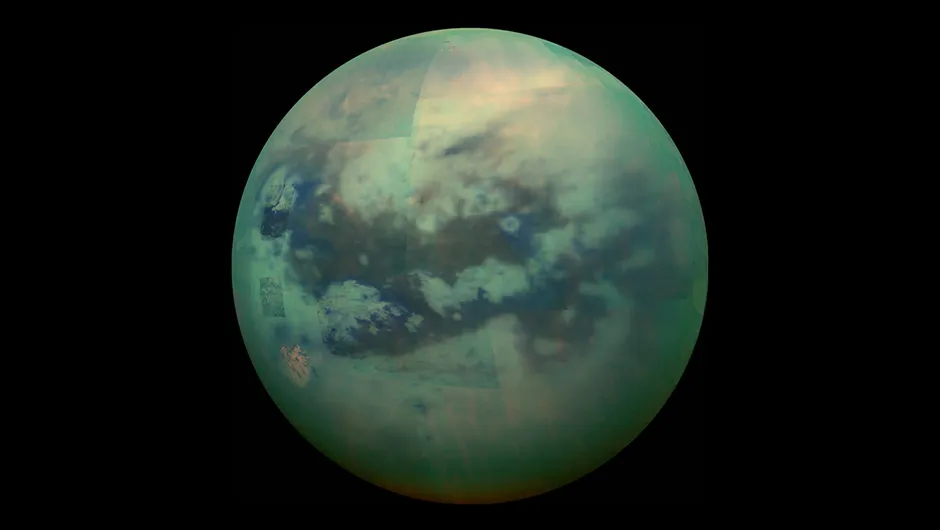

One of the most stunning discoveries delivered by NASA’s Cassini probe to the Saturn system was that its moon Titan hosts a number of lakes (confirming evidence from the Hubble Space Telescope).

Titan is a giant moon with a thick atmosphere, and had long been suspected to offer appropriate conditions for bodies of liquid methane and ethane on its surface.

The largest of Titan's lakes, Cassini found, range from hundreds of kilometres to over 1,100km in length, and so are referred to as seas.

The probe also spotted hundreds of other smaller lakes, ranging from just a few kilometres to 240km.

Some of these bodies exhibit intricate shorelines, and many cluster together near the north pole: a Titanic Lake District.

Seas and large lakes on Earth affect the local wind conditions.

They take longer than the land to warm up and cool down on a day-to-night cycle, as well as over the seasons, and evaporation from their surface also affects heat transfer.

The temperature differentials created by these factors generate either onshore or offshore winds.

So a natural question arises: how do Titan’s large methane lakes affect the moon’s winds?

Previous studies have explored this with 2D models, but Audrey Chatain at the Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, and her colleagues, improved on these efforts by simulating atmospheric movements around Titan’s lakes in all three dimensions.

Chatain’s models show that although the conditions on Titan and Earth are extremely different, the breezes formed around Titan’s lakes are actually broadly similar to those on Earth in terms of the extent of the winds above the surface and how far inland they penetrate.

Her team also found that these surface winds are strongest around the edges of the largest seas, and for lakes nearer the equator during summer, as would have been expected.

But even in these situations, Chatain calculates that these lake winds never exceed a very gentle breeze

of 0.2m/s – far slower than analogous lake winds on Earth of around 5m/s.

She notes that even these strongest lake breezes on Titan would not be enough to create wind-driven waves on the moon’s seas.

Chatain’s team also determined an evaporation rate from Titan’s lakes of around 6cm per Earth year,

which is far lower than the values of 20–50cm suggested by previous, simpler 2D models.

Another new result from these 3D models is the formation of a stable layer of cold but moist air in the first few metres above the lakes.

Chatain calculates that under these conditions the evaporating methane could reach saturation and condensation: Titanic sea fogs.

Overall, the winds on Titan are much weaker than those on Earth, so although far-future explorers may experience the singular pleasure of a boat ride on liquid hydrocarbon seas, they’d struggle to go sailing.

Lewis Dartnellwas reading The Impact of Lake Shape and Size on Lake Breezes and Air–Lake Exchanges on Titan by Audrey Chatain et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2309.07042

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine