There’s something strange about the star WISEA J080822.18-644357.3. And it’s not just the star’s extreme mouthful of a name. J0808 is an M-class, low-mass red dwarf star in the Carina association, over 330 lightyears away.

It exhibits an extreme infrared excess – this means that the J0808 system is giving off far more thermal energy than you would expect from its visible brightness.

The normal reason for this is that newly formed stars are often still surrounded by a protoplanetary disc of gas and dust, which warms up in the young starlight and emits the extra infrared radiation.

The strange thing is that J0808 isn’t really all that young. It formed about 45 million years ago.

Read more from Lewis Dartnell:

- Is electric propulsion the future of spaceflight?

- How do binary asteroids form?

- Can an exomoon make plants grow?

It was previously thought that any primordial disc of gas and dust, or a secondary debris disc created during the later stages of planetary formation, ought to have long since dispersed by this time.

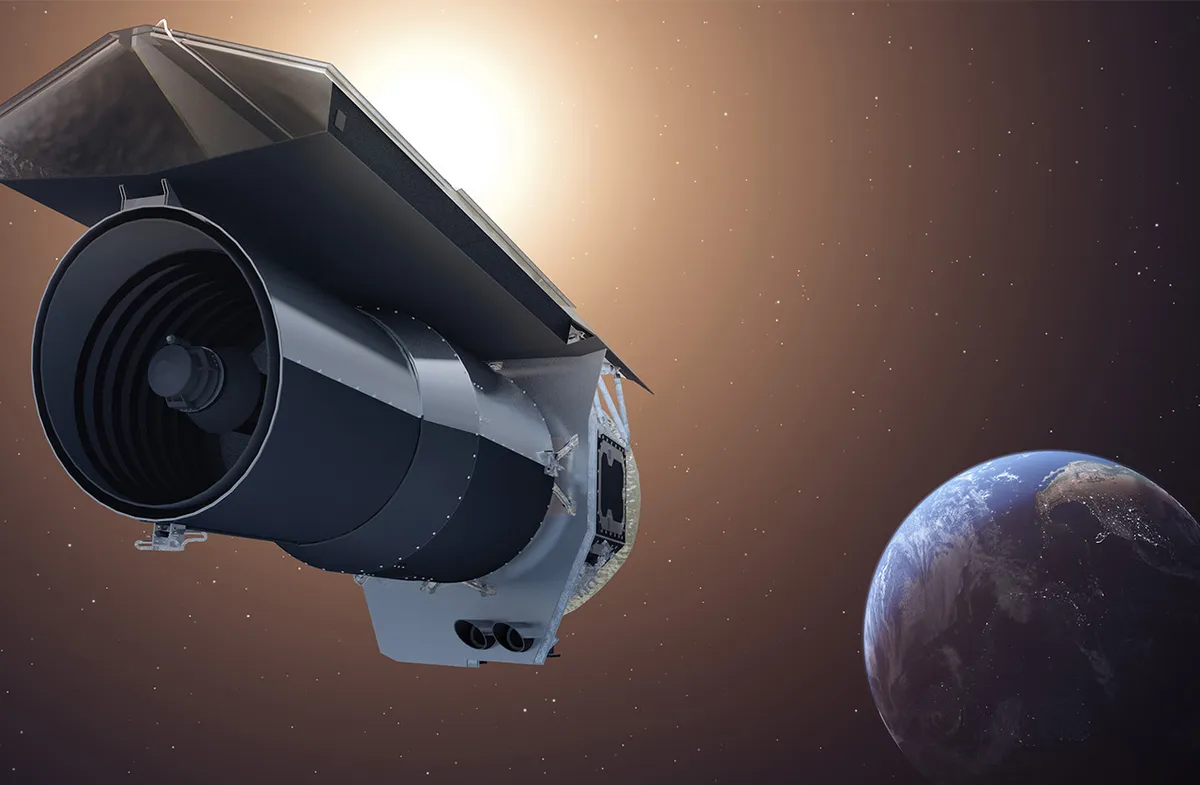

For example, a Spitzer Space Telescope survey of almost 200 newly formed stars didn’t find a single one that still had a protoplanetary disc after 10 million years.

Steven Silverberg at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and his colleagues have dubbed such star systems that apparently refuse to grow up as ‘Peter Pan’ discs.

Delightfully, the researchers even formally cite the author of Peter Pan (1904), JM Barrie, in the paper.

J0808 had already been recognised as an oddity by its late infrared excess, but now Silverberg’s team report on a handful more examples of such Peter Pan discs.

They were able to find them with the help of an army of volunteer astronomers. These new Peter Pan systems were discovered by the Disk Detective project; a citizen science collaboration between NASA and Zooniverse, run by The Sky At Night’s very own Chris Lintott.

The citizen scientists inspect images of star-forming regions taken by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and indicate any circumstellar discs they think they can see.

These candidates undergo further investigation using data from other ground- and space-based telescopes – such as Gaia, TESS, and the Gemini Observatory – to determine their distance and age, and to perform spectroscopy.

The increasing number of Peter Pan disc discoveries may indicate that they’re actually relatively common, but a big mystery remains about why these systems are refusing to grow up?

Silverberg considers a number of different possible explanations that could account for these very late protoplanetary discs, including the possibility that we’re seeing dust from the outer system migrating in to the star and warming up, or perhaps we’re witnessing the cataclysmic aftermath of colliding protoplanets.

But the confusing thing is that – alongside the vast amounts of dust – these Peter Pan discs also seem to hold gas.

Perhaps the simplest explanation then, concludes Silverberg, is that for some reason these M-class red dwarf stars just don’t disperse their gas-rich protoplanetary discs as quickly as other stars.

And this is exciting, because it means we’ve still got something fundamental to understand about the development of red dwarf stars.

Prof Lewis Dartnell is an astrobiologist at the University of Westminster. Lewis Dartnellwas reading Peter Pan Discs: Long-lived Accretion Discs Around Young M Stars by Steven M Silverberg et al. Read it online here.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.