How do you monitor penguin colonies in the Antarctic? One way is to use a satellite to search for penguin poo, and that's exactly what a school science club from the UK has been doing.

Pupils from Stirling High School in Scotland used data from the European Space Agency's Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite to study Emperor penguins and their poo, and ended up discovering 11 new colonies.

Dr Andrew McDonald is a physics teacher at Stirling High School and a former Earth observation scientist with the British Geological Survey.

We spoke to Dr McDonald to find out more.

How did pupils at Stirling High School become involved in a satellite study of penguins?

I was watching a David Attenborough programme where he was in Antarctica looking at various penguin colonies and he explained that they had been monitored using aerial photography.

It got me thinking about whether it would be possible to monitor them from space, given the higher resolution of some of the new satellites. I came back to my small group of researchers, aged roughly 11 to 15, and we batted the idea around.

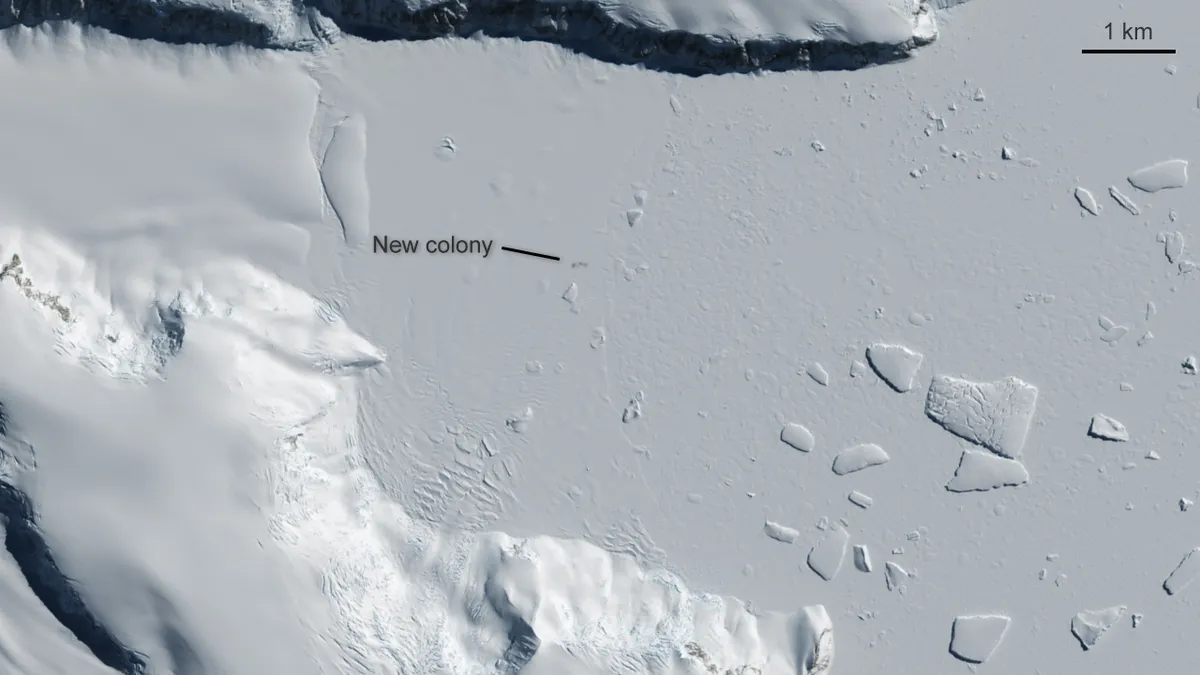

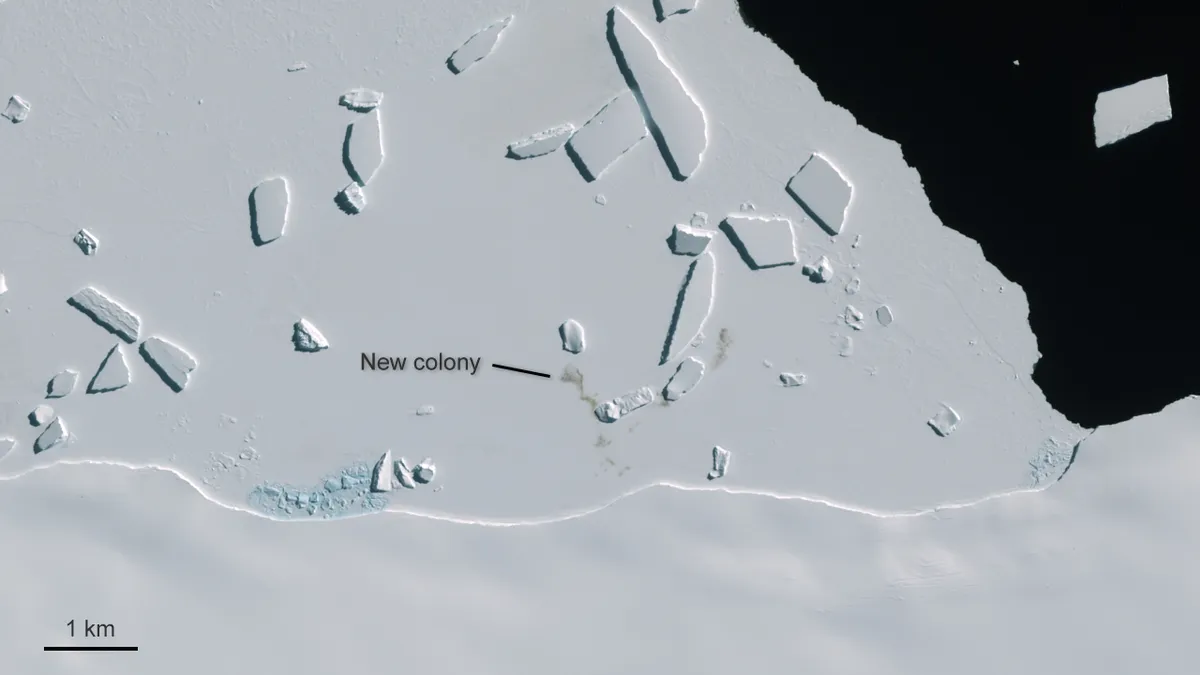

We looked at satellite data from the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-2, which gives us about a 20m square pixel on the ground. It’s not super high resolution, but it’s a lot better than previous satellites.

Sentinel-2 also gives a range of wavebands, from the visible to short-wave infrared (SWIR).

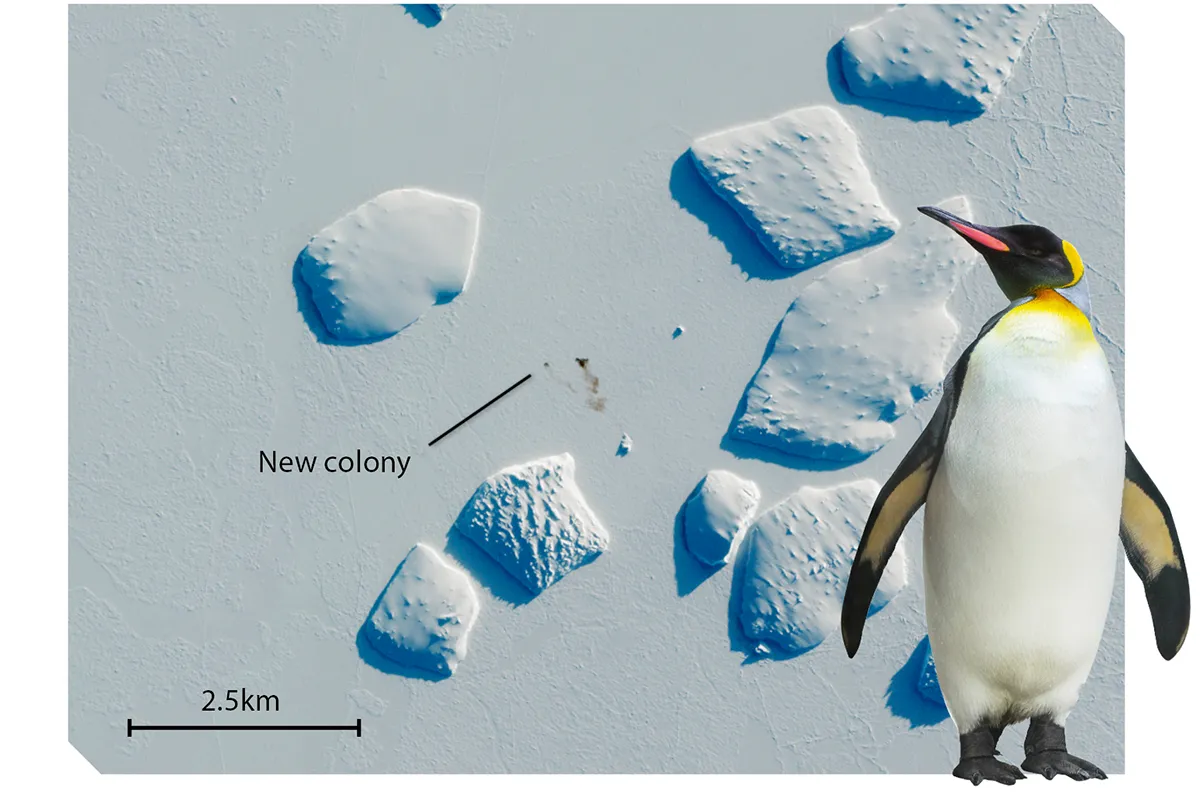

To help us find the colonies we looked for the guano (accumulated excrement). Having located the known colonies, we then looked at variations in the different wavebands to come up with a way of processing the imagery to best highlight penguin poo.

What does penguin poo look like from space?

The guano is a dark splodge against the icy background – effectively a dark brown stain.

It changes through the breeding season so you can use it to track the movement of the penguins from one area to another.

We found that we could improve on that even more by looking at the SWIR data, which gives a better resolution and therefore a better idea of the colony’s boundary and where it actually is.

How did pupils use Sentinel-2 data to find penguins?

The pupils came together as the Researchers in Schools Club (RISC), run in conjunction with the charity Institute for Research in Schools (IRIS).

The idea is that it doesn’t matter how young you are, you can still do real scientific research. It is an extracurricular club: my pupils did everything at lunchtime or in their own time.

We used the Sentinel Hub, which is free and open to everybody. As well as an Earth Observation browser, you can access data from different satellites.

Some pupils worked out the coding script to do our guano detection, while others looked at multi-temporal images (images over time) that might be for different years, or within a single breeding season.

We did this for known colonies, but it raised the question of whether this technique could be applied to look for other colonies; that’s what the British Antarctic Survey did.

How did your school club’s work inspire British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists?

Within our research, BAS scientist Dr Peter Fretwell’s name came up, so we emailed him. He kindly provided us with additional information about known penguin colonies and some of the work they had done.

On the basis of that we could then go ahead with our research and we bounced results back to him.

When his paper with Dr Philip Trahan came out with the acknowledgement that we’d inspired him to do more – that was such a great boost for the RISC team.

It was an absolute surprise. I downloaded the paper and I was thrilled on behalf of the pupils.

What did the BAS study show?

They identified a number of known colonies, but they also confirmed 11 new colonies (meaning there are 20% more colonies than previously known). That’s a big deal because penguins are a good indicator species for climate change.

How can educators inspire young people in space or astronomy?

The best thing we can do is be enthusiastic, as the curriculum can be a little bit dry. It’s about taking it away from just saying "Okay we are doing rotational motion".

We can do that just as theory, or we can say "Let’s have a look at what that means for satellites in orbit" and broaden it out to give context.

Dr Andrew McDonald is a physics teacher at Stirling High School and is a former Earth observation scientist with the British Geological Survey. He is also a lead educator for the UK’s National Space Academy.

This interview originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.