The Lagrangian points around an orbiting body are special points in space, where the gravitation of the Sun pulling in and the centrifugal force of our motion flinging out act to balance each other out.

These regions around the Earth are very useful for spacecraft.

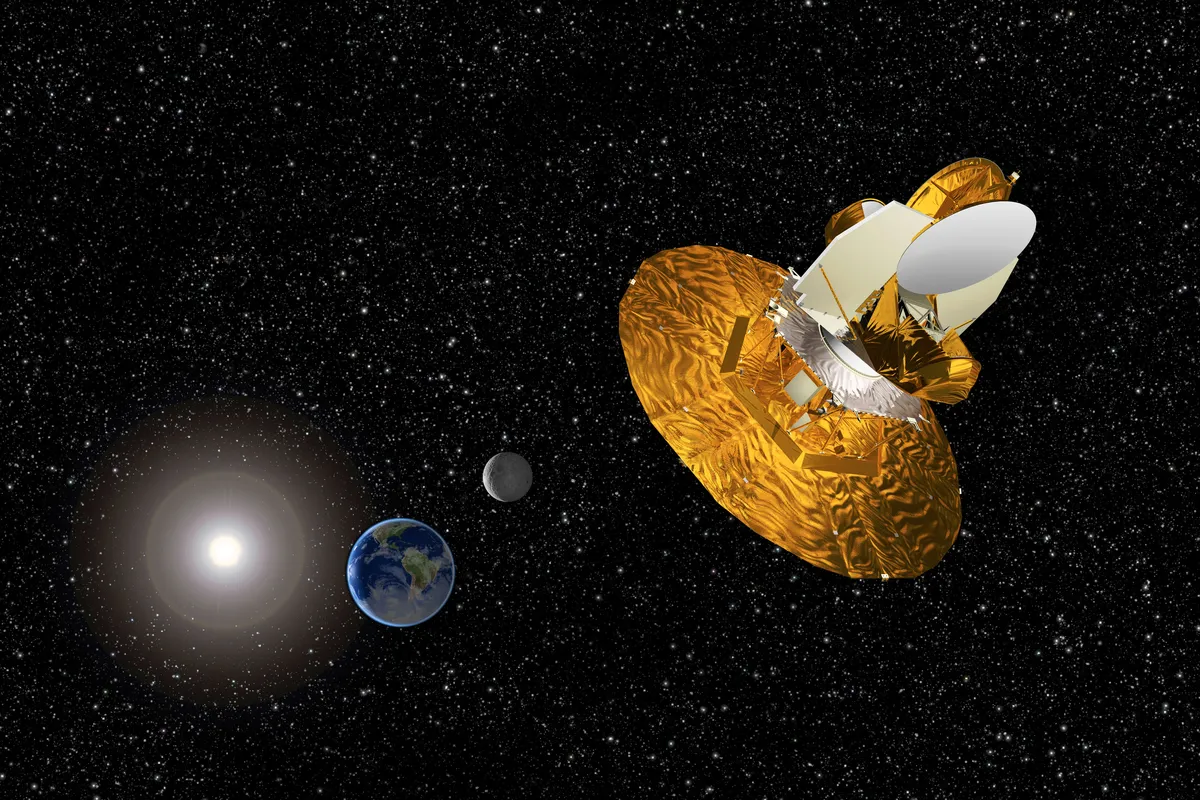

For example, the SOHO solar observatory has been parked in the L1 Lagrangian point between the Sun and Earth, and the WMAP probe that mapped the remnant heat from the Big Bang is at L2 beyond the Earth.

There are also Lagrangian regions situated 60° leading and trailing any massive object in its orbit.

In Jupiter’s case, its L4 and L5 regions are each populated by a swarm of asteroids.

They are known collectively as the Trojans, with the largest of them named Agamemnon, Achilles and Hector.

The origin of the Trojan asteroids

These Trojan asteroids aren’t thought to have formed at 5.2 AU, the distance of Jupiter’s current orbit from the Sun, but it’s unclear exactly where they came from.

Were they originally icy planetesimals from beyond Neptune, scattered and then captured by Jupiter during a period of orbital instability early in Solar System history?

Or perhaps Jupiter collected them when it formed further out, before migrating inward towards the Sun.

Clues to the origin of the Trojans can be provided by studying the distribution of their sizes and surface characteristics.

Kotomi Uehata, at the Department of Planetology, Kobe University, Japan, and her colleagues surveyed the Trojan asteroids in the L5 Lagrangian region, trailing behind Jupiter in its orbit.

They used the Hyper Suprime-Cam (HSC) fitted to the 8.2 m Subaru Telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatory on Hawaii.

They found a total of 189 L5 Trojans down to an apparent magnitude of +24.0, corresponding to objects with a diameter of between 2 km and 10 km.

As expected, the size distribution of these objects follows a power law – there are exponentially more smaller bodies than larger ones.

They also showed, by comparing with an earlier study the team had conducted on the L4 Trojan swarm, that this size distribution is the same for both Trojan swarms, indicating that they came from the same primordial population.

In total, Uehata calculates that there are about 260,000 Trojan asteroids bigger than 1 km trapped in Jupiter’s L4 and L5 Lagrangian regions – roughly 10 times fewer than there are in the main asteroid belt.

Interestingly, though, Uehata discovered that in the L4 swarm ahead of Jupiter, there are about 40% more asteroids with a size larger than 2 km, than there are in the L5 Lagrangian region trailing behind the planet.

This asymmetry in the L4 and L5 populations supports the theory that the Trojans were captured by Jupiter as it formed further out in the Solar System before migrating inward.

The Trojans are a fascinating category of objects, and studying them close-up promises to teach us a great deal about the origin of small icy bodies from further out in the Solar System.

Luckily, there is already a space probe en route to explore asteroids in both of Jupiter’s Trojan swarms.

NASA's Lucy mission, launched in October 2021, will fly by four L4 Trojans (as well as a main-belt asteroid on its way out) before arriving in the L5 swarm in 2033.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Size Distribution of Small Jupiter Trojans in the L5 Swarm by Kotomi Uehata et al. Read it online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.08617.

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.