For many years I served on the International Astronomical Union (IAU) commission dealing with nomenclature.

One knotty problem concerned the status of Pluto: was it a proper planet?

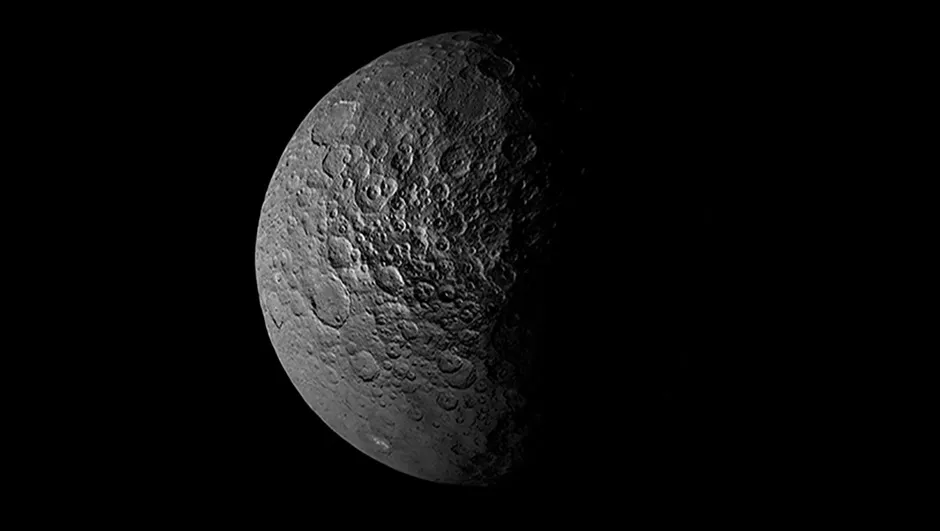

It is smaller than several satellites – our Moon, the Galilean moons in Jupiter’s system and Titan in Saturn’s.

Moreover, it has an orbit which is much more eccentric and inclined than those of the other planets.

It did not even look like a planet. So ought it to be classed as a maverick asteroid?

There was something of a parallel with the discovery of Ceres, on 1 January 1801.

Ceres was promptly hailed as a new planet, despite its smallness.

Doubts arose when Pallas, Juno and Vesta were found between 1802 and 1807; the four became known collectively as asteroids, planetoids or minor planets.

But after 1846, discoveries became fast and furious. The asteroids, even Ceres, were dismissed as nothing more than cosmic debris.

Now, we have the same situation with regard to the Kuiper Belt.

Pluto is the brightest member of the swarm of Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs), but it is not the largest, and others no doubt lurk in those far reaches of the Solar System.

When I had to leave the IAU commission, Pluto had officially clung onto its planetary status, but I think we all knew that there was a certain degree of sentiment about this.

Certainly I felt it, as an old friend of Clyde Tombaugh and junior co-author of his book Out Of The Darkness.

I am afraid that the time for sentiment has passed. If Pluto is a planet, then so are Varuna, Quaoar, Sedna and the rest.

We have to come to a decision; the longer we leave it the more difficult it will be.

Pluto: planet or no?

So let us look at the possibilities. First we have to decide whether Pluto really is exceptional, or whether it is simply a normal, if over-large, KBO.

It has a satellite, Charon, more than half its diameter, and two tiny attendants have been discovered; but other KBOs have satellites.

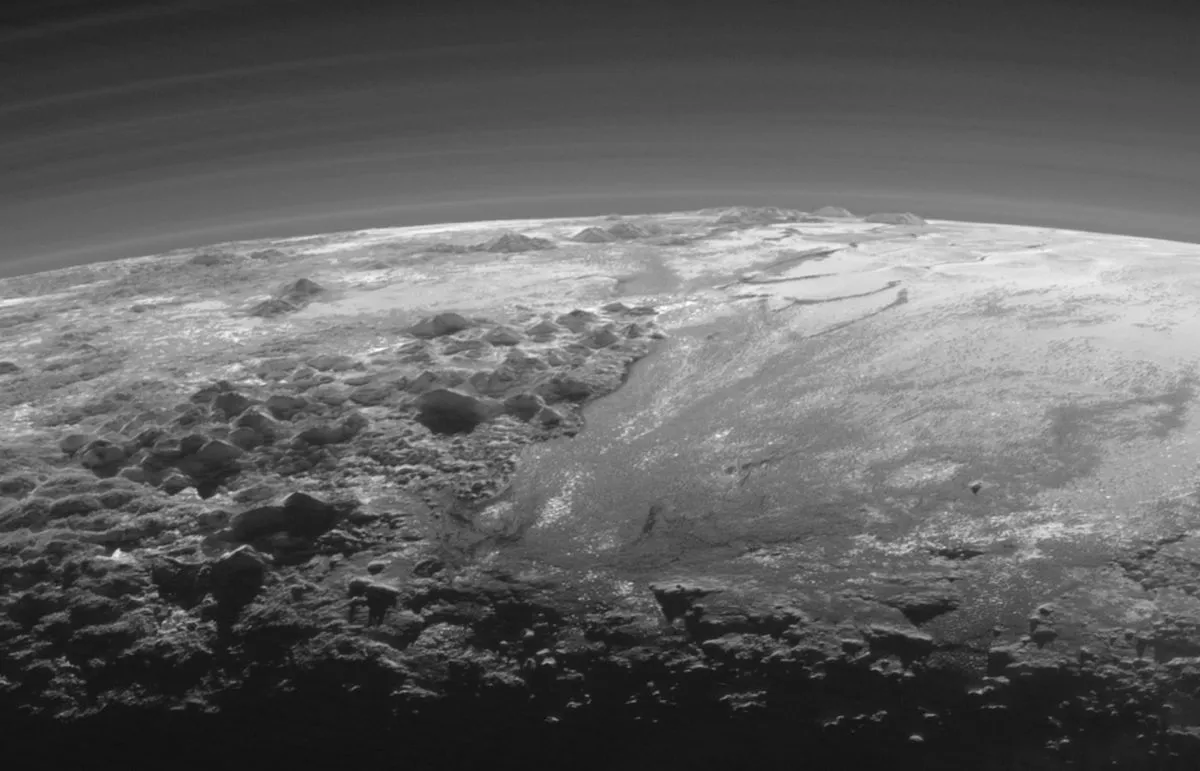

Pluto is the brightest of the KBOs, but not the largest. It has an extensive – if tenuous – atmosphere, but the same may well be true of other KBOs.

There does not seem to be anything really remarkable about its spectrum.

So it really begins to look as though Pluto is merely the senior KBO, just as Ceres is the senior asteroid.

Incidentally, there is another point here. The asteroids (at least those of the main Asteroid Belt) are sandwiched in between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars, and though it is true that Mars is vastly smaller than Jupiter, it is still much larger and more massive than any asteroid.

In fact, all the Main Belt asteroids combined would not add up to Mars. It is conceivable that KBOs are sandwiched in between Neptune and another giant planet much further out.

Before the discovery of the Kuiper Belt I was convinced that Lowell’s Planet X was real.

I am not so sure now, but I am still not a total sceptic.

I was excited when one of the Pioneer spacecraft was not moving quite as expected. Could it be being perturbed by Planet X?

Alas, the other Pioneer, on the opposite side of the Solar System also showed perturbations, and another attractive idea had to be jettisoned.

I cannot believe that there is really a close link between KBOs and comets, even though Chiron at least among bodies of this size does show some cometary characteristics.

Vast though comets may be – sometimes larger than the Sun – they are flimsy by any standards; I once described a comet as being “the nearest approach to nothing that can still be anything”.

I quite agree that some near-Earth asteroids may be ex-comets that have lost all their volatiles, but Chiron is far too large.

The IAU has still not come up with a definite decision about Pluto, but in my mind at least, neither Pluto nor any other KBO can be ranked with the accepted planets of the Solar System.

(About planets of other stars we have no positive information, so that any discussion of status is premature.)

Here is my suggestion, which I make with the full knowledge that others will disagree.

In this classification, a planet must:

- orbit the Sun

- have a well-defined surface – either solid, or gaseous as with Jupiter; and

- be over 3,000 miles (4,828km) in diameter

Why 3,000 miles? Well, Mercury, the smallest of our unquestioned planets, is 3,030 miles (4,880km) across, so that in this system it qualifies, while Pluto does not.

If Planet X eventually turns up, and is found to have a diameter of, say, 2,900 miles, there will be more discussions.

Also, a name will have to be found for it, and here again we come back to Pluto.

Originally, all planetary and asteroidal names were mythological, but so many asteroids were found after 1846 that the supply of gods and goddesses ran out, and some asteroid names are truly bizarre – Cheshirecat and Mr Spock, for example.

Nowadays the discoverer of an asteroid is entitled to recommend a name, and this is rubber-stamped by the IAU commission.

In my experience at least, there is no instance of a discoverer’s choice being turned down, though there are definite guidelines.

Mercifully, politicians and military leaders are banned, so that there is no danger of finding Iain Duncan Smith orbiting close to Harold Wilson.

When a new planet was discovered by William Herschel in 1781, it was often referred to simply as ‘Herschel’, and only later became ‘Uranus’ after the original ruler of Olympus.

In 1846 French astronomers wanted to name the next planet ‘Le Verrier’, but ‘Neptune’ prevailed.

In 1930, the name ‘Tombaugh’ was never put forward, and ‘Pluto’ – after the God of the Underworld – seemed to be eminently suitable.

Another choice was ‘Minerva’. However, this was the suggestion of TJJ See, and to say that See was unpopular with his contemporaries is to put it mildly.

That is why Minerva is called Pluto.

This article originally appeared in the February 2006 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.