Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch astronomer, first hypothesised the existence of Venus’s atmosphere in 1698 when he observed the planet through his telescope.

Despite viewing its waxing and waning phases, he could not see any features on its surface and guessed that a thick atmosphere must be obscuring his view.

Years later in 1761, Russian Mikhail V Lomonosov detected the refraction of solar rays while observing the transit of Venus across the Sun – and thus discovered the atmosphere of Venus.

Find out what makes Venus so special and why Venus spins backwards

Facts about Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and our nearest planetary neighbour.

It has a rocky body similar in nature to Mercury, Earth and Mars.

Named after the goddess of love and beauty, and described as Earth’s twin, Venus is only 638.4km smaller in diameter than Earth and has a similar mass.

Despite being further from the Sun than Mercury, Venus is the hottest planet in the Solar System.

Surface temperatures on Venus reach a scorching average of 475°C, a stark contrast to Earth’s average of 15°C.

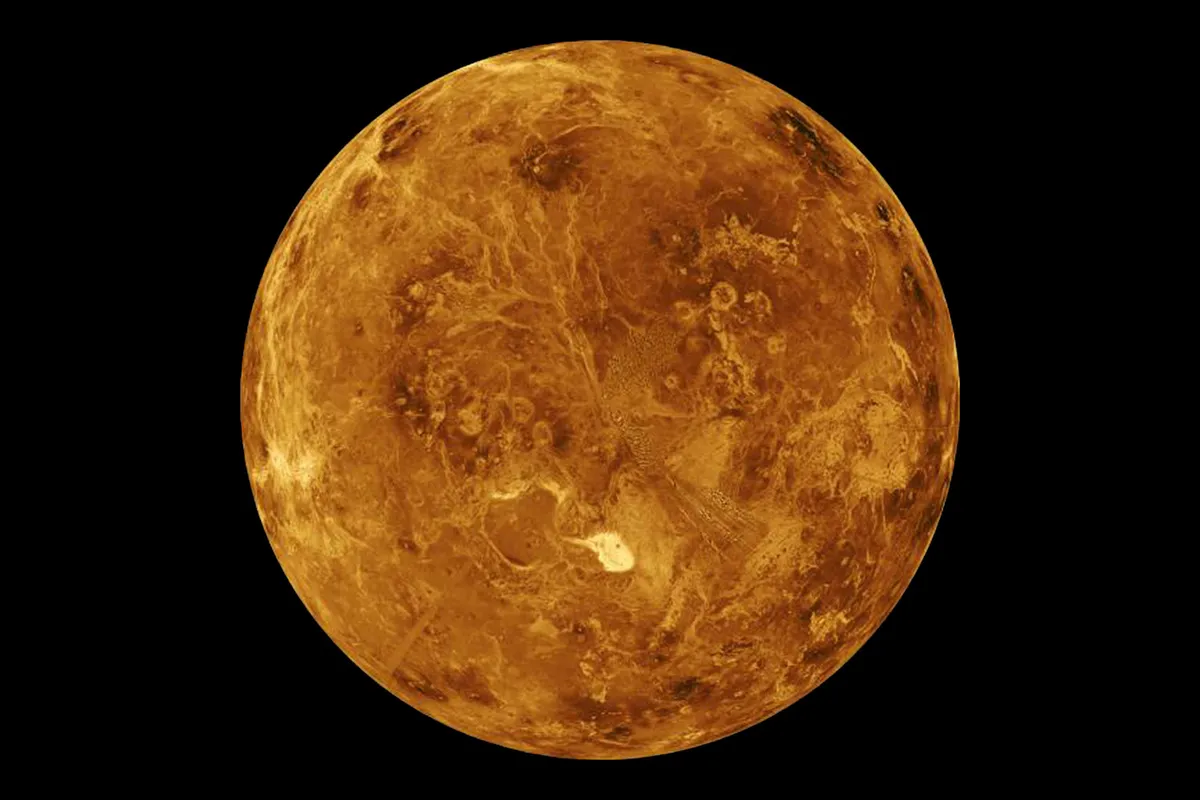

It’s theorised that 4 billion years ago, Venus’s atmosphere was like Earth’s, but today has a dense atmosphere composed of 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen and the remainder made up of trace elements including sulphur dioxide.

It’s believed that early volcanism released carbon dioxide into the atmosphere on both Earth and Venus.

But while our planet’s plate tectonics helped to recycle this back into the rock, Venus was unable to do so.

The carbon dioxide simply built up in the atmosphere.

This locked the planet into a runaway greenhouse effect, where the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere blocks thermal radiation from exiting the planet, resulting in high temperatures and explaining why Venus is hotter than Mercury.

If someone were unlucky enough to stand on Venus’s surface, they would experience a pressure over 90 times Earth’s – the equivalent of being 3,000 metres below the ocean.

Perhaps Venus can tell us a lot about the effects of climate change on Earth.

Venus atmosphere and the night sky

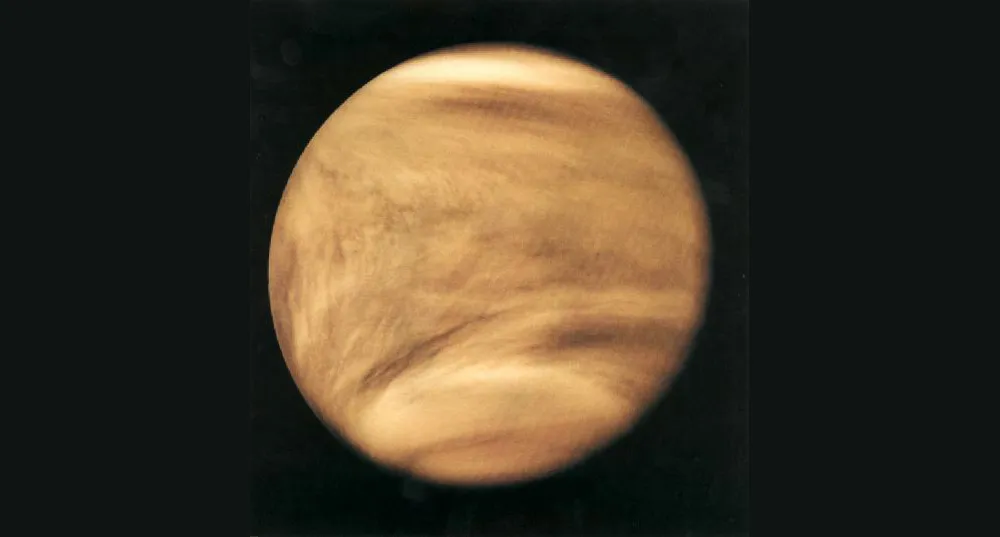

Venus’s atmosphere also makes it the third-brightest object visible with the naked eye.

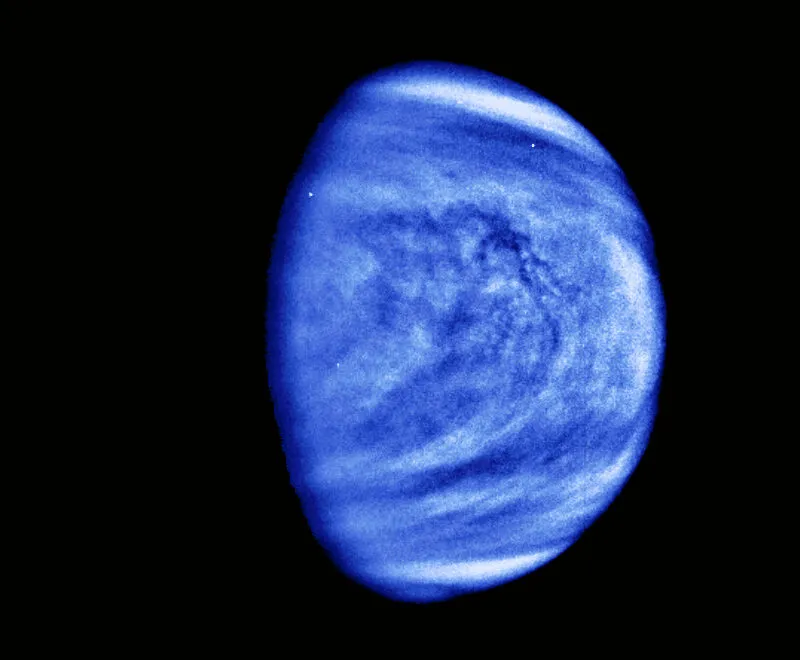

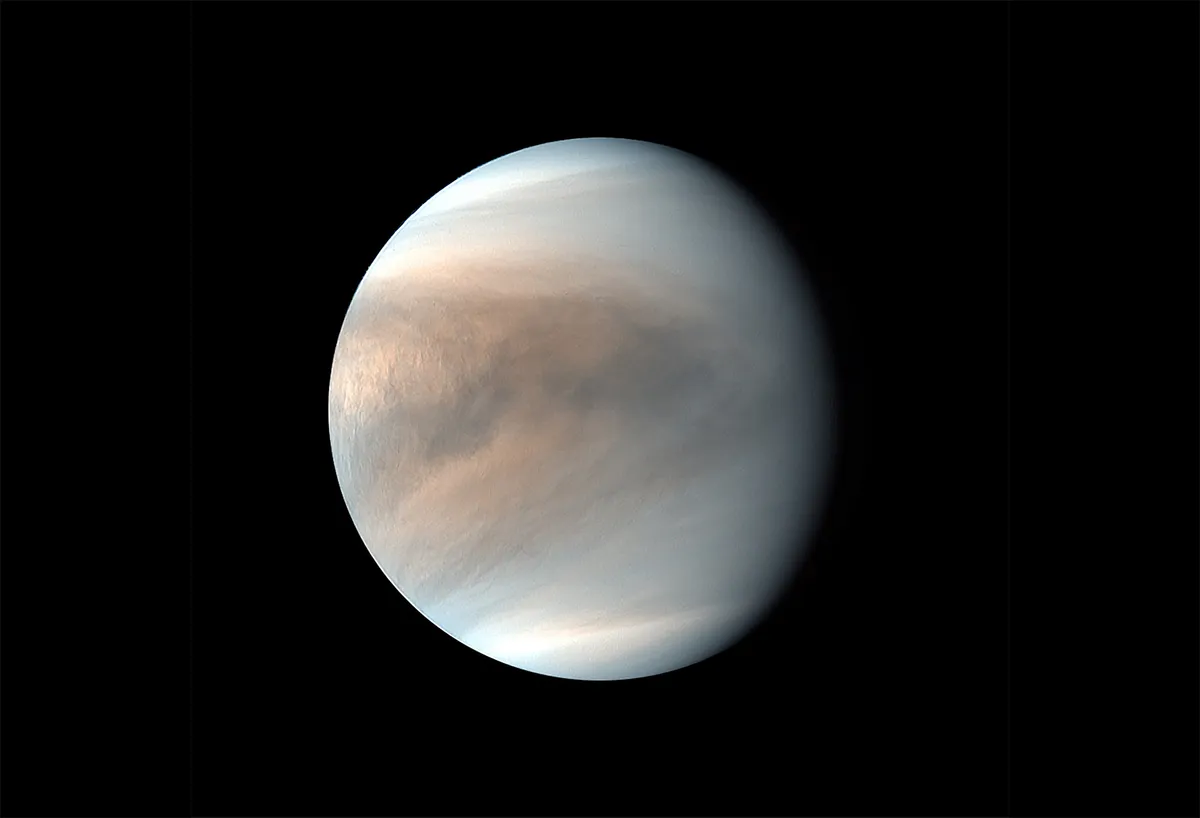

Dense clouds composed of sulphuric acid cover the planet, preventing sunlight penetrating through to the surface.

These clouds reflect up to 84% of the incoming rays from the Sun, causing it to outshine most night-sky objects.

The clouds race around the planet in days, blown by powerful atmospheric winds of around 300km/h, releasing droplets of sulphuric acid that evaporate before reaching the planet’s surface.

Spacecraft that have visited Venus

The information we have about Venus’s atmosphere today is credited to the many missions sent to Venus.

In 1962, Venus became the first planet to be visited by spacecraft, when NASA’s Mariner 2 flew within 34,854km of the planet.

Since then, nearly 40 missions have visited Venus.

After several fly-bys throughout the 1960s and 1970s following Mariner 2, NASA mounted the Pioneer Venus project to enter the planet’s atmosphere.

NASA Pioneer

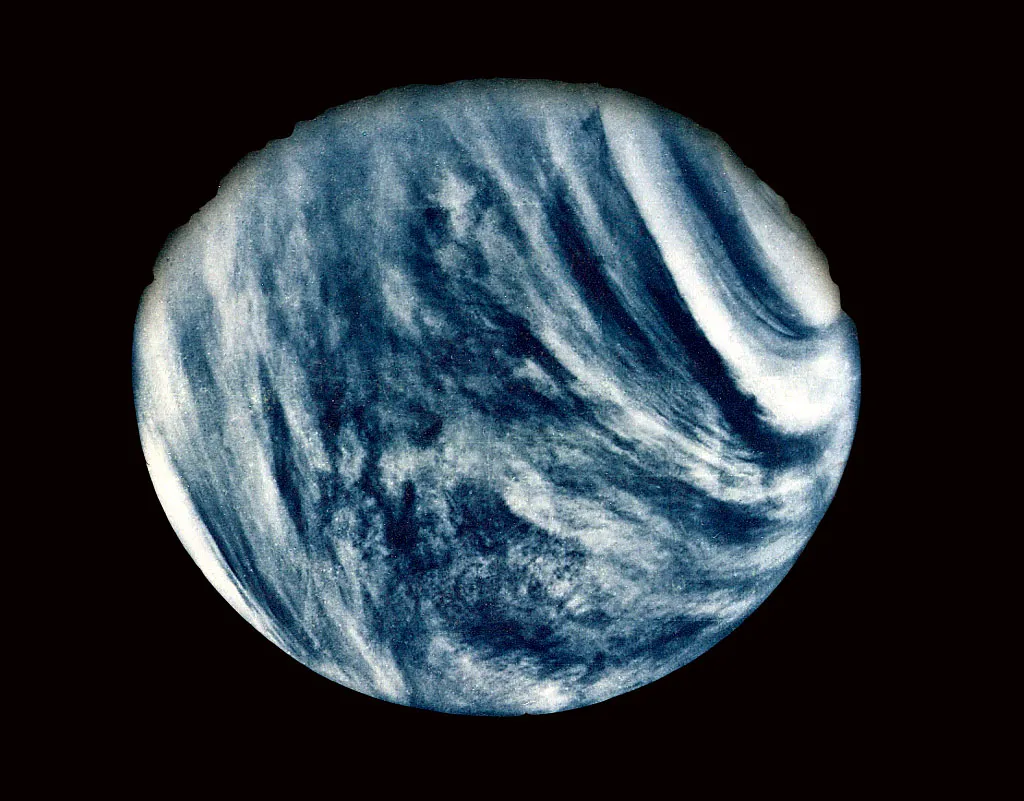

1978 saw the launch of NASA’s Pioneer Venus mission and the Soviet Venera 11 and 12, all of which collected data about the planet’s hostile atmosphere.

In December 1978, Pioneer Venus entered orbit around the planet before deploying the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe (also known as Pioneer Venus 2), containing four smaller probes, into the atmosphere.

The orbiter continued to operate until 1992.

Crucial data recorded during this mission revealed the absence of a magnetic field, extremely high wind speeds and three cloud layers above the surface.

Venera missions

A few weeks later, the French–Soviet Venera 11 and 12 missions arrived.

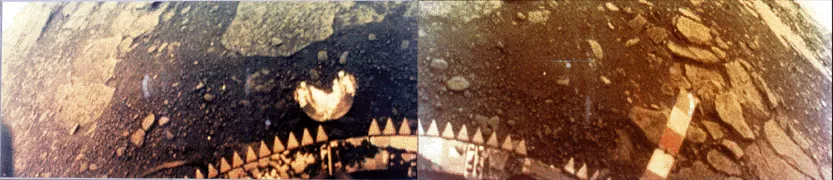

From 1961 to 1983, the Soviets sent 13 spacecraft into the planet’s atmosphere, eight of which – including Venera 11 and 12 – survived to transmit from the surface.

The main aim of these missions was to take colour photos of the surface of Venus, but unfortunately the camera lens caps failed to open once on the surface.

Still, crucial atmospheric data was captured, including evidence of thunder and lightning, and low levels of carbon monoxide at low altitudes.

In recent decades, most spacecraft have only snapped a quick view of Venus as they sped by on their way elsewhere, though a handful – including NASA’s Magellan and ESA’s Venus Express – stayed for a longer look.

The Japan Space Exploration Agency's (JAXA) Venus Climate Orbiter 'Akatsuki' has been tasked with learning more about the atmosphere on Venus.

Launched on 20 May 2010, it became the first Japanese probe to enter orbit around a planet other than Earth on 7 December 2015.

Interest is beginning to grow again, and now three new missions are currently being planned, a potential renaissance for this most hostile of worlds.

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine