The giant star-forming region known as the Lagoon Nebula, situated perhaps 5,000 lightyears from Earth, is a fascinating place for learning more about stars and how they form

The bright Lagoon Nebula harbours stars that are only now forming, alongside some brilliant examples of young, massive stars whose influence shapes the nebula itself.

Trying to disentangle what is clearly a complex history has kept astronomers busy for centuries.

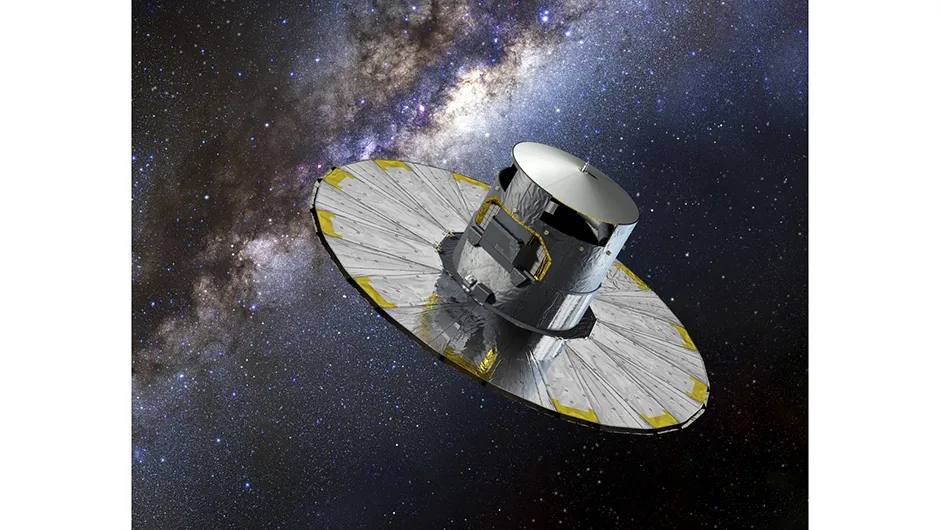

A team of astronomers used data from ESA’s celestial cartographer, Gaia, to take a close look at the stars embedded in the nebula’s gas.

The nice thing about the maps produced by Gaia is that they show how stars move, as well as where they are.

But as we should expect from the Lagoon, this only adds to the complexity.

For starters, it turns out there are two separate clusters rather than just one, each expanding slowly.

The first covers the whole of the nebula, while the second is concentrated in its western lobe; its presence probably reflects a second, distinct phase of star formation in the nebula’s complex past.

Leaving the geography aside, the researchers are focused on thinking about how the stars move, measurements which can give us a clue into how clusters of stars like this form.

The problem with star formation

We know that stars begin to form when a cloud of gas collapses under its own gravity, but we don’t know how fast this happens.

The speed of the collapse has implications for understanding what stars can form.

However, as we can’t sit and watch for the few million years it might take, it’s hard to measure.

This is where the velocity of the stars comes in.

If the cloud collapses quickly, any forming protostars fall into its gravitational well, heading for the centre of the new cluster.

This process alters their speed; some will speed up and some slow down, in a process confusingly known as ‘violent relaxation’.

The process doesn’t care about the mass of the stars, so we shouldn’t see any distinction between the velocities of stars of different masses.

If the collapse is slow, other factors become important.

Then, stars might be able to encounter each other as they fall towards the centre and such near-collisions will tend to send the less massive partner out towards the outskirts of the cluster.

We’ll then see low-mass stars spread all over and massive stars clustered in the centre, moving at a greater range of speeds.

Gaia seems to show that this isn’t the case in the Lagoon.

We have stars of all masses sharing velocities, just as one would expect from violent relaxation and nothing else.

That in turn means rapid collapse and that the Lagoon, at least, is a place where stars are made efficiently.

With similar measurements of stars in the Orion Nebula recently released, maybe we’re seeing evidence that that’s true throughout the Milky Way.

Chris Lintott was reading Unveiling Two Expanding Stellar Groups formed through Violent Relaxation in the Lagoon Nebula Cluster by A Bonilla-Barroso et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2403.00247.

This article appeared in the May 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine