The study of exoplanets is one of the hottest topics in astronomy today. There's something entirely enthralling and mesmerising about our ability to peer beyond our Solar System and observe a plethora of planets orbiting distant stars.

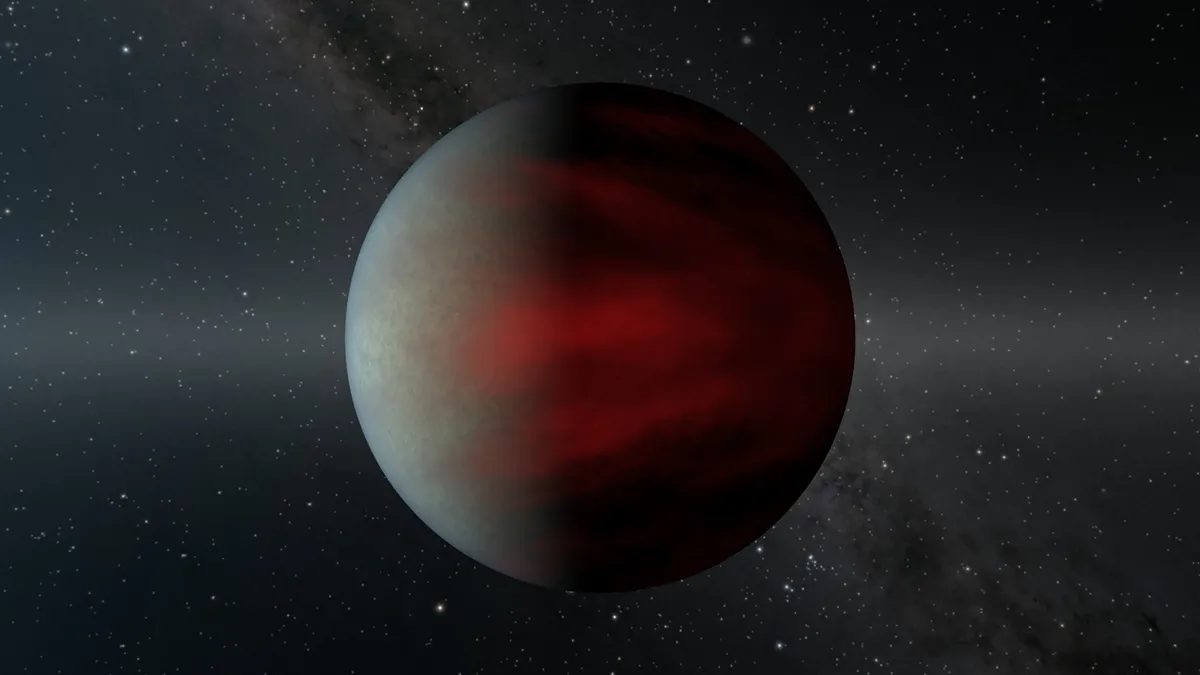

Exoplanet astronomers have discovered scorching hot gas giants called 'hot Jupiters' and so-called super Earths, revealing there is much to learn about the kind of planets that exist elsewhere in the Galaxy and, in many cases, why we don't see similar worlds in our own Solar System.

Read more:

- How the Hubble Space Telescope is used to study exoplanets

- A guide to the latest exoplanet-hunting missions

- Is it possible to map an exoplanet?

Niall Deacon is an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy who studies brown dwarfs. These extra-solar objects have too little mass to become a fully fledged star, but also too much mass to be classed as a planet.

To mark the release of Deacon's new book Twenty Worlds, we got the chance to speak to him about exoplanet science, and some of the incredible discoveries that have been made over the past two decades.

Why is exoplanet study such a hot topic in astronomy?

Exoplanet science is a relatively new field of study. A hundred years ago the study of galaxies outside the Milky Way got going in earnest and suddenly there was a whole Universe to explore.

October 2020 marks the 25th anniversary of the first exoplanet being found around a star similar to the Sun.

Astronomers keep improving techniques, learning more about a range of planets, from gas giants to small worlds similar to Earth

This opened a whole cornucopia of weird and wonderful worlds for our imaginations to run riot in: real, physical planets that our brains link to the fictional locations in sci-fi.

It’s also a whole new field of science to explore with new planets to discover and new physical processes to learn about.

What are the strangest exoplanets we know of?

The most mind-blowing for me are three planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B 1257+12.

These are likely the result of a neutron star ripping its white dwarf companion to shreds with the planets forming from the debris of the white dwarf.

As the white dwarf was made mostly of carbon these planets probably have cores of crystallised carbon (aka diamond).

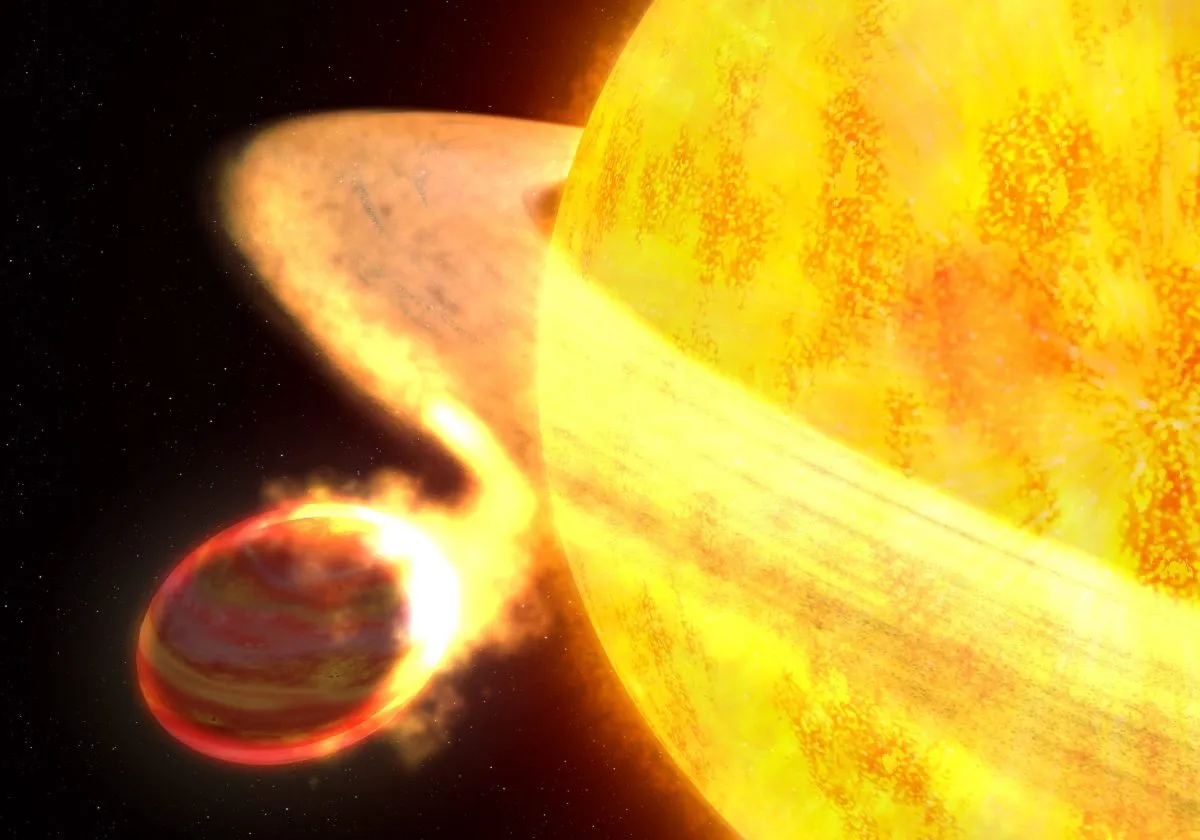

Then there’s WASP-12b, a gas giant that is so close to parent star that the intense stellar radiation has caused it to swell up so much that it’s falling apart.

Finally, I’m still amazed that asteroid dust has been detected in the atmospheres of white dwarfs and that the first evidence for this was found in 1917, but wasn’t correctly interpreted for 90 years.

What can exoplanets teach us about our Solar System?

The Solar System is a snapshot in time: 8 middle-aged worlds around one star of one particular type.

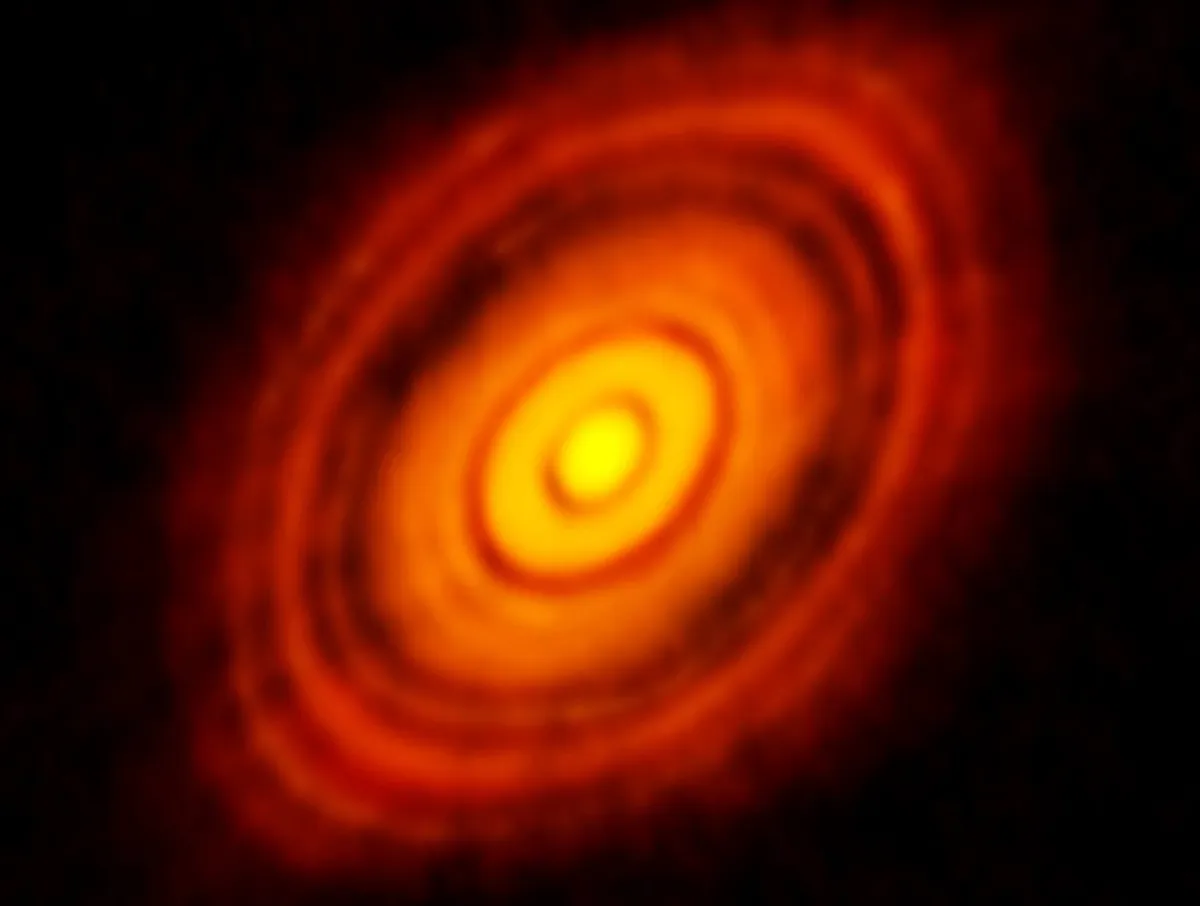

By studying exoplanets we have access to a time machine and can look at the still-forming worlds in huge discs of gas and dust around young stars. This teaches us about out how our Solar System formed.

Also, we can look for signs of planetary systems around stellar remnants like white dwarfs to see the far future of our Solar System.

So many discoveries in exoplanet science...have been things we had never expected to find and had never even been looking for.

Finally, we can look at the statistics of a wide range of exoplanet systems, how many planets there are of certain types in certain orbits around certain stars.

This teaches us about physical processes that could have affected the planets and worlds in the Solar System.

We can see how exoplanets have migrated from the orbits they formed in and how their atmospheres have been sculpted by heat, light and huge winds of high-energy particles from their parent stars.

Could we send a robotic probe to visit an exoplanet?

There’s been a proposal to send a swarm of probes to Proxima Centauri b, the planet orbiting the nearest star to the Sun, Proxima Centauri. This would need a huge amount of money and technological progress.

Also, it would take at least a generation for the probe to get there and there would be no guarantee of success.

I think exoplanet science would benefit more from putting all that time, money and effort into other projects based on more conventional observing techniques but with better, larger telescopes.

What are your hopes for the future of exoplanet study?

I think there are two answers to this question. The first is that astronomers keep improving their current techniques, learning more about a whole range of planets from gas giants to small worlds similar to Earth.

We might even be able to do detailed studies of the atmospheres of rocky worlds with the correct surface temperature for liquid water.

I hope for lots of fantastic discoveries that no one has predicted and that we can’t imagine right now.

The other answer is that the Universe always finds new ways to surprise us.

So many discoveries both in exoplanet science and astronomy in general have been things we had never expected to find and in many cases had never even been looking for.

We didn’t expect to find gas giants orbiting close to their parent stars or to find planets orbiting pulsars.

Hence, I hope for lots of fantastic discoveries that no one has predicted and that we can’t imagine right now.

Twenty Worlds by Niall Deacon is out now via Reaktion Books.

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's staff writer. This interview appeared in a shortened form in the October 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.