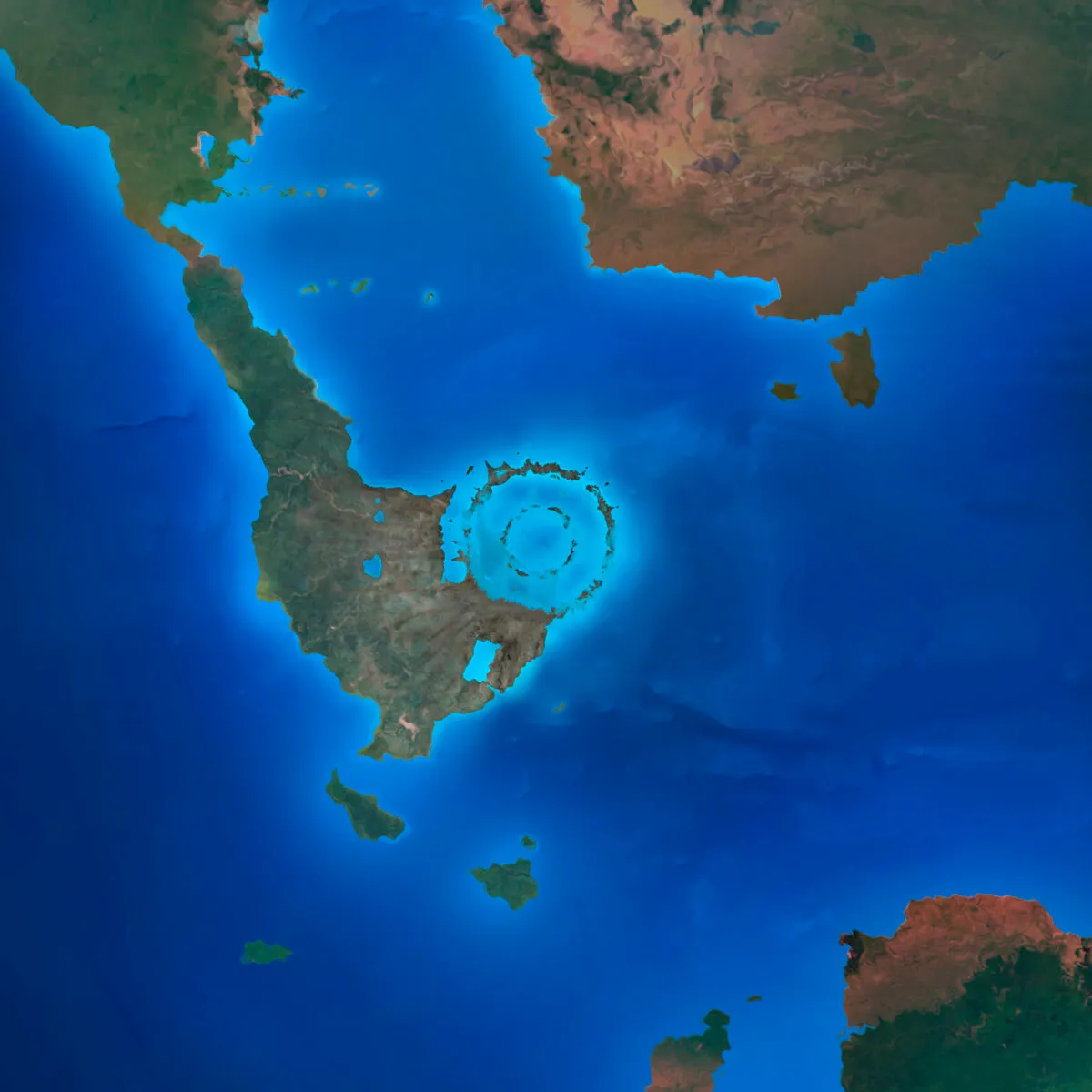

The Nadir crater is a 9km-wide (6-mile) impact crater on the Guinea Plateau off the west coast of Africa, a scar left by an asteroid or comet impact on Earth.

Nadir’s impact occurred into an ocean, affecting the crater’s shape, and scientists think it occurred around 66 million years ago, at the same time as the Chicxulub impact that killed off the dinosaurs.

To find out more about its discovery we spoke to Veronica Bray, a planetary scientist from the University of Arizona who uses computer modelling and theoretical analysis to understand impact craters.

What was the Chicxulub impact?

It’s believed that a massive asteroid impact 66 million years ago killed around 75% of life on Earth, including the dinosaurs.

It formed the Chicxulub crater on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico.

Compared to Nadir’s 9km diameter, Chicxulub is around 200km (124 miles) across. When the asteroid that formed Nadir hit, it would have caused local devastation.

For Chicxulub, the devastation was global. It would have ejected so much rock ash into the atmosphere that it would have assisted the cooling of Earth for years.

Super-hot ejected material would have rained down, heating Earth’s surface, while dust from the crater would blot out the Sun, leading to freezing global conditions.

It was the resulting long-term changes to Earth’s climate that eventually allowed warm-blooded creatures to take their place at the top of the food chain.

How did you study the Nadir crater?

Our research involved modelling the full structure of an impact crater.

On other planets and moons, we can only see the top of a crater, so we don’t have any idea about the subsurface.

On Earth, it’s usually the opposite: the crater’s surface is eroded or covered, but we have seismic data to give us an idea of its structure.

Luckily, we have high-resolution seismic data about Nadir crater, initially taken for oil and gas prospecting.

Is Nadir an impact crater?

By simulating different impacts, we showed that Nadir has the properties expected for a marine impact crater.

To further confirm this, we need to find physical evidence of a tremendous shock in Earth’s surface by drilling into Nadir and looking at the rocks.

If it is an impact crater, we expect to find rock textures left over from the passage of a shockwave.

In shocked quartz, for example, you get crisscrossing features which only form at extremely high pressures.

These pressures can also melt or vaporise rock, so melted rocks are another indicator.

What makes Nadir unique?

There are only about 200 impact craters that we know of on Earth, and many of them are eroded or buried by plate tectonics and active weather.

Nadir is buried under sediment, so has been preserved.

By studying Nadir, we can learn about the impact that caused it, the devastation that followed and its potential relationship to the Chicxulub impact.

Did Chicxulub and Nadir happen around the same time?

When we collected 3D seismic data of Nadir, some samples of the rock cores were collected.

In these rock samples, the deeper layers are the oldest rocks, so can be linked to different ages in Earth’s history.

From that, we could work out the general age of the crater. If we can drill into the crater, we can more accurately determine the crater’s age throug a process called radiometric dating.

What can the craters tell us about the relationship between the impacts?

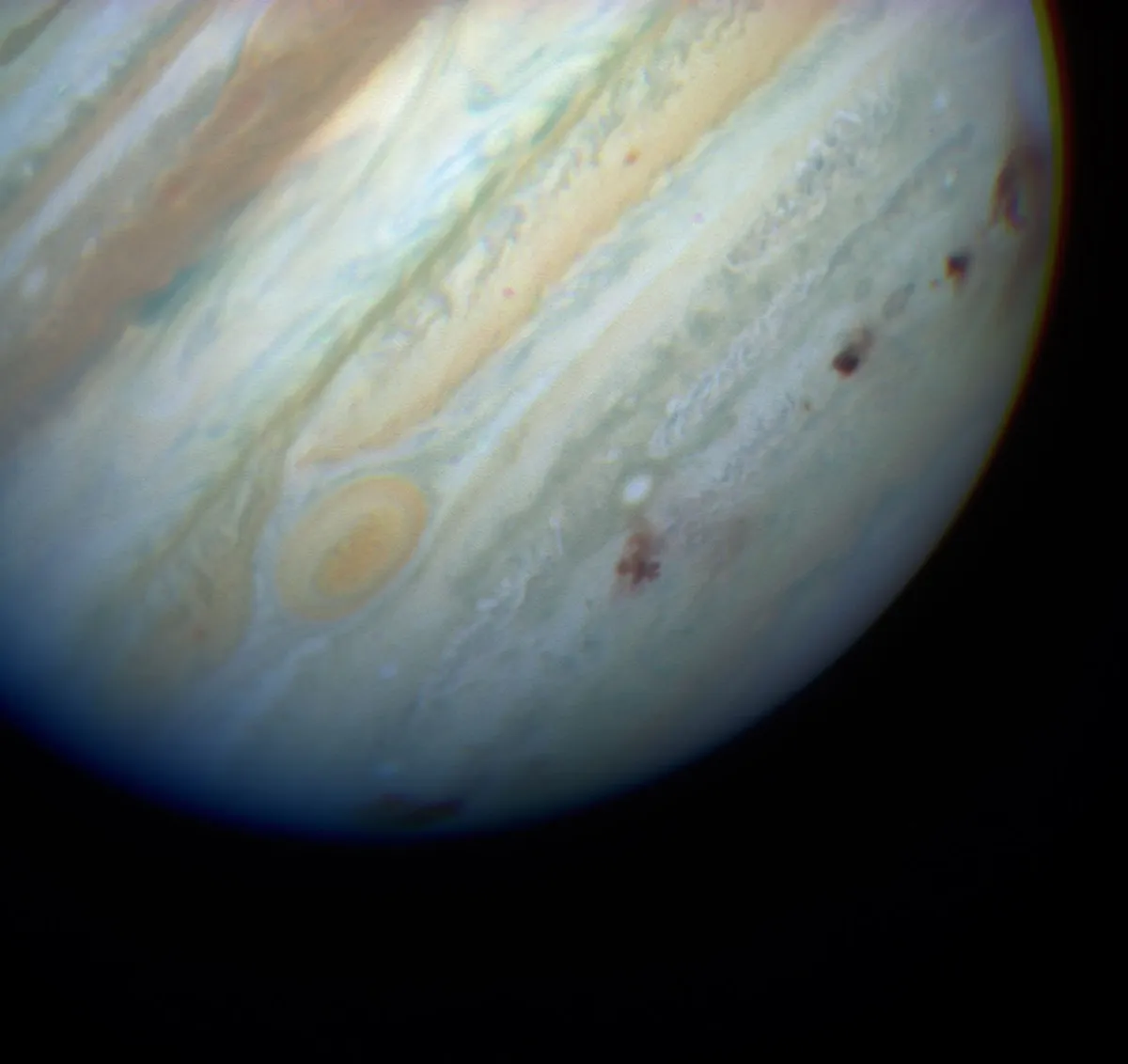

In 1994, comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 passed by Jupiter. It started as one body, but was tidally disrupted and broke into fragments.

The remaining fragments were tidally disrupted and pulled apart from one another.

When the impacts of these comets occurred, they did so in a line. A similar thing might have happened with Nadir and Chicxulub.

We know from Martian crater studies that the larger chunk of an asteroid will go the furthest and, before that, you get smaller craters formed by smaller chunks of asteroid.

The three-dimensional data about Nadir’s shape tells us about the asteroid’s trajectory. We would expect this impact trajectory to point towards Chicxulub, and it does.

This interview appeared in the December 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine