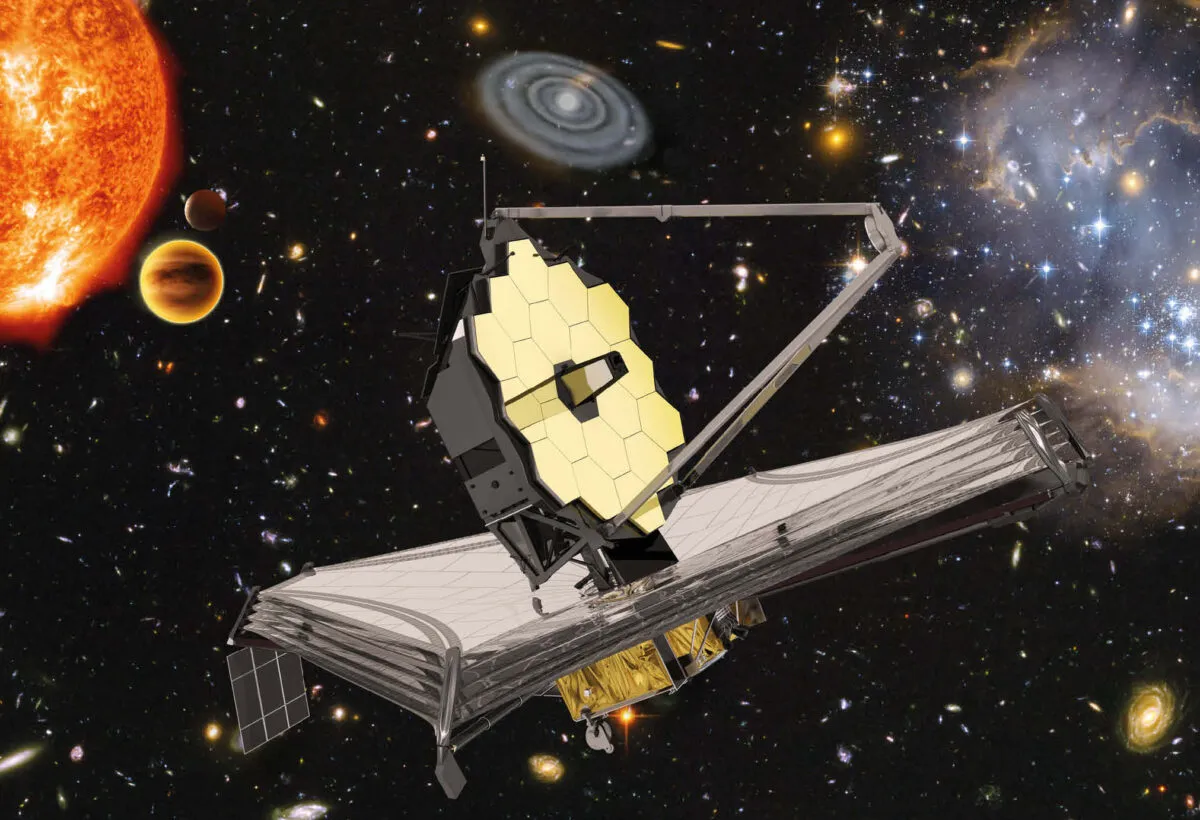

With a mirror area 64 times bigger than NASA’s previous infrared space telescope and instruments up to 100 times more sensitive, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is allowing us to take deeper and sharper images of astronomical objects than ever before.

Although JWST is a NASA-led mission with involvement from the European and Canadian space agencies, astronomers from any country can apply for observing time.

When the call for proposals went out in 2018, I decided to request observations of Supernova 1987A.

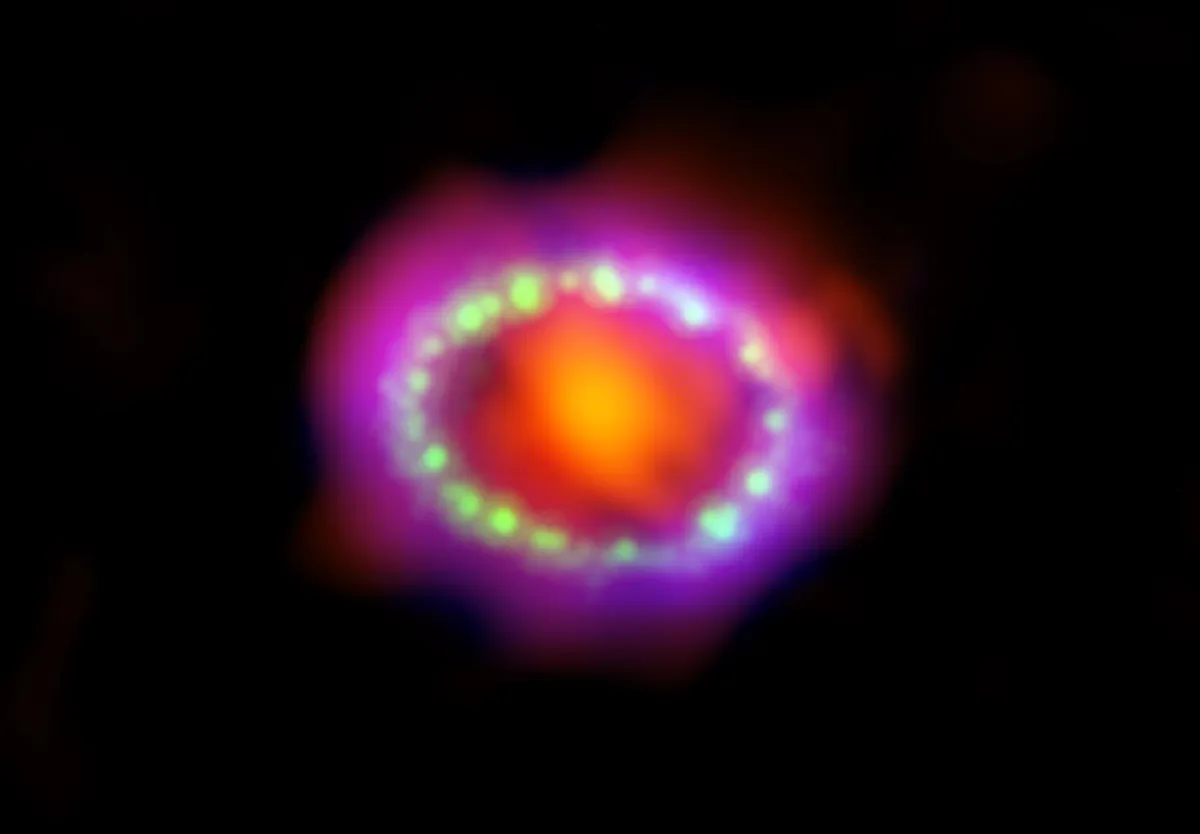

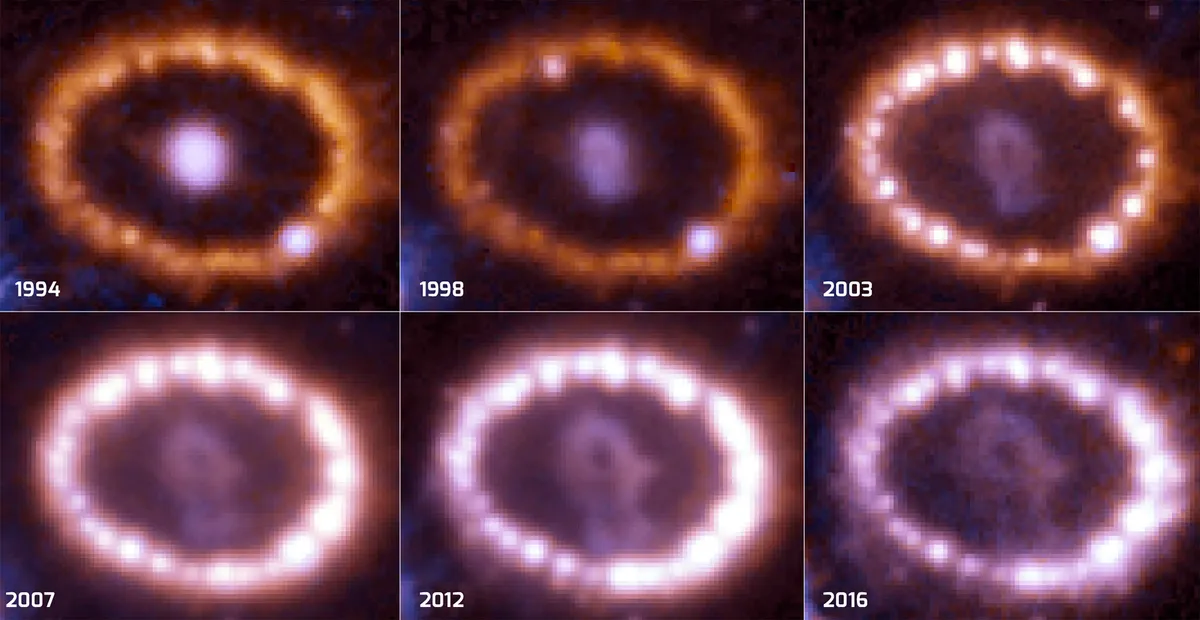

It’s the closest supernova explosion in the last 400 years, located 170,000 lightyears away from Earth.

We’ve been able to see the fast shock waves from the supernova, travelling at 1,000km/s, as they expand and destroy the surrounding material.

Writing an observing proposal is time-consuming. It takes up to two weeks, requiring detailed simulations of how much time is needed.

But just as I finished writing the proposal and went to click the submit button, an e-mail from NASA arrived announcing the launch was delayed.

How disappointing! JWST is a $10bn space mission, so of course it’s better to be safe than sorry. But still, it was disheartening.

NASA reopened proposals two years later. When I looked back at my work, I realised it lacked a punchline: “Why do we need the JWST for this observation?”

It’s a key point that should be included in any observing proposals, but it was missing. I realised JWST will be able to capture how blast shock waves break up dust, which we couldn’t see before.

Meeting the JWST deadline

Then, three days before the deadline, when everything was sorted, I realised something was wrong in my exposure time simulation.

I started panicking, but it’s always helpful to have collaborators.

My colleagues Tea Temim and Martha Boyer from the Space Telescope Science Institute redid the simulations from scratch and we were able to submit on time.

Back in 2018, I’d also wanted to observe planetary nebula NGC 6302, but it would have been far too demanding to write two proposals.

However, as I’d done most of the work for the Supernova 1987A submission back in 2018, I was able to write a new proposal for NGC 6302 - also known as the Butterfly Nebula - in 2020.

It is always good to share ideas and get constructive criticism, and when I did, Rens Waters from Groningen and Eric Lagadec from Nice said "It‘s a good idea, but there are too many details".

Sometimes if you are in your own world, you don’t really see your own faults: you lose the bigger picture.

Rens re-wrote the first key introduction paragraph, guiding the scientific case, and so the second proposal was submitted.

Another six months passed. It was April 2021, a sunny day just before Easter.

My husband and I took an extra day off and went for a drive when suddenly my phone notified me the JWST selection results were out.

I was so scared to open the emails, not knowing if they would say "Congratulations!" or "We’re very sorry".

After I came back home, I took a breath and opened them. Both were accepted. Unbelievable!

At the same time, the responsibility to make these observing programs successful now fell on my shoulders.

And now, as the data arrives, it’s time for the next round of challenges to begin.

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.