While the Galileo spacecraft was looping around the Jovian system in the 1990s it detected something very strange about two of the larger moons.

Galileo was equipped with a magnetometer, an instrument for measuring magnetic fields, a bit like an extremely sensitive compass needle.

More from Lewis Dartnell

And every time the spacecraft performed a flyby of Galilean moons Europa or Callisto, it sensed the field lines of Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field draping around the moons.

The satellites seemed to possess a weak magnetic field that was interacting with that of Jupiter.

These tiny, frozen moons can’t have been generating the magnetic field themselves by an active internal dynamo, as happens in Jupiter and Earth’s molten metal cores.

It was being created indirectly, as the moons moved through Jupiter’s own field.

In order for this induced magnetic field to arise, there must be a layer of something hidden beneath the frozen face of the moons that is electrically conductive.

By far the most likely option was salty water – Europa and Callisto both harbour subsurface oceans, and it is these that are interacting with Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Detecting oceans on the moons of the Solar System

This same technique could be used to remotely sense the presence of subsurface oceans on other moons too.

Corey Cochrane at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and his colleagues argue that Uranus and Neptune also offer a great opportunity for using magnetic sounding to detect oceans within their moons.

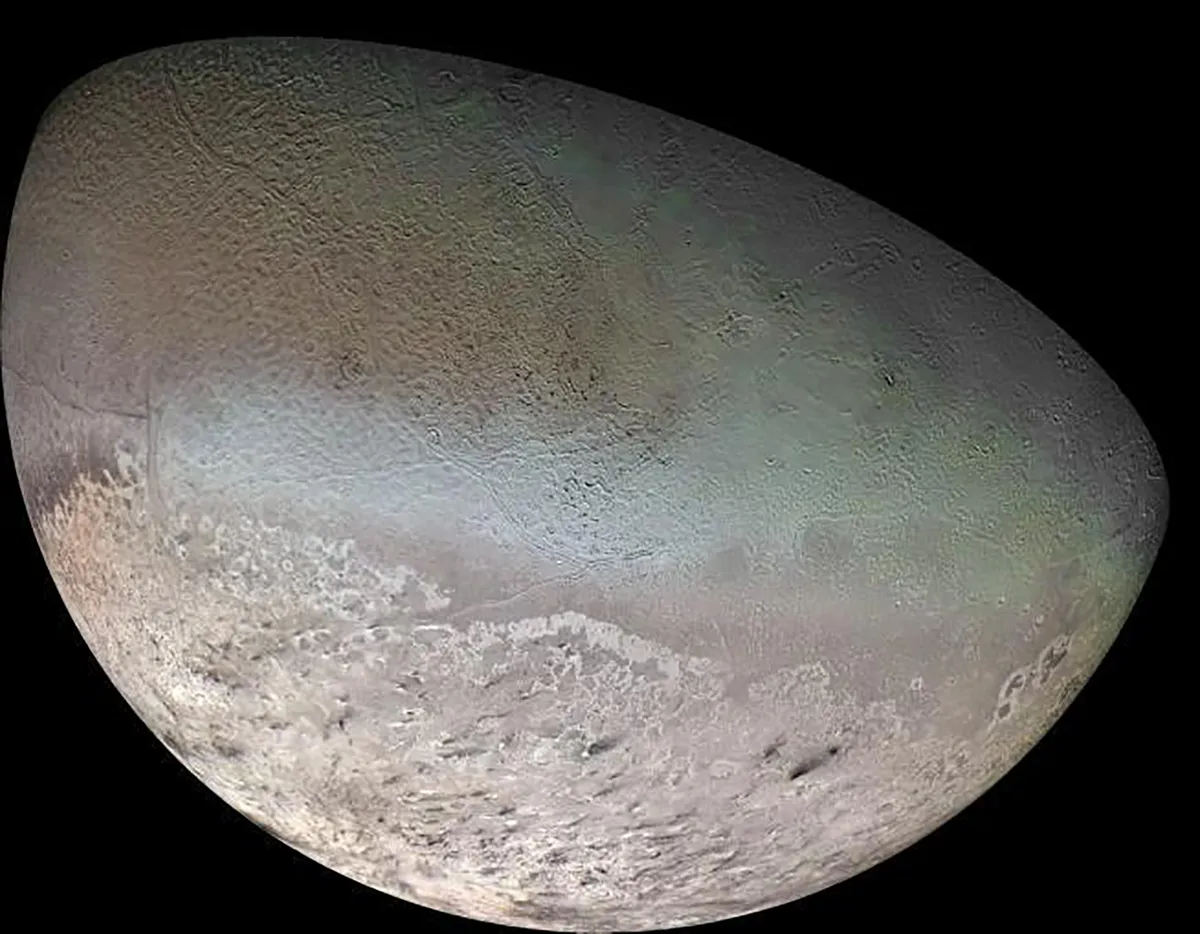

Neptune has only one major moon, Triton, which is thought to be a captured Kuiper Belt Object that destroyed Neptune’s original system of satellites when it arrived.

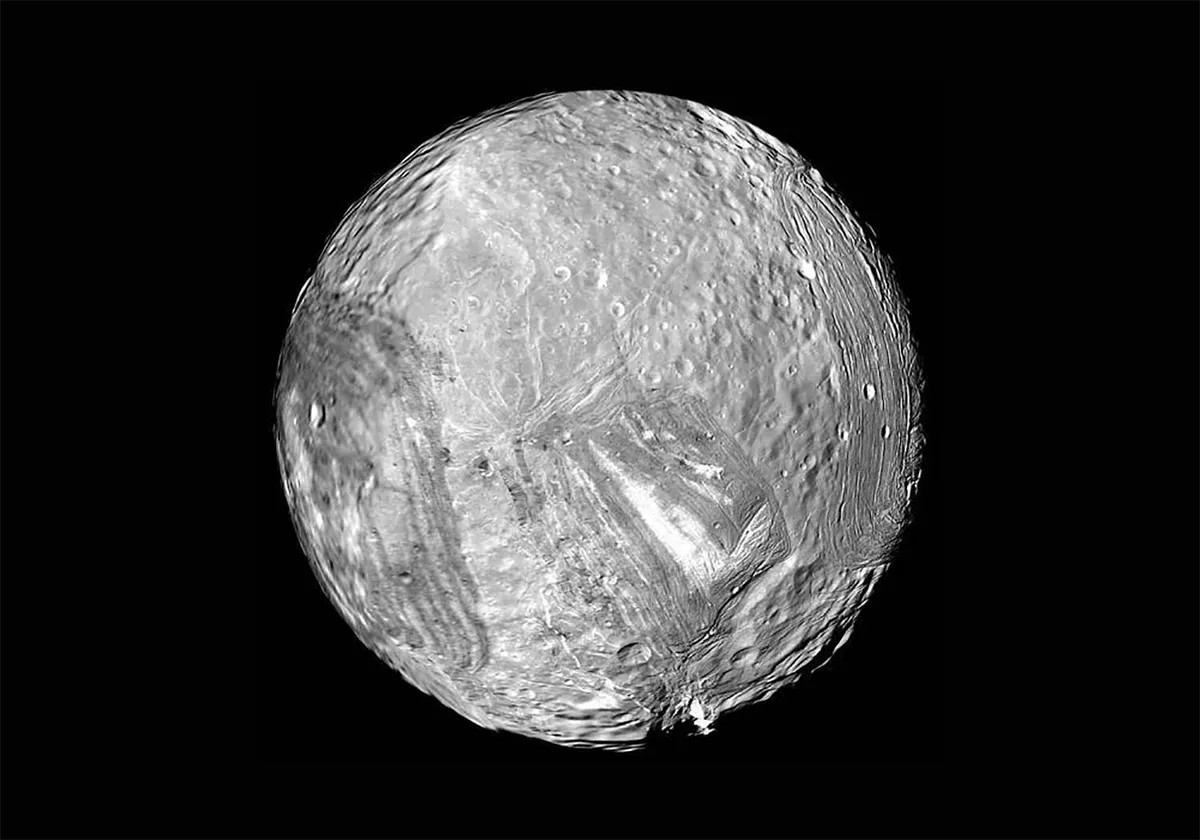

Uranus has a diverse family of moons (named after Shakespearean characters), including Puck, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel and Oberon.

Voyager 2 visited both the Uranus and Neptune systems, but it didn’t pass close enough to any of the moons to detect the tell-tale signature of magnetic induction.

Photographs taken by the probe, however, show widespread evidence in the landscapes on both Miranda and Ariel of recent tectonic and cryovolcanic activity.

Perhaps these moons have subsurface liquid water oceans that persist even today.

And Cochrane says that available technology could readily detect such oceans with just a single flyby.

What’s more, Uranus’s quirky magnetic field would allow a probe to deduce a great deal about a subsurface ocean.

The ice giant’s magnetic field is not only pretty intense, but crucially is tilted significantly relative to the orbits of the major moons – by around 60° – and is also offset from the centre of the planet.

The planet’s satellites experience a magnetic field that is constantly varying. The induction effects of this within the moon’s interior mean that researchers could even start working out the depth, thickness and conductivity of different subsurface layers.

Lewis Dartnell was reading In Search of Subsurface Oceans within the Uranian Moons by CJ Cochrane et al. Read it online at arxiv.org.

This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.