NASA's Juno spacecraft has captured views of Jupiter's moon Io - the most volcanic body in the Solar System - showing a mountain and a smooth lake of cooling lava.

The views were produced by members of the Juno team, who created animations using data collected by Juno's flybys of Io in December 2023 and February 2024.

Find out about moon Io's collapsing atmosphere

During the flybys, Juno flew within about 930 miles (1,500 kilometres) of Io's surface and captured the first ever close-up images of the Jovian moon's northern latitudes.

"Io is simply littered with volcanoes, and we caught a few of them in action," says Juno’s principal investigator Scott Bolton.

"We also got some great close-ups and other data on a 200-kilometre-long (127-mile-long) lava lake called Loki Patera."

"There is amazing detail showing these crazy islands embedded in the middle of a potentially magma lake rimmed with hot lava.

"The specular reflection our instruments recorded of the lake suggests parts of Io’s surface are as smooth as glass, reminiscent of volcanically created obsidian glass on Earth."

Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) also revealed that Io has a surface relatively smooth compared to the rest of Jupiter's Galilean moons and has poles that are colder than its middle latitudes.

During Juno’s most recent flyby of Io, on 9 April, it came within about 10,250 miles (16,500 kilometres) of the surface. It will begin its 61st flyby of Jupiter on 12 May 2024.

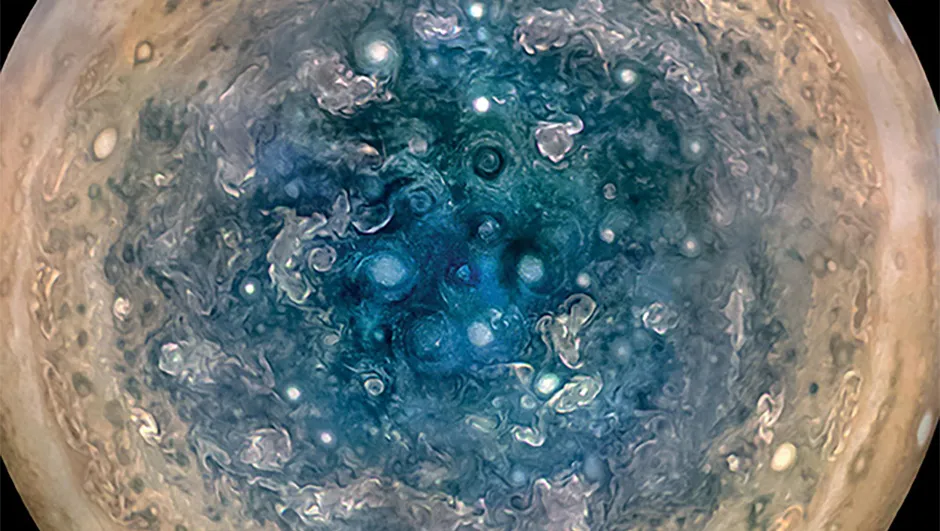

Jupiter's cyclone storms

Other recent data collected by the Juno spacecraft pertains to Jupiter's northern polar cyclones.

These swirling storms are studied in greater detail by Juno as it flies closer to the north pole of Jupiter during each polar orbit.

Data shows that the polar cyclones are a range of sizes and structures.

"Perhaps most striking example of this disparity can be found with the central cyclone at Jupiter’s north pole," says Steve Levin, Juno’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

"It is clearly visible in both infrared and visible light images, but its microwave signature is nowhere near as strong as other nearby storms.

"This tells us that its subsurface structure must be very different from these other cyclones.

"The MWR team continues to collect more and better microwave data with every orbit, so we anticipate developing a more detailed 3D map of these intriguing polar storms."