Again and again we're told that according to Einstein's theories of relativity, nothing in the known Universe can expand faster than light.

It violates the laws of physics. It can't be done.

And yet, seemingly contradicting this fundamental law is the idea that the early Universe itself expanded at a rate faster than light.

How can this be? How did the early Universe expand faster than the speed of light, if no matter can travel faster than light? Doesn't this contradict relativity?

Read more:

- What is gravity?

- What would happen if you fell into a black hole?

- What's the difference between Newton and Einstein gravity?

It is perfectly true that Einstein’s special theory of relativity, published in 1905, reveals the speed of light as the ultimate speed limit of any material body.

However, the problem with special relativity is that it is... special!

It relates what one person sees when they look at another person moving at constant speed relative to them.

The moving person appears to shrink in the direction of their motion while their time slows down: effects that become ever more marked as they approach the speed of light.

But most of the time bodies change their speed with time – for instance, a car accelerates away from traffic lights.

With the general theory of relativity, published in 1915, Einstein extended special relativity, relating what one person sees in the general case when they look at another person accelerating relative to them.

The theory fortuitously turned out to also be a theory of gravity, which can be applied to the biggest gravitating system of all – the Universe.

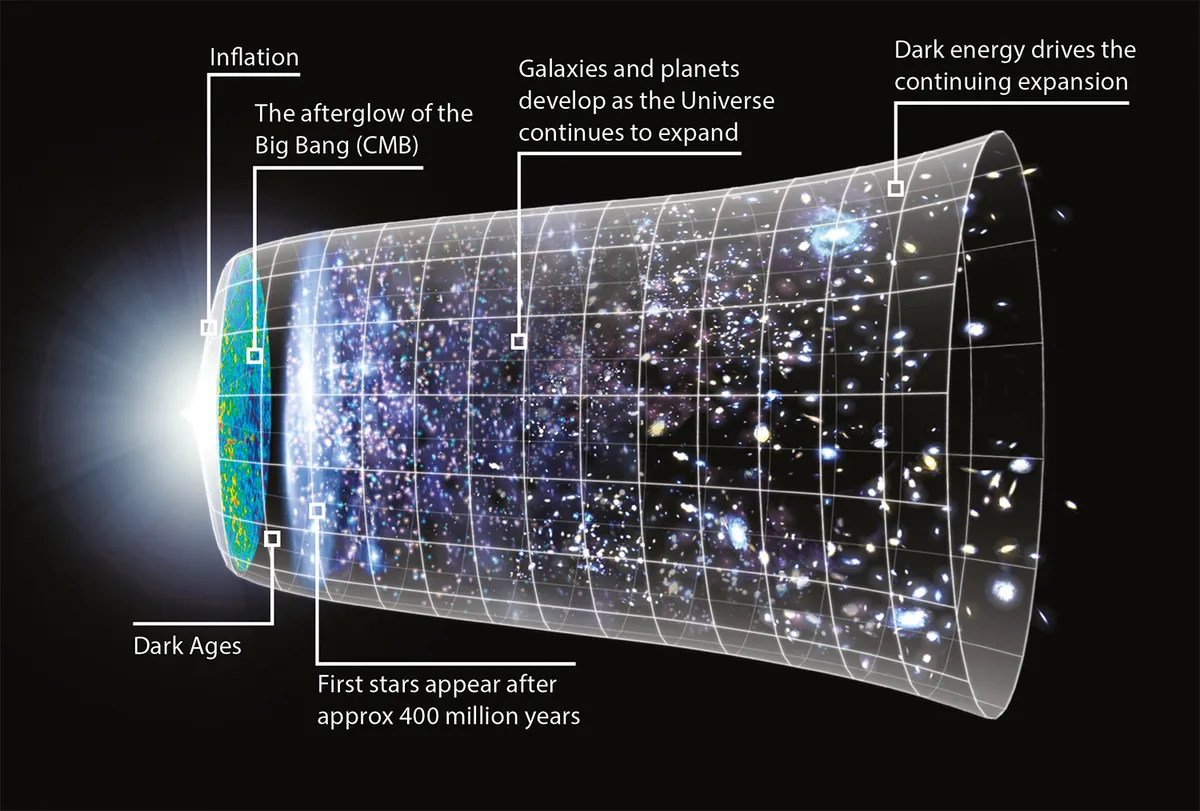

And, when it is, it reveals spacetime to be a kind of backdrop to which the galaxies are effectively nailed.

That ‘backdrop’ – not being a material thing – can expand at any rate it likes. And it certainly did.

That was during the epoch of inflation, during the first split-second of the Universe’s existence, when the expansion of the Universe occurred at a rate that was effectively far faster than the speed of light.

This article originally appeared in the February 2008 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.