Nearly five million years ago, when mammoths were just starting to roam Earth, a star called S5-HVS1 had a bad day. It had living as one half of a binary system that had yet to stray far from the neighbourhood in which it had formed.

S5-HVS1 and its as yet unidentified companion formed in the gas clouds in the middle of the Milky Way Galaxy.

As a normal A-type star, it was destined for a brief blaze of glory, a lifetime of a billion years or so shining as a bright blue-white component of its natal cluster.

Also by Prof Chris Lintott:

- Do spiral protoplanetary discs mean exoplanets in orbit?

- Chris Lintott talks citizen science

- Four objects examined in Planet 9 search

The binary passed close by the supermassive black hole that sits right at the centre of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

The gravitational dynamics are complicated, but when three bodies – in this case two stars and a black hole – interact, one can be expelled at high speed.

The massive star shot through the Galaxy for millions of years, before being noticed by astronomers at the Anglo-Australian Telescope in Siding Spring, Australia.Researchers measured the star’s speed at 1,755 km/s (over 6 million km/h).

It’s hard to work out how a star could reach such a speed without tangling with the Milky Way’s central black hole, and when they traced back its path, it does seem to have come from that direction.

Its path traces back to the ring of bright young stars we observe around the black hole today, raising the possibility that its erstwhile companion might still be sitting there waiting to be discovered.

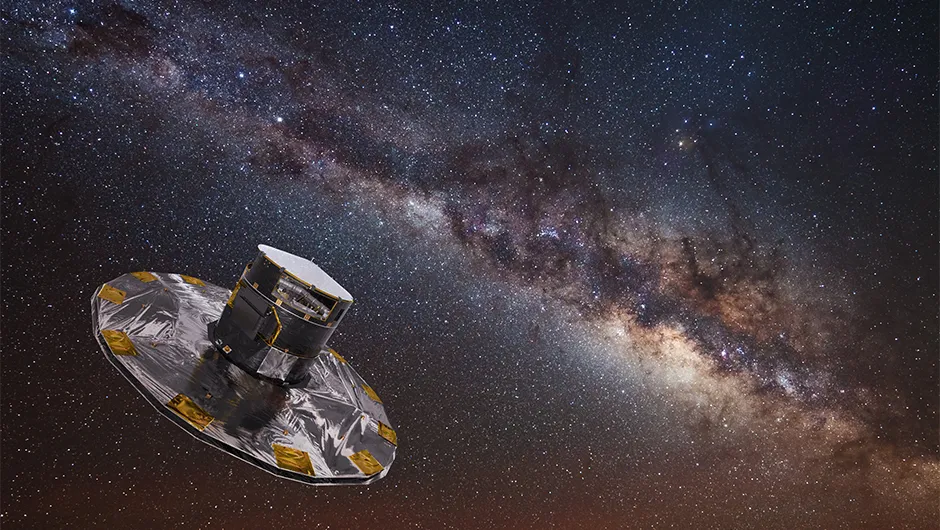

With new results from ESA's Gaia mission expected in a year or two, and new spectroscopic surveys of the sky planned, the star won’t expect to keep its special status for too long; there should be dozens of similar stars within our grasp.

Find enough of them and we might be able to begin to work out the recent history of our neighbouring supermassive black hole.

Flurries of stars might indicate episodes where the material around the central black hole has been disrupted, or when it was especially active.

It’s also possible the movements of other hypervelocity stars might help us trace the distribution of the mysterious dark matter that makes up most of the Milky Way’s mass.

Though it’s alone, we can learn a lot from this single star.

The fact that it exists says that a supermassive black hole can accelerate stars, a process first proposed 20 years ago but never before unambiguously observed.

We can also use it to refine our understanding of the position of the Sun. If we assume it comes from the Galactic centre, then we can get a better measure of how far away we are.

Because of this single star shooting past us, we now know we lie precisely 26,484 lightyears from the centre of our Galaxy.

Not a bad legacy for a star that’s just passing by.

Did you know that the Milky Way is expected to collide and merge with the Andromeda Galaxy in the very distant future? Read more in Chris Lintott's guide to the Andromeda-Milky Way collision.

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

Prof Lintott was reading The Great Escape: Discovery of a Nearby 1700km/s star Ejected from the Milky Way by Sgr A* by Sergey E Koposov et al. Read it online here.