Just how special is our Blue Planet? How many other planets in the Solar System have liquid water on their surface? It’s a question that continues to vex astronomers as they scour the cosmos for habitats that might support life.

Certainly among the worlds within our Solar System, Earth has one feature that clearly stands out: ours is the only one to have a surface covered in liquid water.

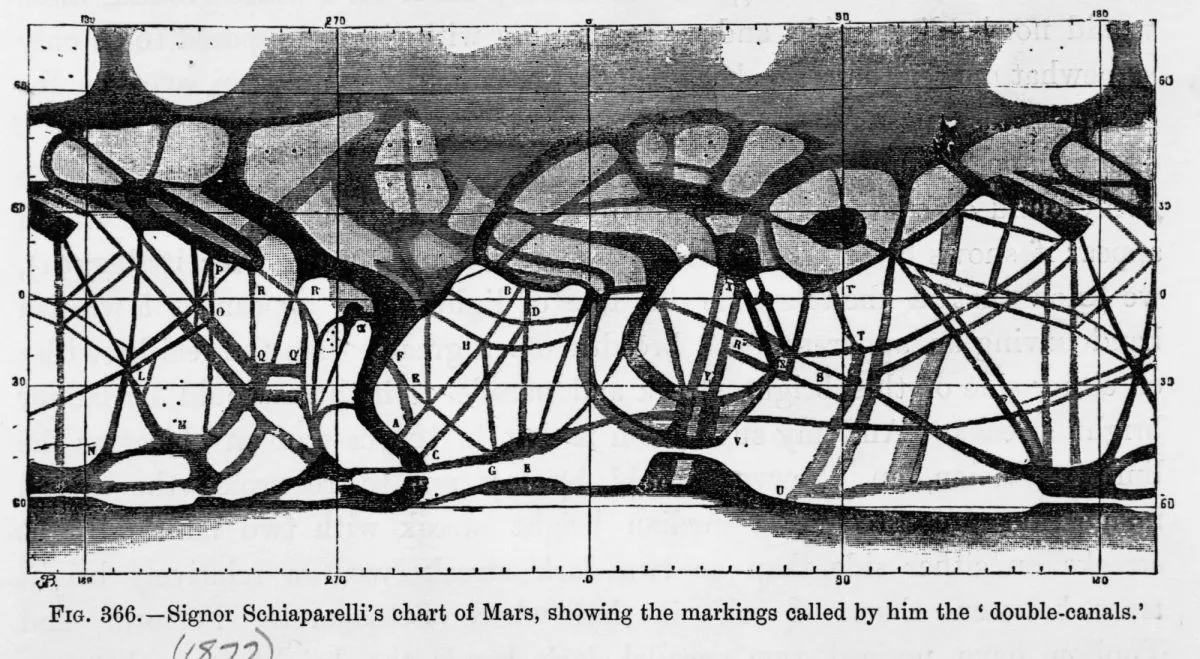

Prior to the space probes of the 1960s, it was thought that Mars and Venus also had water, that the Red Planet had canals and that a tropical paradise lurked beneath the dense clouds of ‘Earth’s twin’.

More about the Solar System:

- A guide to the rings of Saturn

- How astronomers estimate the ages of planetary surfaces

- Why we should send a spacecraft to explore Uranus

By the middle of that decade both had been proved to be wishful thinking, and though there is evidence that water once flowed on each of them – much more so for Mars than for Venus – whatever surface seas might have existed are now long gone.

Water is, nonetheless, surprisingly common throughout the Solar System: as ice, as gas, possibly even in a ‘supercritical’ state

For decades our cosmic backyard appeared to mimic that of the most famous lines from the Rime of Ancient Mariner: ‘Water water everywhere, nor any drop to drink’.

Water in abundance, it seemed, except as a liquid, the form essential for life as we know it.

But since then planetary science has uncovered evidence of liquid oceans out there after all, not at surface level, but gently sloshing just below the crusts of a handful of dwarf planets and moons.

The most famous candidates are on Jupiter and Saturn's moons Europa and Enceladus, respectively, but there are at least nine worlds that could have subsurface seas within exploring distance.

5 Solar System bodies that host water

Enceladus

This Saturnian moon is famed for its giant geysers, the jets of water vapour that erupt into space through a set of ‘tiger stripe’ fractures near its south pole, and which were explored by the Cassini mission.

Since their discovery in 2005, we’ve learnt that the water is salty, that the jets contain a smattering of organic compounds, and that the material unleashed feeds Saturn’s E-Ring.

Gravitational anomalies have also led scientists to believe there is a 10km-deep ocean in this region, and that it could be larger than the greatest of North America’s Great Lakes.

Moreover, it is thought to be warm and in direct contact with the underlying silicate rock, meaning that it could contain the essential compounds needed for life to thrive.

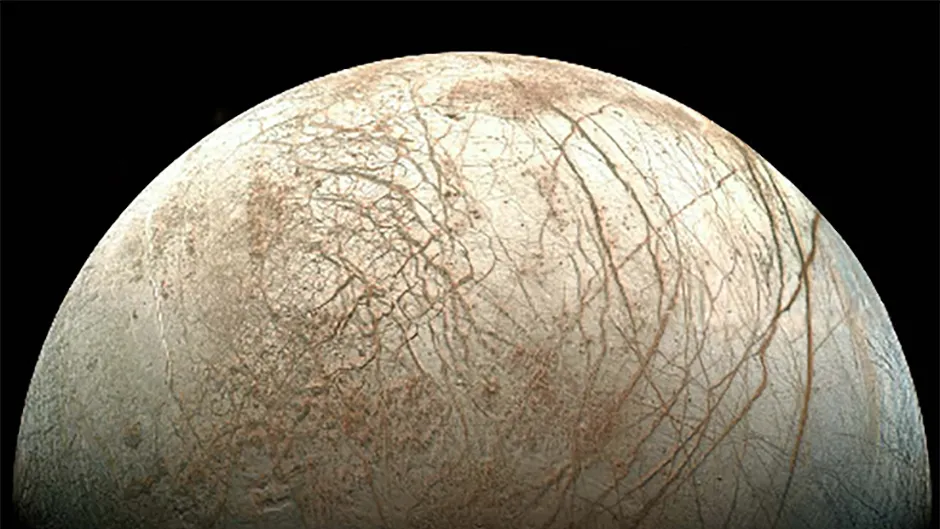

Europa

Though primarily rocky, the smallest of the Galilean moons is also believed to have a global saltwater ocean beneath its icy crust, again in direct contact with mineral-rich rock.

Jupiter exerts strong tidal forces on Europa, and these are thought to both generate the heat that prevents the ocean from freezing solid and flex the icy crust to the point that it splinters, creating the long cracks that streak across the moon’s surface.

It has also been suggested that the dark material that coats these fissures could be sea salt that has been discoloured by radiation.

Planetary scientists hope to learn more about this promising icy moon when the Europa Clipper spacecraft begins studying it.

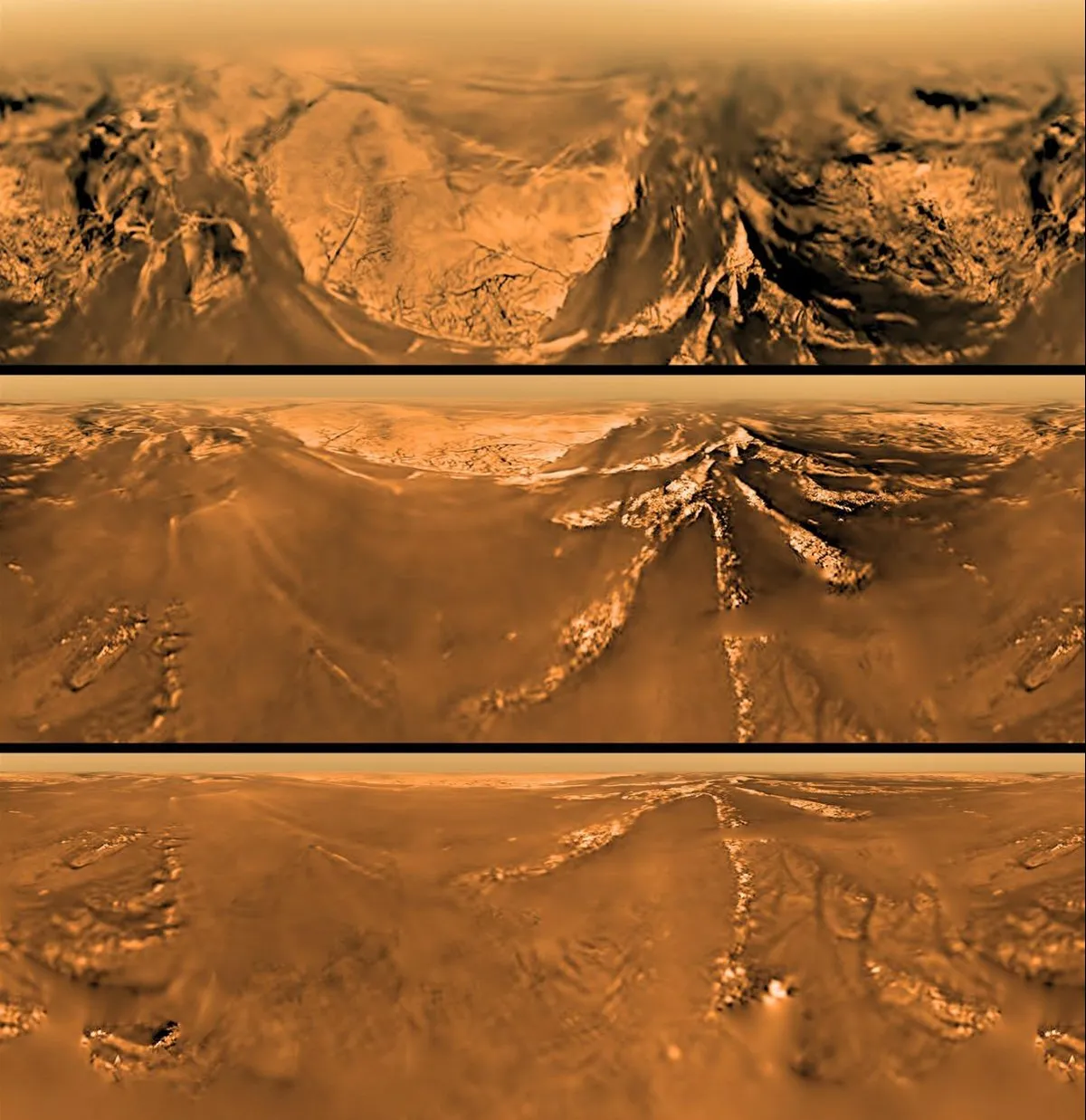

Titan

Saturn’s largest Moon is already famous for its lakes, albeit ones of methane, but it may also have a global underground ocean as salty as the Dead Sea.

Unlike Europa and Enceladus, however, astronomers think that Titan’s ocean sits above another layer of ice.

Variations in the thickness of Titan’s icy crust suggest the briny body beneath may be in the process of freezing.

The Huygens probe - part of the Cassini mission - landed on Titan in 2005 and returned incredible images of its surface.

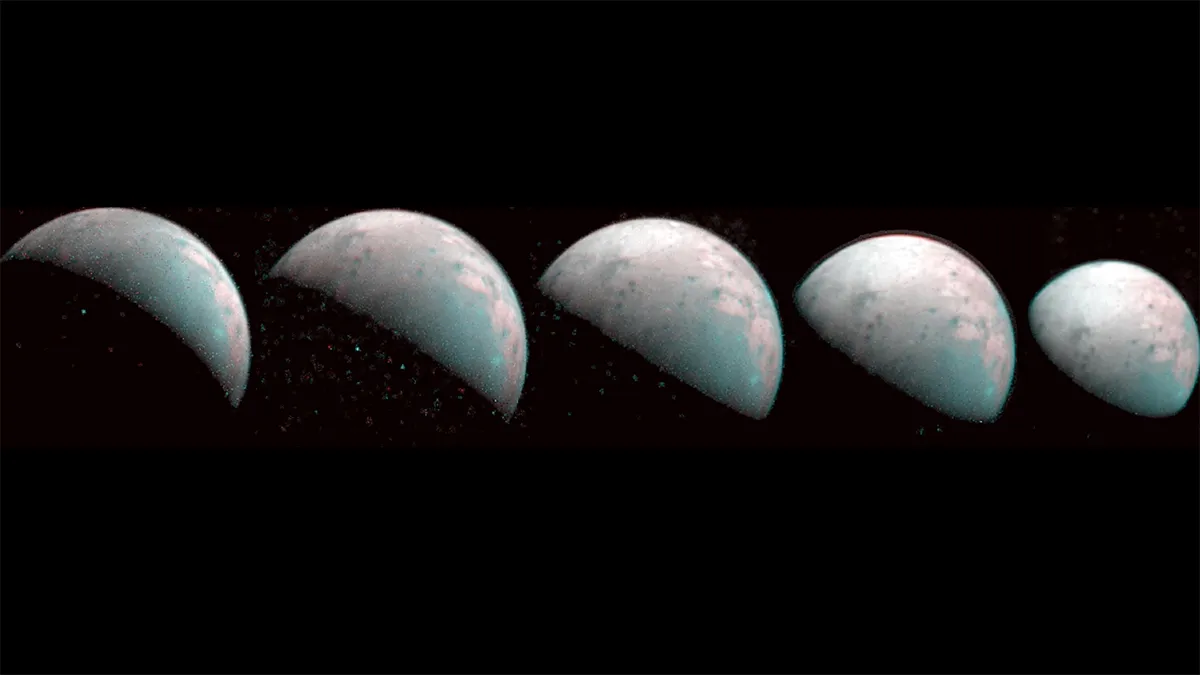

Ganymede

Evidence for a subsurface ocean on Ganymede comes from an unlikely source: discrepancies in the way the Jovian moon’s aurora ‘rocks’ in response to magnetic fields.

The global saltwater ocean inferred to exist as a result is likely to be huge, containing more water than exists on Earth’s surface.

It is possible this ocean is arranged as a ‘sandwich’ of several layers of water interspersed with seams of ice.

Suspect seas

Five more worlds could possibly possess underground oceans. Electrical currents detected by the Galileo probe suggest that cratered Callisto may be the third Galilean moon where life could exist; a saltwater ocean could act as the conductor.

Saturn’s ‘Death Star’ moon Mimas shows an unusual wobble in its orbit – too large for its diminutive stature – that could be caused by a hidden body of water.

The final candidate moon is Neptune’s largest, Triton, which is thought to be a captured Kuiper Belt object.

It’s possible that the huge gravitational forces Triton would have sustained on its capture could have resulted in an ocean.

The Trident mission was set to study Triton up-close, but wasn't given the go-ahead.

This guide originally appeared in the July 2015 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.