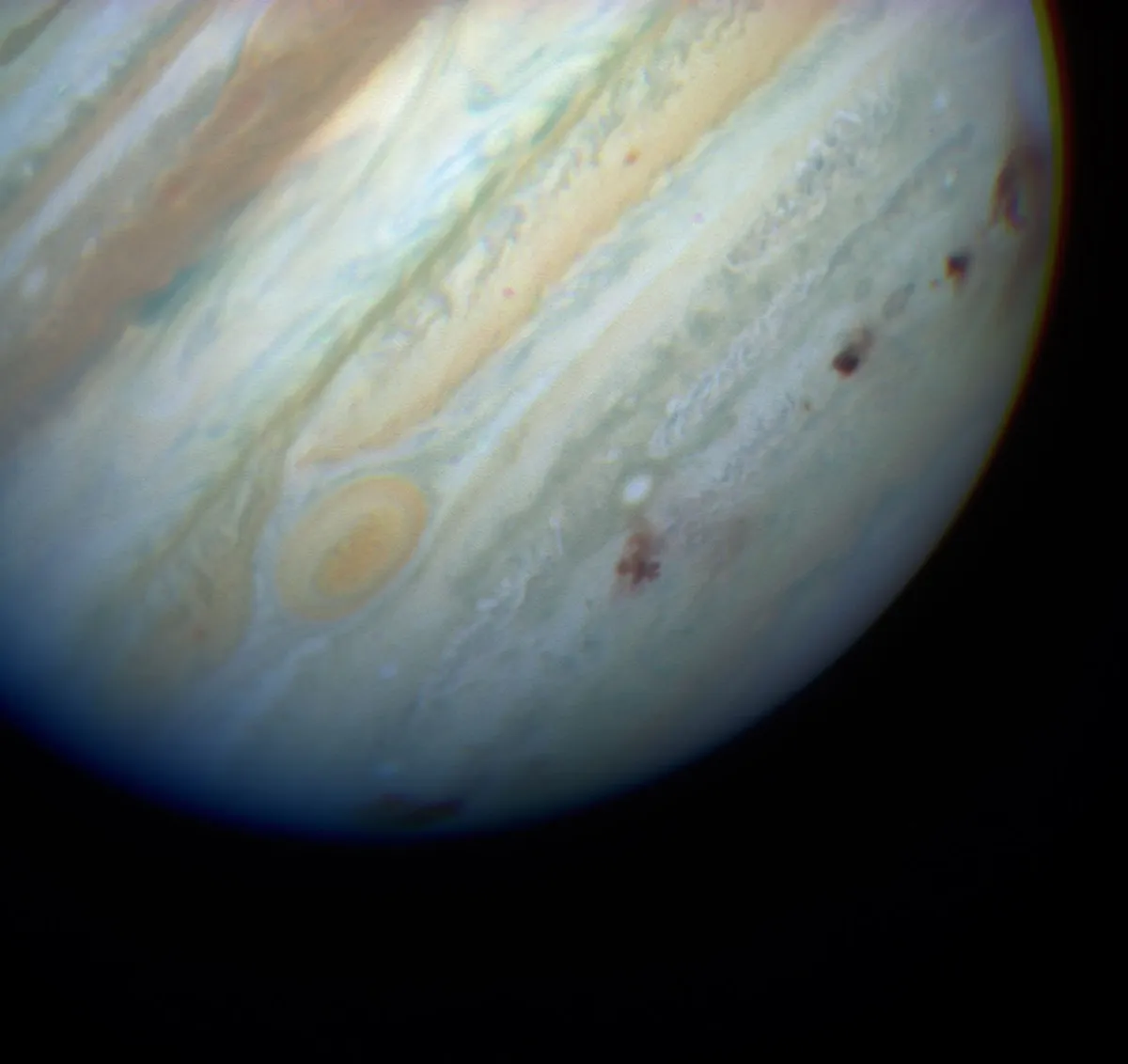

Those created a string of giant dark patches in the Jovian atmosphere visible from Earth, scars that persisted for months.

Arimatsu and his team were hopeful that their detected impact might also have left observable marks, but their follow-up observation 16 minutes after the event could find no signs.

The Juno spacecraft, in orbit around the planet, was able to observe the impact site 28 hours later, but even with such a front-row view it too failed to spot any clear debris features.

Arimatsu speculates that this could be due to the fact that their impactor was smaller than those of Shoemaker–Levy 9 and so any impact features were much more limited and shortlived.

Based on their observations, Arimatsu estimates that such Tunguska-like impact events on Jupiter occur roughly once a year – hundreds to thousands of times more often than on Earth – and so they’re waiting eagerly to catch the next one!

Lewis Dartnellwas reading Detection of an Extremely Large Impact Flash on Jupiter by High-cadence Multiwavelength Observations by Ko Arimatsu et al.

Read it online at arxiv.org/abs/2206.01050.

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.