Over the past few months, astronomers have been keeping an eye on Saturn’s rings as they slowly disappear.

On 23 March 2025, Saturn's rings will vanish from view.

Don’t worry, their disappearance is only temporary as they’ll be returning just a few months later.

When Saturn’s rings vanish like this, astronomers call the event a ring plane crossing and it’s all down to how we view Saturn from Earth.

Saturn's orbit and ring tilt

Lying at an average distance of 1.43 billion kilometres (886 million miles) from the Sun, Saturn takes 29.4 Earth years to complete one orbit of our star.

As it orbits the Sun, Saturn experiences seasons and solstices due to its axis of rotation being tilted by 26.7°.

Earth is also tilted in its orbit, by 23.5°, and as both planets travel around the Sun in their own orbits, the way we see Saturn’s rings from Earth slowly changes.

Sometimes we see Saturn's rings from above and sometimes from below, the Sun illuminating them.

But when the Sun shines directly over Saturn’s equator during the Saturnian equinox, we see the planet and its rings edge-on, creating the illusion of the rings ‘disappearing’.

Why ring plane crossings are a big deal

Ring plane crossing events are fairly rare, occurring around every 15 years.

While the bright, highly reflective rings are temporarily out of the way, they provide a great opportunity for astronomers to make new discoveries.

According to NASA, between 1655 and 1980, 13 moons of Saturn were discovered during ring plane crossings.

Astronomers also grab the chance to study the orbital motion of the planet’s moons and observe transits, occultations and even eclipses.

About Saturn's rings

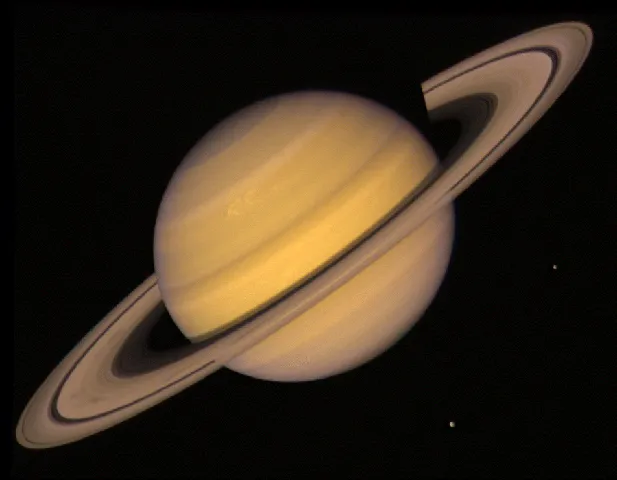

Saturn is one of the most distinctive planets in the Solar System.

Composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, it is the second-largest planet, with a whopping diameter of 116,500km (72,400 miles).

Its beautiful ring system makes the planet unique and was first observed by astronomer Galileo in 1610, when he reported what through his early telescope looked like ears or handles on the planet.

It wasn’t until almost 50 years later that Christiaan Huygens discovered that the ‘projections’ Galileo had seen on Saturn were in fact a ring.

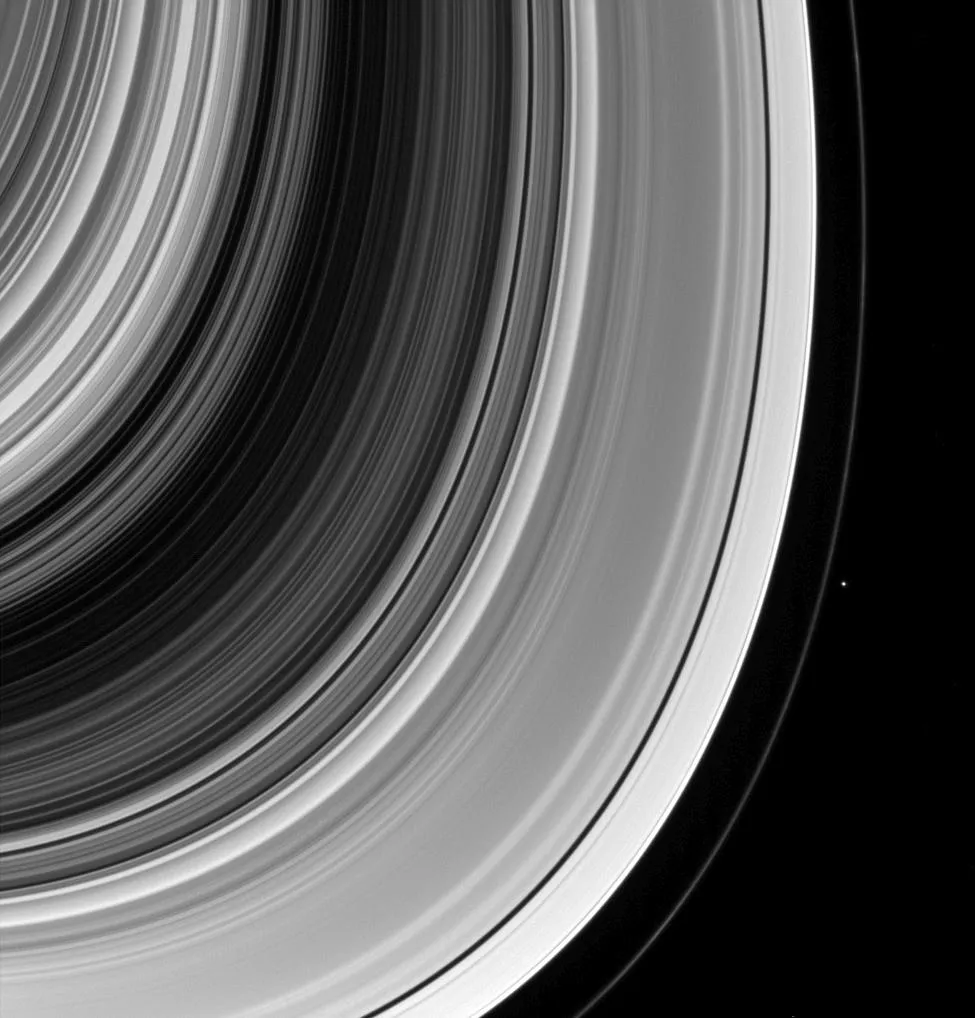

Twenty years later, Giovanni Cassini identified more than one ring and spotted gaps between them.

The two brightest rings that he could see are named A and B, and the huge 4,800km (3,000-mile) gap separating them is named the Cassini Division in honour of his discoveries.

Today, we know that there are seven main rings, A to G, each ‘new’ ring being designated with a letter as it was discovered.

The G ring, located between the E and F rings, is the most recent ring discovery. It was found in 1980 by Voyager 1 as the spacecraft flew by.

Saturn’s rings are complex, separated by sub-divisions, gaps and ringlets.

They are spread over 282,000km (175,200 miles) and almost entirely composed of particles of water ice ranging in size from tiny grains to boulders tens of metres in diameter.

The rings are surprisingly thin – only around 1km (0.6 miles) in thickness.

Where Saturn's rings come from

The series of thin rings that make up Saturn's ring system once contained high-energy particles that were highly inclined in their orbits, which collided with other particles.

As these collisions slowed down or stopped, the particles would move to lower-energy orbits and over time flattened into thin, flat discs surrounding the planet.

A recent study has suggested that Saturn’s rings are not as ancient as astronomers once originally thought, but instead may be no more than 400 million years old.

Will we see Saturn's rings disappear?

Unfortunately, Saturn isn’t well placed during the March 2025 ring plane crossing and will be too close to the Sun for us to observe the complete disappearance either from Earth or with telescopes in space.

It doesn’t emerge from the Sun’s glare again until late April, in the early morning twilight.

The planet will be further from the Sun in its orbit and much better placed for the whole of the next ring plane crossing, but that’s not until 2038.

So it’s just as well that, as astronomers predict, Saturn won’t lose its rings forever for another 300 million years!

Have you been observing Saturn's rings, tracking their tilt? Share your experiences, sketches and images by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com