Space is booming. Satellites monitor the climate, connect us to the internet and help us to study the Universe.

Someday soon we could get back to the Moon.

Spaceflight is getting cheaper as new commercial companies build rockets and spacecraft, while dangling the promise of space tourism.

This is all very exciting, but at the same time, both scientists and industry workers are nervous about the potential dangers of uncontrolled proliferation.

Streaks are increasingly spoiling astronomy images, while the threat of space advertising is rearing its head.

The population of orbital debris - known as space junk - could grow to pose unacceptable risks to spacecraft and leave space companies squabbling over real estate.

The UK space industry’s satellite-building capabilities – which cover all space applications from telecommunications to Earth observations to exploring the depths of the Universe – are internationally renowned and contribute huge amounts to the British economy every year.

They are just as keen as any astronomer to make sure key orbits remain usable. Is there a way we can reach a sensible and fair compromise?

The wonder of astronomy

I’ve always been a space geek. I was a wee boy when Yuri Gagarin launched into orbit and I’ve been hooked ever since.

Soon I was obsessed with stars and galaxies and quasars.

As I emerged from my education into a PhD in X-ray astronomy, it was wonderful to see how my love for science and my love for space meshed together.

Over the years, new and more wonderful astronomy space missions appeared – IRAS, the Hubble Space Telescope, XMM-Newton, Gaia – culminating in the astonishing James Webb Space Telescope, partly built where I now work, the Royal Observatory Edinburgh.

I’ve also used many ground-based telescopes and have specialised in working on big sky-survey projects.

Right now, I am looking forward to the Vera Rubin Observatory, a huge telescope currently under construction in Chile that will scan the entire overhead sky every few days.

Here in Edinburgh we’re working with Belfast and Oxford to build a system to trawl through these images, looking for supernovae, flaring quasars and potential ‘killer rocks’.

Satellites spoiling the view

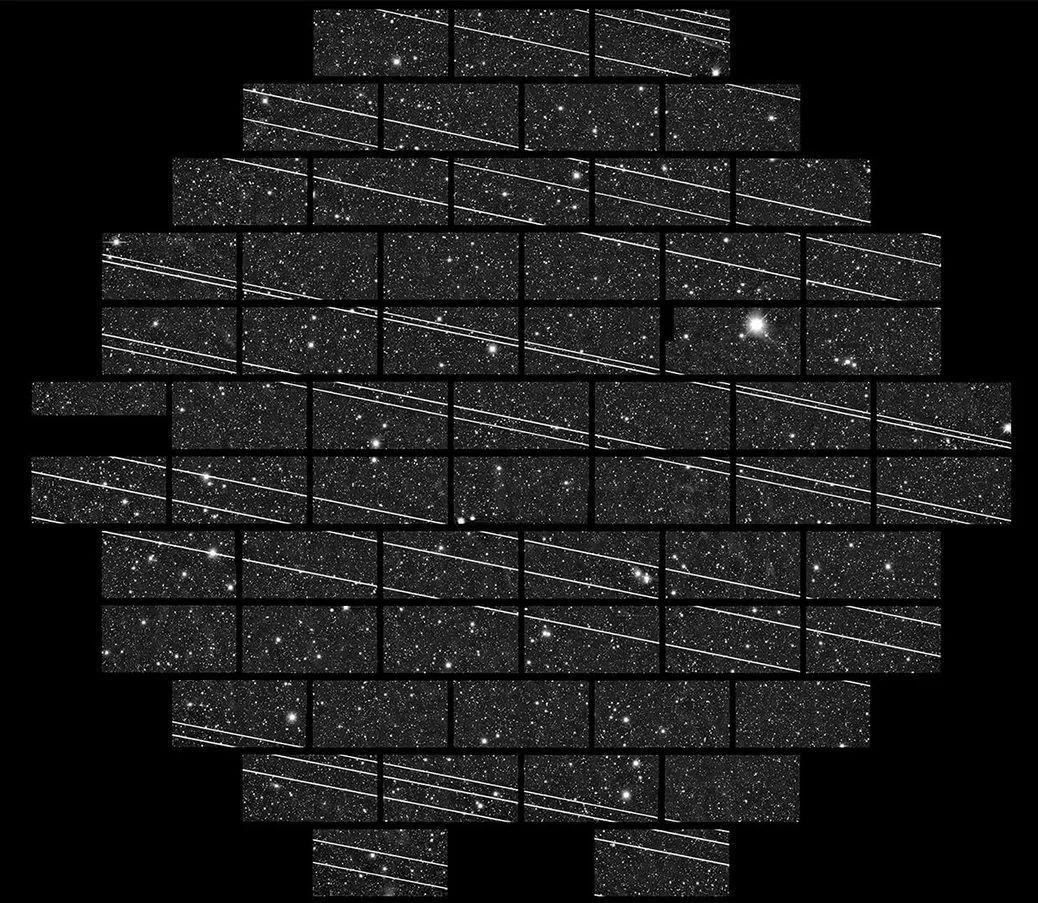

In late 2019, the warm glow I got from the synergy of astronomy and space was suddenly cooled by a splash of cold water – an image from the Dark Energy Survey, similar to those we hope for soon from Rubin, was painted with bright streaks from Starlink satellites passing by.

Soon, people all over the astronomical community were reporting other issues, including huge streaks in Hubble images.

Over the last few years, the number of active satellites has more than doubled. By the end of the decade there could be tens or hundreds of thousands, outnumbering stars in the sky.

A series of workshops led by US astronomers studied the problem and eventually led to the creation of the Center for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky, endorsed by the International Astronomical Union.

In the last few years, I’ve concentrated on public awareness, writing a book called Losing the Sky, but also getting tangled up in legal and regulatory cases.

I’ve become aware of the broader issues – space junk, commercial fairness, liability, space advertising – and see the issue as one of space environmentalism.

The sky is perhaps the last pristine wilderness.

We know that it is unrealistic to preserve it as completely untouched, and we positively want the benefits that can come from commercial space activity.

But how do we balance the benefits against the damage and make space a happy playground for everybody?

These are questions we’re still looking for answers to.

This article originally appeared in the July issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.