At times our ignorance about the Universe around us is breathtaking. Often I realise that a fact that I’d taken for granted is being called into question.

The identity of the closest star to the Sun, for example, and the length of the day on Saturn are both up for debate.

More amazing Chandra observations

On larger scales, we don’t really have a satisfactory measure of our own Galaxy’s mass. Indeed, how do you measure the mass of the Milky Way?

Weighing the Milky Way is an exercise in more than just idle curiosity, too.

Studying our Galaxy is one way that cosmologists test their ideas about how still-mysterious dark matter shapes the formation of galaxies.

One particular problem is that our home system seems to have too few satellite galaxies in orbit around it, a problem that goes away if we have a Milky Way which is less massive than expected because lighter central galaxies have a less populated retinue.

Those dwarf galaxies we do have are a little unexpected in themselves. They turn up in odd places, preferring to sit above the Galaxy’s poles than along its disc, and more of them seem to have ceased substantial star formation than in similar systems we see elsewhere.

Turning to ESA's Gaia satellite for help

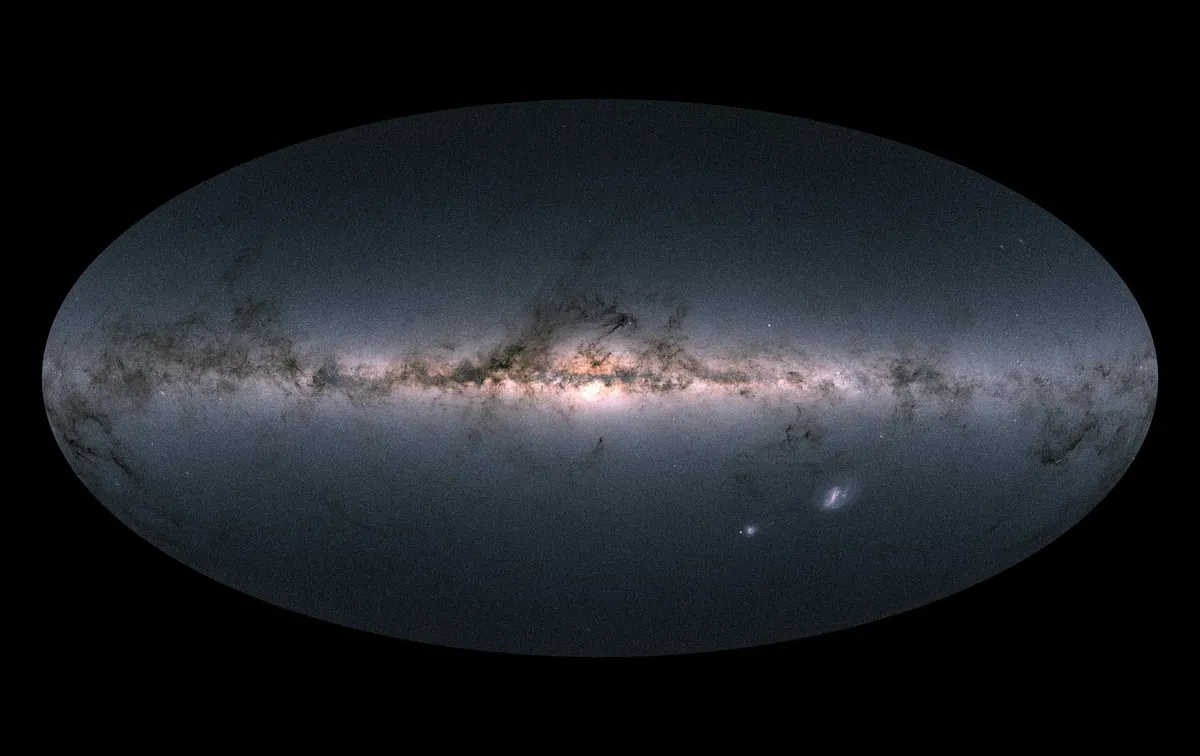

The opportunity to see whether these mysteries can be resolved by sorting out the Milky Way’s mass comes from a data release from ESA’s Gaia satellite, which has mapped and recorded the movements of nearly two billion stars.

Though the bulk of the data describes stars within our Galaxy’s main disc, enough have been identified in satellite galaxies that the team behind a new paper have been able to work out how these miniature systems are moving in relation to the Milky Way.

Because their motion is controlled by the pull of the Milky Way’s gravity, watching the satellites move, and comparing those movements to the esoterically named Phat ELVIS suite of simulated galaxies, gives us a measure of mass.

In contrast to methods that involve counting stars, because we’re measuring the effect of gravity itself we get a value for the total mass, including both normal baryonic matter and that pesky dark matter.

In practice, the team are comparing properties of the galaxy population, such as the speed in which satellites are moving towards or away from the Milky Way.

In an ideal world they’d be able to measure the time since each satellite first entered the Milky Way halo.

Unfortunately, that’s best determined by travelling back in time, and as the team note that they lack a Back to the Future-style DeLorean, they can’t compare this value with simulations.

Nonetheless, the results look convincing, with the Milky Way weighing between 1 and 1.2 trillion solar masses.That’s high enough that the missing satellite problem still exists.

Future surveys, including that carried out by the Vera Rubin Observatory (now under construction in the Atacama desert), should expect to detect more small companions of the Milky Way, each of which will ease the worries of cosmologists and, as a bonus, add to our ability to measure the mass of the Galaxy we call home.

Chris Lintott was reading Sizing from the Smallest Scales: The Mass of the Milky Wayby MK Rodriguez Wimberly et al. Read it online at arxiv.org.