In Douglas Adams’s popular sci-fi series The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the wandering characters find their way to a mysterious world named Magrathea that was once at the centre of the custom planet-building industry.

In the story, Magrathea is described as an ancient planet orbiting around twin suns in the heart of the Horsehead Nebula.

But how common might such planets actually be in our Galaxy?

Gabriele Columba, a PhD student in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Padua, Italy, and his colleagues have been investigating.

The type of planetary system they’re interested in is an exoplanet orbiting a binary pair where both partners are white dwarfs – which they dub Magrathea worlds.

(Although, here they’re considering gas giants rather than the sort of terrestrial planet that features in Hitchhiker’s.)

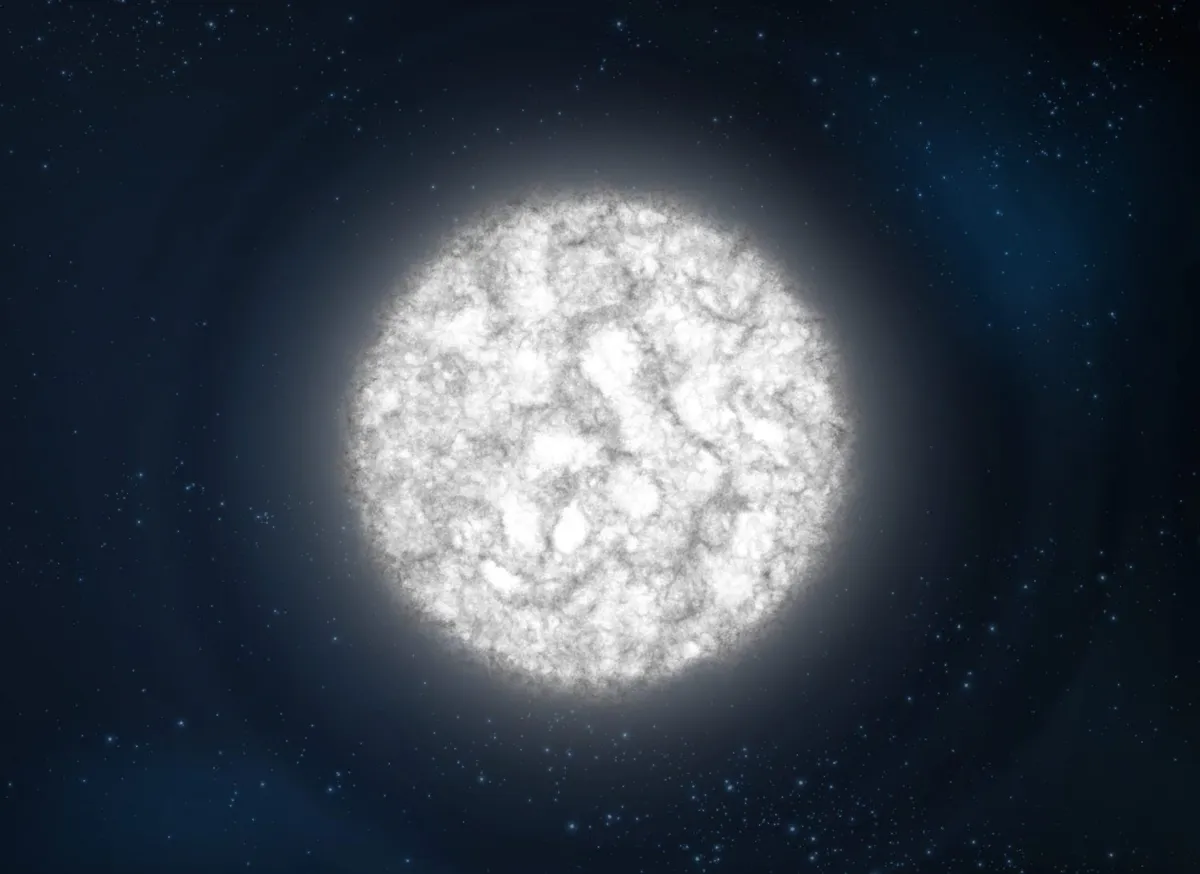

A white dwarf is the slowly-cooling remnant left behind after a star has reached the end of its lifetime on the main sequence, puffed up as a red giant and blown away a great deal of its outer gas layers.

The process the host stars undergo when they transform from main sequence to enormously inflated red giant, accompanied by a fierce solar wind, is certainly very disruptive for any planet orbiting them.

But some ought to be able to survive the ordeal, especially gas giants on wide orbits around the binary pair.

However, while a number of exoplanets have been discovered orbiting binary stars, and there is one confirmed planet orbiting a solitary white dwarf, we haven’t yet found a single example of a planet orbiting a binary pair of white dwarfs.

Is this because they’re rare, or more a consequence of the difficulty in detecting such exoplanets?

Columba and his team ran computer models simulating the life stages of the binary stars, from the main sequence, through red giant to white dwarf, and the effects these transformations have on a single orbiting gas giant.

Overall, they simulated over 20,000 different systems, varying the initial masses of the binary stars and orbital distance of the planet.

They ran each virtual planetary system until one of several possible outcomes occurred: the binary stars merged together, the planet collided with either star or was gravitationally ejected from the system, or survived for billions of years after both host stars had become white dwarfs – creating a Magrathea world.

Their results show that the formation of Magrathea worlds should actually be pretty common: 20–30% of the triplet systems they simulated ended up with a surviving planet around a double white dwarf, most often on a wide orbit.

They also found that of their modelled planetary systems which resulted in the planet on an unstable orbit, the planet was much more likely to become ejected from the system altogether rather than end up crashing into either of the binary stars.

And so such evolving binary star systems may represent a major source of free-floating planets in the Galaxy.

This is important work in preparation for the upcoming Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission, which is expected to discover tens of thousands of white dwarf binaries – and hopefully the first example of a ‘Magrathea’ exoplanet orbiting them.

Lewis Dartnellwas reading Statistics of Magrathea Exoplanets beyond the Main Sequence by Gabriele Columba et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2305.07057.

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

Click here to read about WL 20, which JWST revealed to be a pair of stars