Cast your mind back to 1962. We thought we knew a great deal about the structure and origin of the Universe.

Well, we certainly knew something, but many of the ideas that were current at that time have since been cast aside.

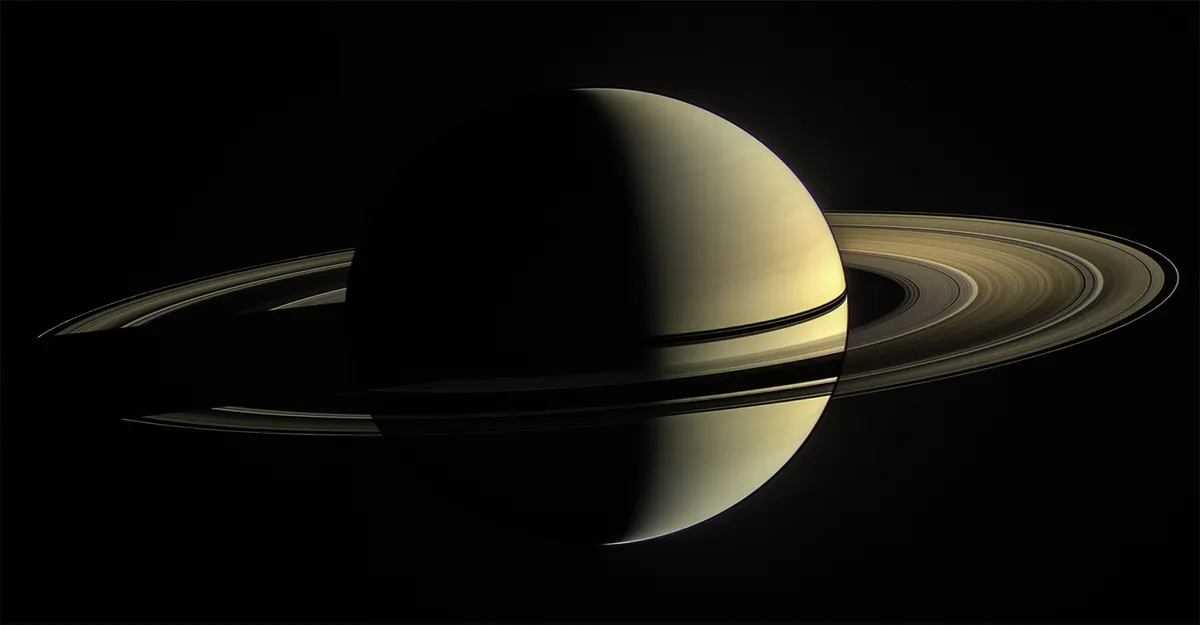

First, consider the age of the Universe. It was known that the Universe was very old, but estimates ranged from below 10 billion years to over 20 billion years.

Secondly, how did it begin – and how will it end?

Here, we were on slightly firmer ground. At least we were sure that the stars and galaxies formed by condensation from a vast cloud of tenuous material.

Thirdly, how did stars generate their energy? Einstein’s theory of relativity had become generally accepted by 1962, though there were some astronomers who doubted it – and there still are.

At least we know now that the age of the Universe is 13.8 billion years and we are confident that this time we are not far wrong.

But how will the Universe end? Here we have not made a great deal of progress and it is by no means certain that there will be an end at all.

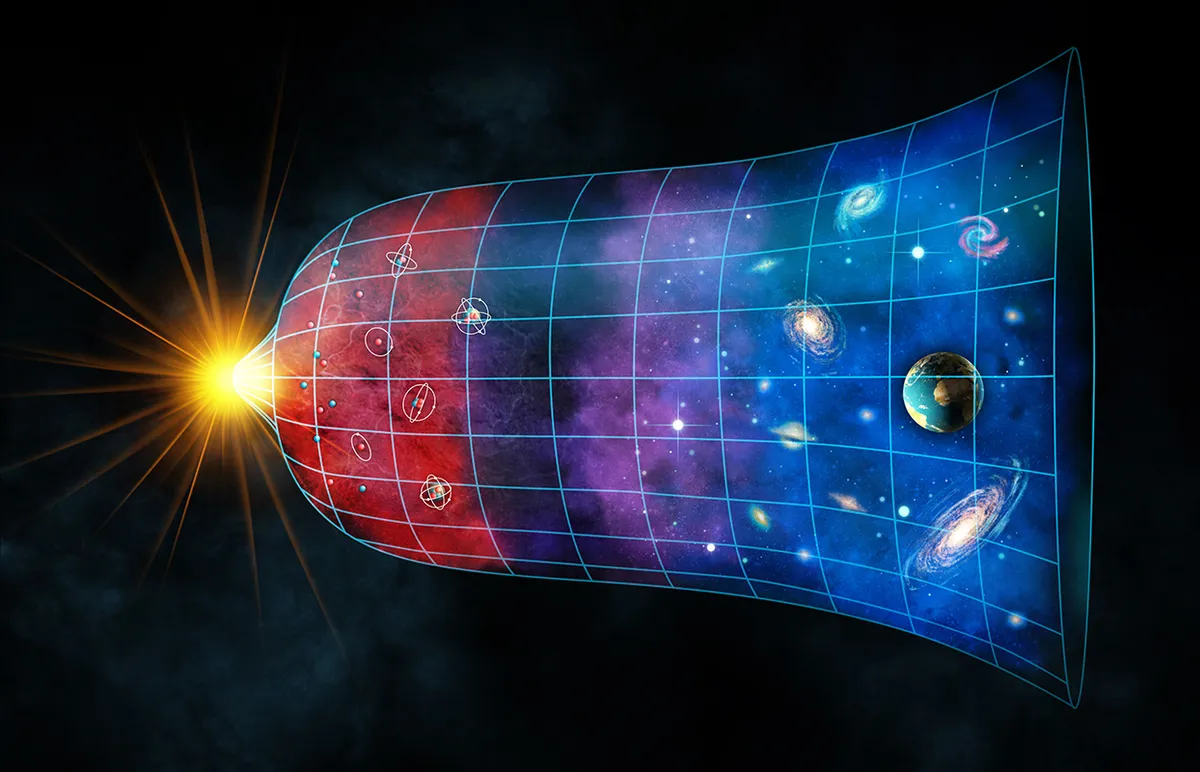

The expansion of the Universe was accepted by most astronomers in 1962 but there were still some doubters. Certainly the idea of a static Universe had been generally discarded.

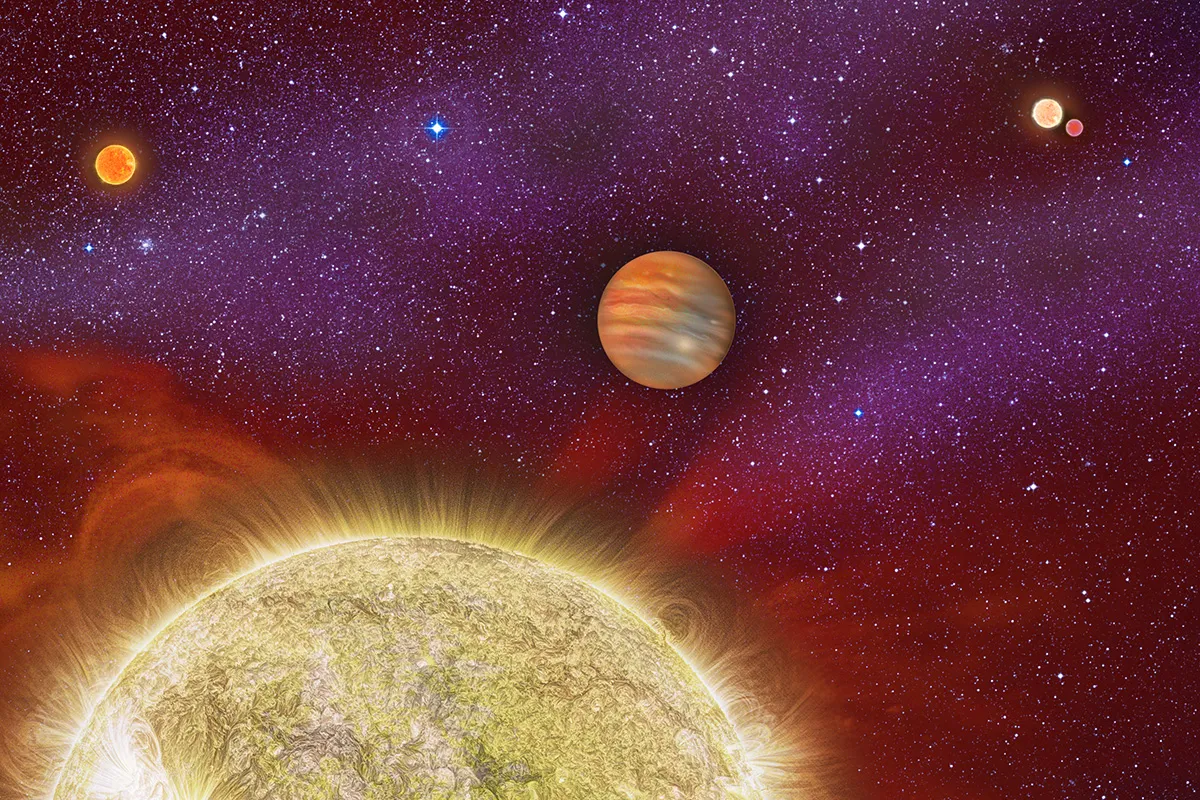

When we come to the source of stellar energy, there have certainly been major changes in our outlook.

All kinds of theories had been put forward, such as the collision of atoms with each other to heat the material, but of course we now know that this is completely wrong.

The stars generate their energy by nuclear reactions. Hydrogen is the essential key, and is also the most plentiful substance in the entire Universe.

Four atoms of hydrogen can combine to make one atom of helium, admittedly by a rather roundabout route.

Every time one helium atom is formed, a little mass is lost and a little energy is released.

It is this energy that makes the stars shine; the loss of mass amounts to a staggering four million tonnes per second.

Luckily for us, there is as yet no prospect of all the available hydrogen being used up.

With regard to the expansion of the Universe, this was generally accepted 50 years ago. It now seems that in its outer regions the rate of expansion is actually increasing, and this leads us on to the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy.

Here we have to admit we are still very much in the dark.

I think most people accept the idea of dark matter, which we cannot see but which betrays its presence by its gravitational effect on the objects we can see.

We have no idea what dark matter is but the evidence in favour of its existence is very strong.

Dark energy is a different proposition altogether – it is assumed to be responsible for the acceleration of expansion of remote parts of the Universe, but what it actually is remains a total mystery.

To my mind, at least, solving the question of the nature of dark matter and dark energy will take us a long way to an understanding of the Universe as a whole.

If present-day theories are correct, dark matter makes up most of the material in the Universe.

What we can see is a very small part of the whole.

This is where we come up against what is so far an impenetrable wall in our knowledge.

We have to break through this before we can make any more real progress.

Then there’s the question of life beyond Earth. Fifty years ago we had to admit we did not have the slightest idea whether or not we are alone in the Universe.

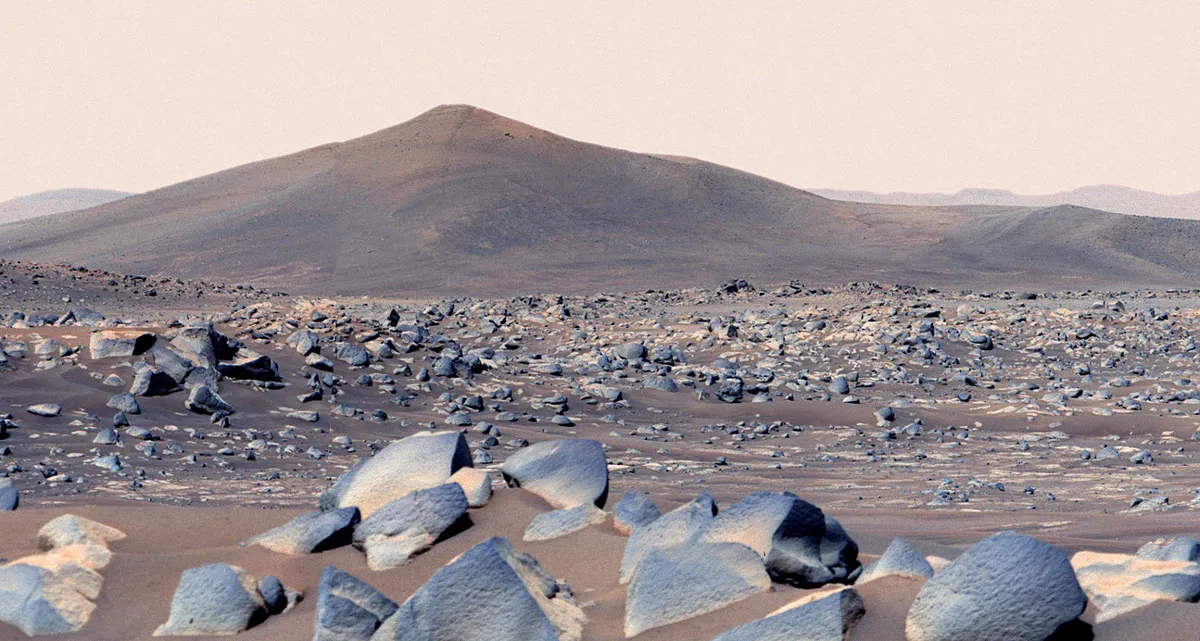

Again, our progress has been very limited, but at least there may be some light and in my view (not shared by many) the key may be Mars.

There are no intelligent Martians, as Percival Lowell once believed, and Lowell’s picture was generally discarded by around 1940. But rockets have given us a chance to make a breakthrough.

With any luck, it won’t be long before we will be able to send a sample-return probe to Mars.

If we manage this our spacecraft will certainly not be met by a welcoming committee, but if it brings back samples that contain elementary life – and if we can prove that this life is genuinely Martian and not Earthly contamination – it would be a pointer to the idea that where life can appear, it will!

We should certainly be able to answer this in the foreseeable future but otherwise we have not advanced a great deal over the past 50 years.

Of course, we have made immense strides in the exploration of very remote parts of the Universe because we have telescopes and spacecraft that would have seemed more like dreams in 1962.

By then we had entered the photographic age and sheer visual observation was going out of fashion.

But now we have come to the age of electronics, which is overtaking photography.

It is fair to say that photography has been more or less abandoned by leading research teams, which has opened up all manner of new fields of research.

Where do we go from here? I am confident that the advances to be made over the next 50 years will exceed those of the past 50, but I cannot go further than that.

When asked what I expect, I simply reply, "I expect the unexpected!"

This may be a cowardly way out but it is the best I can do at the moment. Looking back then to 2012, we may find that some of the ideas that are now current have become hopelessly out of date.

I do not expect to find fundamental flaws in some of our most cherished ideas, but one never knows.

There is very little point in further speculation, but at least we can say that the rate of progress over the last half a century has been more rapid than at any other time in history.

We live in an exciting period and things may well become even more exciting in near future.

As Prime Minister Herbert Asquith said back in 1910, "wait and see!"

My own personal hope would be that we make contact with another intelligent race far across the Universe, which would indeed be fascinating.

Much depends upon the arrival of a new Newton or Einstein.

But if anyone in the year 2062 is able to read this article, they may smile contemptuously, and I would not blame them!

This article originally appeared in the November 2012 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine