Cosmologists have it hard: creating a ‘universe’ is expensive and difficult, and even if you do manage to play God, you have to wait billions of years for the outcome of the experiment.

The cosmologists’ solution is to use powerful computers to create simulations that allow us to see what happens if you try things like changing the amount of mass in a universe.

The trouble is that it’s hard to work out which bits of the Universe you can simulate.

More space science

Creating a realistic view that can be compared with the images and data gathered from today’s telescopes requires keeping track of processes that take place on a large range of scales, from the forces affecting the expansion of the Universe - like dark energy - to the chemistry occurring in star-forming clouds.

It can be done partly through clever programming, but it also requires the use of a supercomputer.

In the case of the CAMELS (Cosmology and Astrophysics with MachinE Learning Simulations) project, there is a massive supercomputer known as ‘Popeye-Simons’ in San Diego.

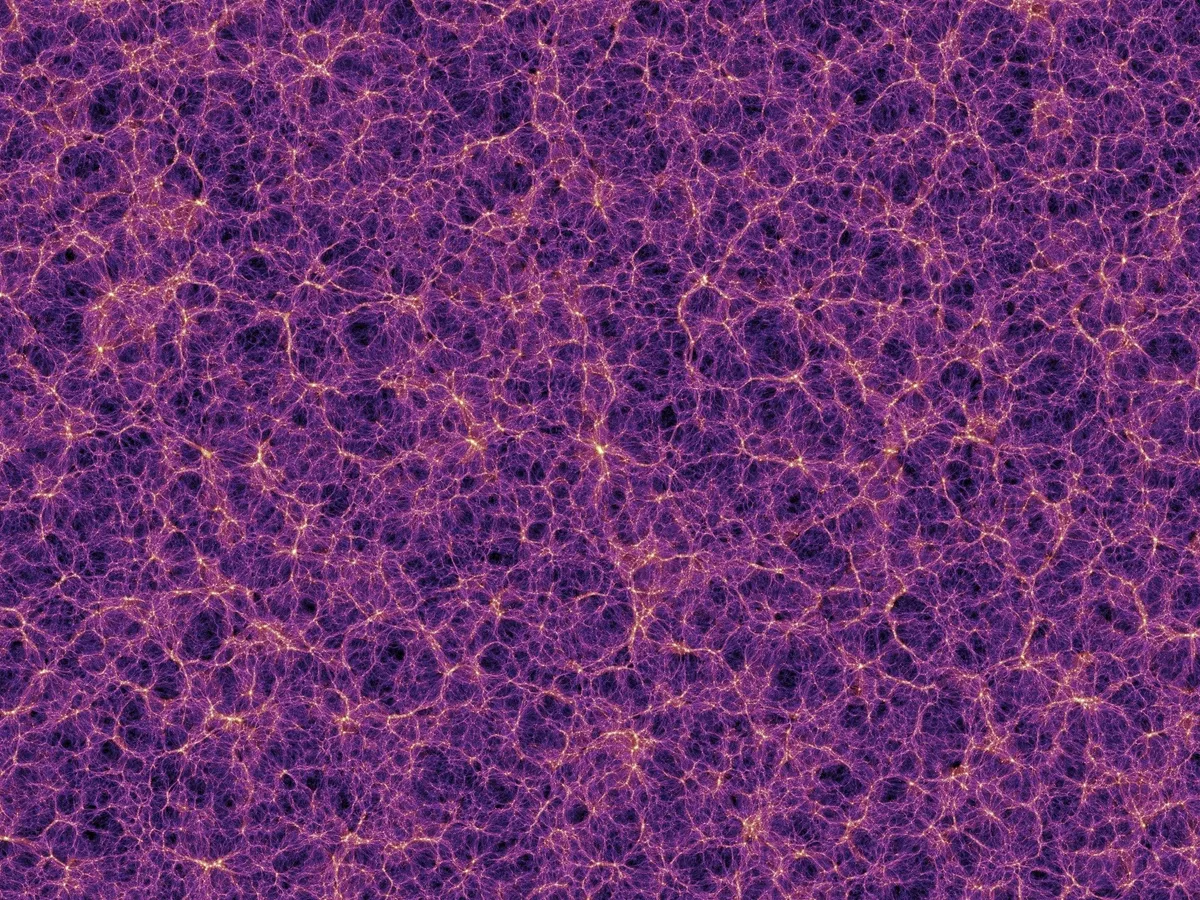

With it the CAMELS researchers have created 4,233 universe simulations.

For some, only the behaviour of the matter moving under gravity is followed – essentially, these are skeleton universes made only of dark matter – but for more than half of the simulations the computer has tried to follow the physics of the gas and stars too.

Each universe is different, as various approaches are used to solve the problem of cramming a universe’s worth of physics into a code that can be run on a computer.

But a crucial set of simulations alters the physics, either changing the density of matter in a universe simulation (how clustered it is) or altering parameters that control how efficiently supernovae and activity associated with a galaxy’s central black hole pump energy into the surroundings.

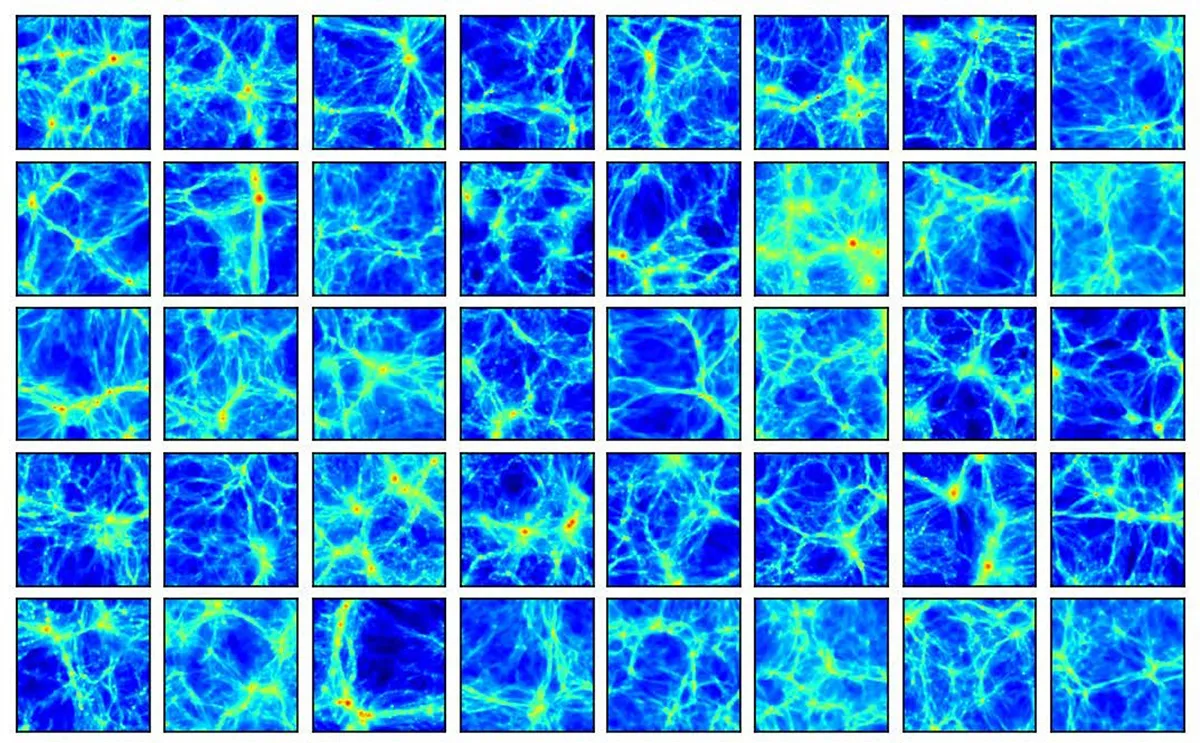

The resulting data and the maps and simulated observations generated from it were made public by the CAMELS team.

Intriguingly, the team also spent a lot of time making its virtual universes accessible to machine-learning algorithms.

These can be used to simulate the work of the simulators, saving time and money by predicting what universes with properties in between those already modelled might be like.

That opens up new angles for investigation.

In the simulations, we know the true mass of a galaxy, so the team used the CAMELS data to train an algorithm that can predict a galaxy’s mass based on its properties.

By turning that on the Milky Way, the team can find a new way to measure the properties of our own, real, Galaxy, from studying millions of artificial equivalents.

The possibility of understanding how much we can say about cosmology, the behaviour of the Universe as a whole, from the study of a single galaxy is exciting.

Simulations used in this way don’t just provide a check on our observations, but suggest new ways we can use our telescopes.

Chris Lintott was reading The CAMELS project: public data release by Francisco Villaescusa-Navarro. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2201.01300.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.