Every astronomer dreams of discovering something new – a comet or asteroid, or perhaps a supernova.But in 1915 the Scottish-born astronomer Robert Innes of the Union Observatory, Johannesburg, made a truly historic find: the nearest star to the Sun.

Known as Proxima Centauri, this faint dwarf star in the southern constellation of Centaurus has none of the trappings of a celestial celebrity.

Despite being just 4.2 lightyears from the Earth, its average visual magnitude is barely 11, making it so dim that it can only be seen in sizeable telescopes.

By comparison, if the Sun were at the same distance away as Proxima Centauri it would appear as bright as the Pole Star.

Read more:

- What are the biggest objects in the Universe?

- What are the weirdest stars in the Universe?

- What is a neutron star?

How far away is Proxima Centauri?

Early measurements showed that Proxima Centauri was about it at around 4.32 lightyears, but by the 1970s it had crept down to 4.28 lightyears.

Hopes of a definitive value were raised in 1989 with the launch of the European Space Agency’s Hipparcos satellite, which set about measuring the positions and distances of 120,000 stars with unprecedented precision.

Its value for Proxima’s distance was certainly impressively precise: 4.223 lightyears give or take around 0.013 lightyears.

But in 1999, a team led by Fritz Benedict of the University of Texas used the Hubble Space Telescope to pin down the distance of Proxima even more precisely: 4.243 lightyears (give or take 0.002 lightyears).

This is not only higher than the Hipparcos result – it also lies outside its most plausible range of values. And it’s still not clear which one is closer to the truth.

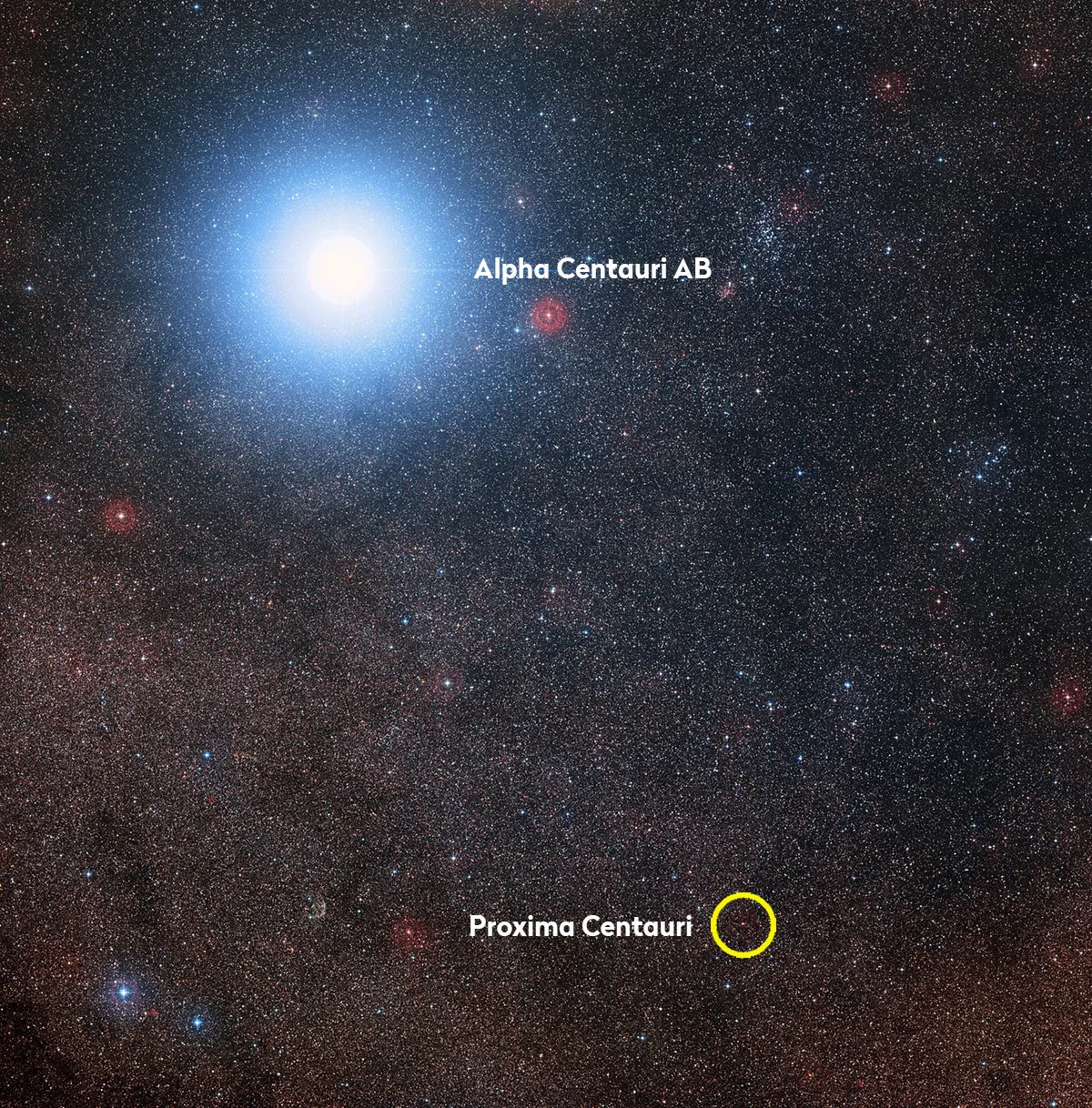

This might seem like a petty academic quibble. After all, both values confirm Proxima’s status as the closest star to the Sun, and put 1,000 billion km of space between it and its nearest rival, the binary star system Alpha Centauri A/B.

But pinning down its exact distance has a direct bearing on one of the biggest puzzles surrounding Proxima: is it actually part of the Alpha Centauri A/B system?

Astronomers have long harboured doubts about Proxima’s status as a free-roving star. By monitoring its position over time, they have been able to work out not only its distance, but also its motion through space.

By as early as 1917 it was clear that Proxima is not only close to Alpha Centauri A/B, but is also moving at a similar rate through space.

More recent measurements have confirmed this odd coincidence and calculations suggest the chances of getting such similarities by fluke alone are less than one in a million.

Not surprisingly, this has prompted many astronomers to decide that Proxima is not a separate star at all, but part of the Alpha Centauri system.

To this day, many textbooks refer to Proxima as ‘Alpha Centauri C’.

In 1993, Professor Gerard Gilmore of the University of Cambridge and I showed that Proxima could be travelling through space fast enough to escape the clutches of Alpha.

Frustratingly, however, the measurements of the motion of Proxima and Alpha weren’t quite precise enough to be sure.

Since then, the mystery of Proxima’s motion has taken a new twist. Studies of planet formation suggest the Alpha Centauri A/B system could harbour exoplanets.

According to research by Dr Jeremy Wertheimer and Dr Gregory Laughlin of the Lick Observatory, California, the presence of Proxima could help stir up the gas and dust in the system, helping to form Earth-like worlds.

Questions about Proxima’s relationship to Alpha Centauri A/B have implications for the existence of habitable planets on our doorstep.

Using the latest data on the motion of Proxima, Wertheimer and Laughlin conclude that Proxima probably is caught in the gravitational field of Alpha.

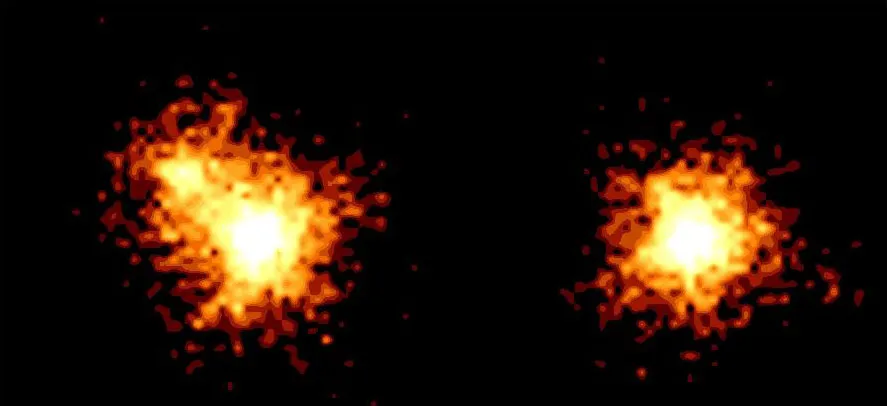

Studies by the world’s largest telescope, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, are providing an ever more detailed portrait of our celestial neighbour.

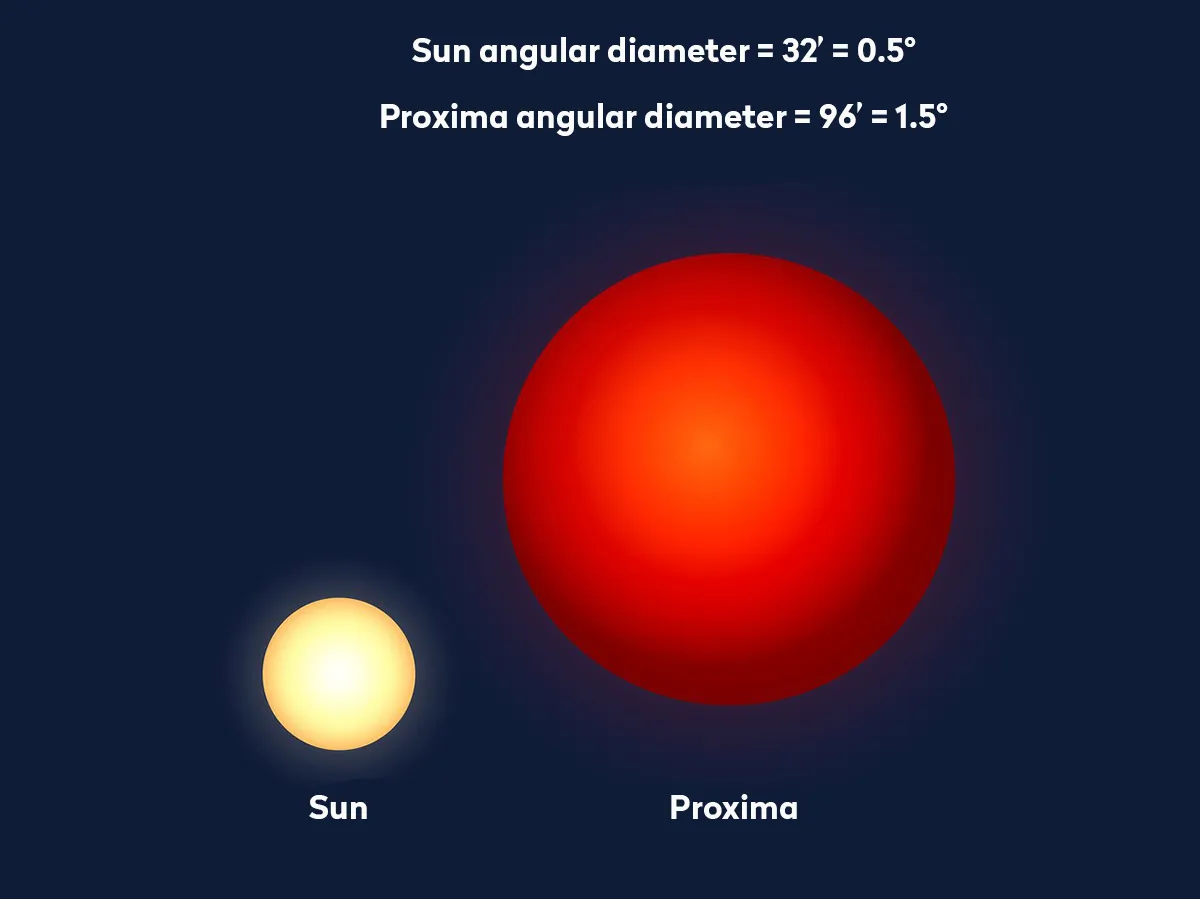

By combining the light of two of the VLT’s giant 8m (26ft) telescopes separated by over 100m (328ft), a team at ESO has succeeded in measuring the actual size of Proxima.

Even using these titanic telescopes, Proxima’s disc was hard to detect, being equivalent in size to a hair’s breadth seen from a distance of 20km (12 miles).

In real terms, that makes Proxima barely 50% larger than the planet Jupiter.

Combined with its mass of just one-seventh that of the Sun, Proxima is teetering on the brink of not being a star at all, lacking the bulk to ignite the fusion reactions that produce starlight.

Already around 6 billion years old, quite how long this dim flare star can continue to flicker in the celestial gloom is unclear.