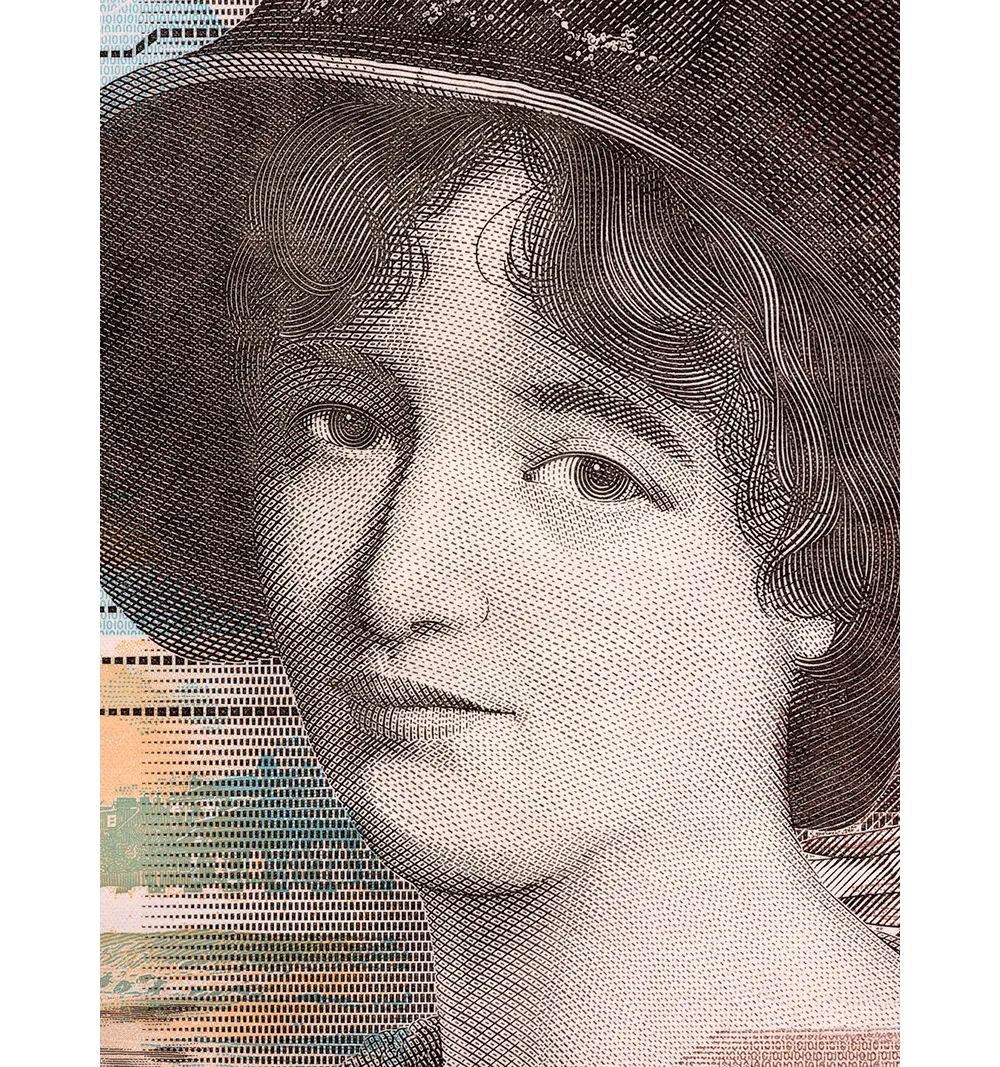

Mary Somerville was a celebrated lady of science of her day. Her name lives on in the Oxford College named after her, there’s a crater on the Moon that bears her name and in 2017 her face featured on the Scottish £10 note. But who was Mary Somerville, and why is she so celebrated?

Like many women within the history of science, her story is complicated. While their male peers were allowed to join and be educated within prestigious institutions, publish original work under their own name and be declared discoverer, inventor and theorist, women did not have those options.

Instead, women often had to rely on generous friends and relatives to educate them and speak up for their achievements.

They had to hide their originality too, disguising it behind respectable female accomplishments such as translation or teaching, which is how it was for Mary Somerville (née Fairfax).

Mary Somerville's historical background

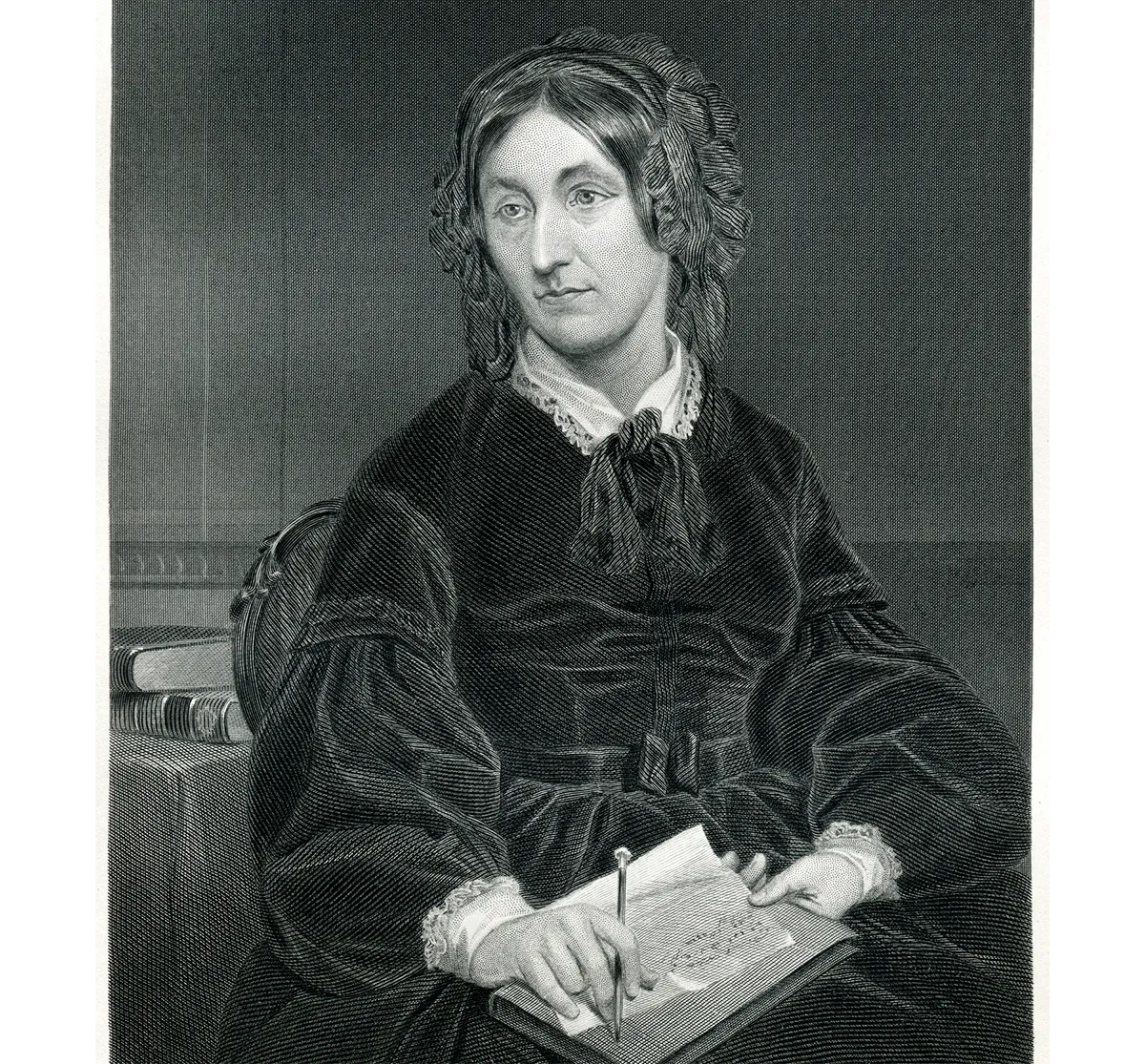

Mary Somerville was born in Scotland at the home of her uncle Dr Thomas Somerville on Boxing Day 1780. Her family were upper middle class (her father was a Vice-Admiral) and comfortable if not wealthy.

At 10 years old Mary was sent away to the first of many schools: a boarding school that taught her English and French. She also spent time at a village school, a writing school in Edinburgh, a dance school and Nasmyth’s Academy.

Back home she collected shells (later donated to Somerville College) and devoured books, a pastime some of her family disapproved of, regarding it as 'unfeminine' to read so much.

While some looked down their noses, her uncle Dr Somerville was encouraging, introducing her to men of science and providing access to his own scientific and philosophical library.

Mary was also strongly political. As a child she gave up sugar in protest against slavery and she later became a keen advocate of women’s education and suffrage.

In 1804 she met her first husband, Captain Samuel Greig. He was opposed to 'female learning' and although he allowed her to pursue her interests he also discouraged her.

When he died in 1807, he left her with two young children and an inheritance sufficient to allow her to study in earnest.

She threw herself into these studies and when confident began testing out her understanding by sending in solutions to mathematical puzzles (under the pseudonym “A lady”) to the Mathematical Repository.

In 1812 she married her cousin Dr William Somerville, who like his father (and unlike her first husband) supported and encouraged Mary’s pursuit of scientific and intellectual knowledge.

They moved to London and there mixed with many great figures from science and the arts. In 1826, at the age of 46, she published her first scientific paper on magnetism and the solar spectrum.

Not long after she was asked to translate Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Traité de mécanique céleste for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, a publishing project designed to give access to new ideas to the working and middle classes and tempt them away from radical politics.

The resulting book, Mechanism of the Heavens (1831) was not just a translation but a clarification of the ideas it contained. It made her and became a textbook for Cambridge undergraduates until the 1880s.

If looking for her impact on the world of astronomy, this would be it: her books helped shape the education and ways of thinking of several generations.

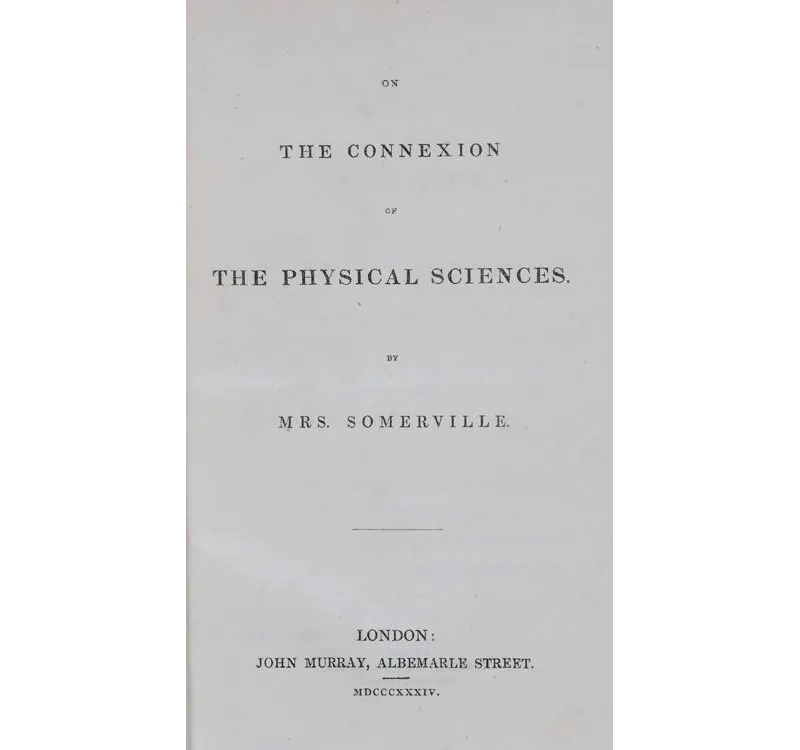

While her first book had been successful and well received, it was her second, On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences (1834) that cemented her reputation and became one of the best-selling science books of the 19th century.

In his anonymous review William Whewell noted that, given the ever developing and expanding nature of scientific enquiry, a new term was required for its practitioners, suggesting in his review the word ‘scientist’, which he coined in analogy with ‘artist’.

There followed awards and honorary memberships from societies around the world, including the Royal Astronomical Society, which broke with tradition to make Mary Somerville and Caroline Herschel their joint first female honorary members in 1835.

From around the time of her second book, until her death in 1872, Mary and her husband lived mainly in Italy. There, she published two more books.

Her two surviving daughters went with them, caring for their mother in her old age. In 1874 her collected letters were published (around the same time as Caroline Herschel’s).

Her obituary in The Morning Post declared Mary Somerville to be ‘the queen of science’.

Mary Somerville's published works

1

Mechanism of the Heavens (1831)

Somerville's first book was used as a textbook to teach University of Cambridge undergraduates.

2

On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences (1834)

Her second book became one of the best-selling science textbooks of the 19th-century before Charles Darwin.

3

Physical Geography (1848)

Somerville's next book was the first English textbook on its subject-matter. It was used in universities for decades.

4

Molecular and Microscopic Science (1869)

This was a commercial success but was regretted by Somerville who wished she had spent more time on her true passion: mathematics.

Dr Emily Winterburn is author of The Quiet Revolution of Caroline Herschel: The Lost Heroine of Astronomy.

This biography originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.