There's water on Mars, isn't there?

It feels like several times a year the latest discovery of water on Mars is announced, yet images sent back by rovers and orbiters show the Red Planet as an arid, inhospitable desert.

The ‘discovery’ of water on Mars has happened so many times you’d be forgiven for thinking that the Red Planet is wetter than a Bank Holiday weekend

So what do we actually know about the waters of Mars, and will they be of any use to us in the future?

Early astronomers got it wrong

Early astronomers believed some strange things about Mars.

Long before the birth of the Space Age, there were a great many people who firmly believed that water flowed on the Red Planet.

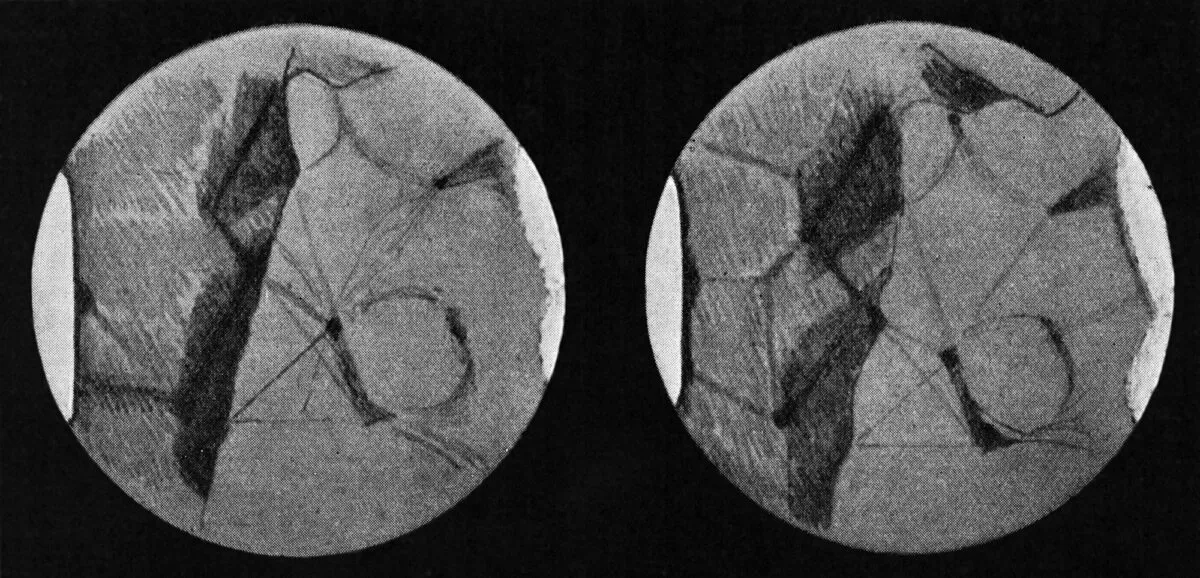

They knew Mars was probably a lot colder than Earth because it was further from the Sun, but they were sure Mars’s water was liquid because through telescopes they saw dark areas that changed size over the seasons.

Believing these to be patches of vegetation, they assumed that there must be water to irrigate them.

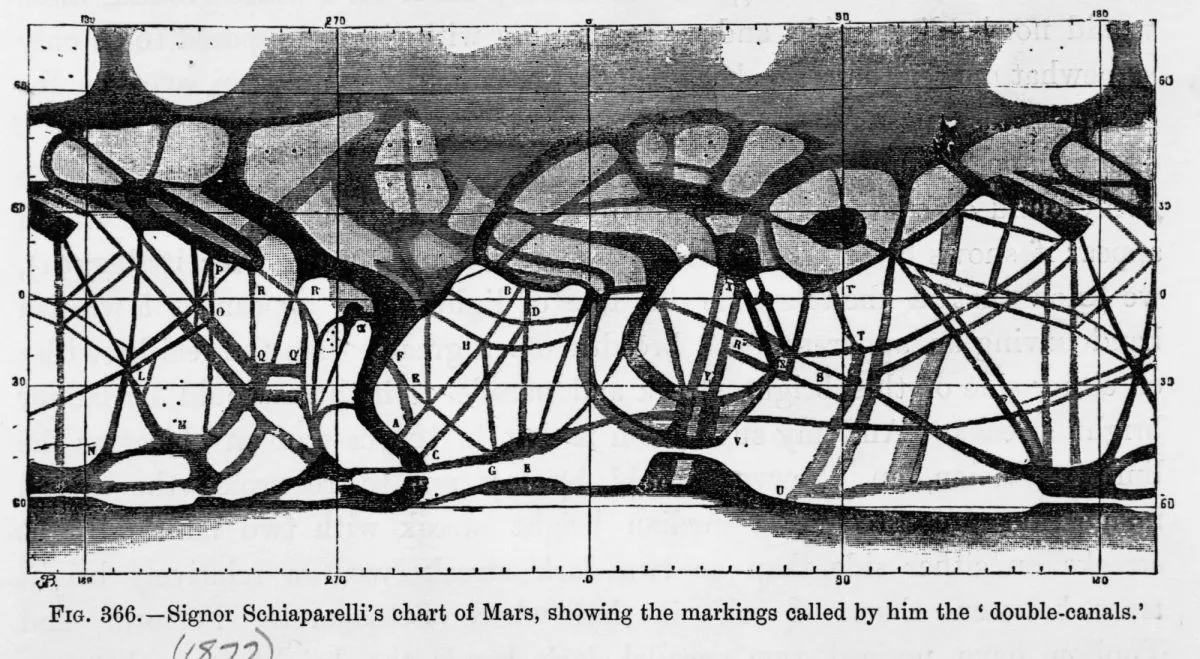

Astronomers like Percival Lowell (1885–1916) claimed to have observed a network of straight lines crisscrossing Mars and, adding 2 + 2 to get 100, he declared they were canals dug out of the ground by Martian navvies to carry precious water from the poles to thirsty cities.

Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images

Mars’s hidden oceans

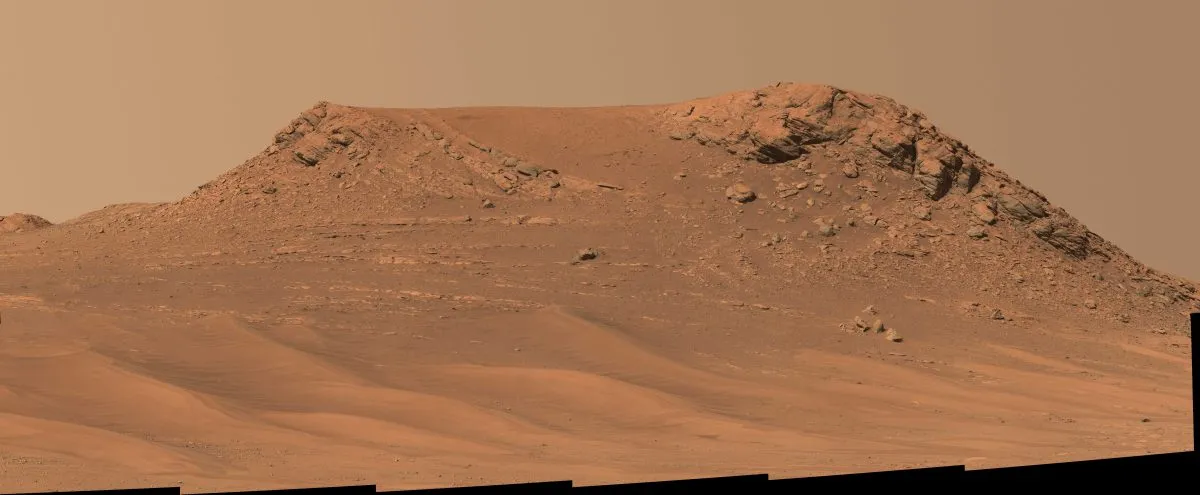

NASA’s Mariner 9 sent back its first images in 1971 showing Mars was a frozen, cratered wasteland.

The seasonal patches of vegetation were just vast fields of fine dust, blown away by seasonal winds to reveal the dark surface beneath, and the canals were nowhere to be seen.

Mars had no water, it was a dust bowl, drier and deader than the most arid desert on Earth.

But today, thanks to space missions that followed Mariner, we know that there is water on Mars.

It’s just not found on the surface in the liquid form we’re most familiar with here on Earth.

When human explorers eventually reach Mars, if they want to use its water, they’ll have to dig.

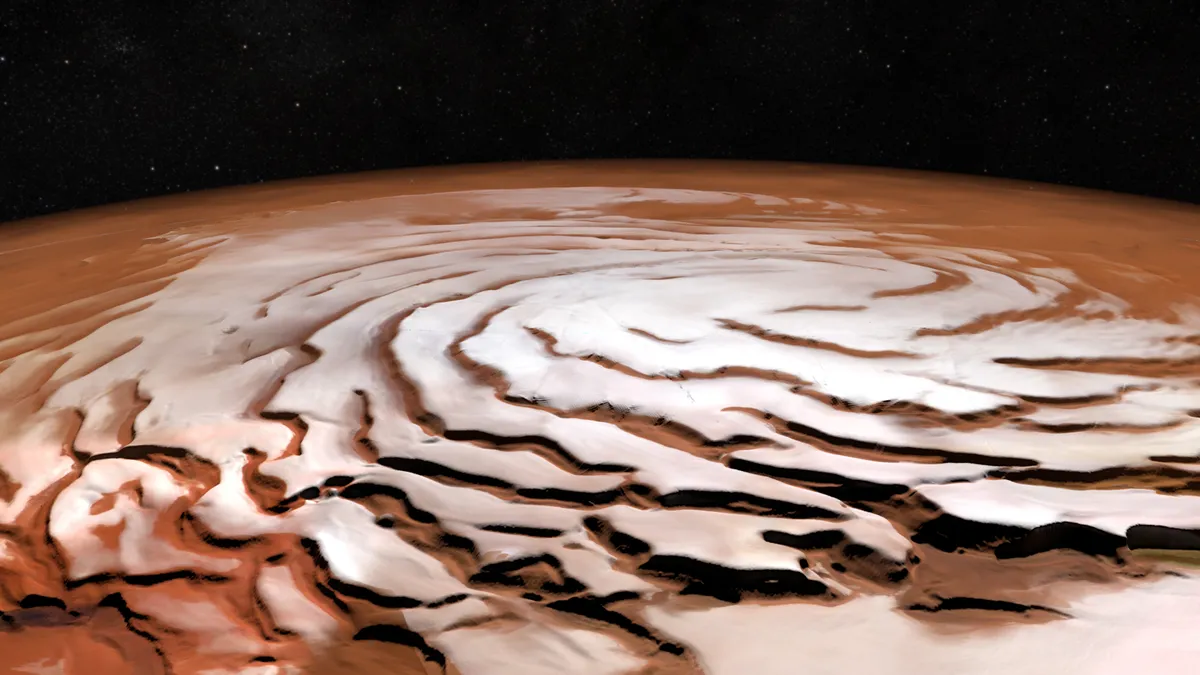

Large amounts of water ice have been discovered at the Red Planet’s poles and beneath its surface at mid latitudes.

But this isn’t clean ice you could plink into a drink on a hot day.

Like the ice found in permafrost here on Earth, this Martian ice is so thoroughly mixed up with dust and dirt that the only way to release its water would be to heat up the dirty material and melt it out.

There is deeper water too.

While nuclear-powered rovers were busy photographing Mars’s stunning landscapes and skies, NASA’s solar-powered InSight lander’s mission was to explore the interior structure of Mars using seismology.

Over four years its sensitive instruments recorded ‘marsquakes’ travelling through the planet, which suggested the existence of large reservoirs of liquid water deep within the Martian crust.

However, at depths of 11.5 to 20 kilometres (7 to 12 miles), these reservoirs will not be easily accessible to future explorers and settlers.

Where did Mars's water go?

While images from spacecraft in orbit around Mars show us that Mars is dry today, they also prove that it was much wetter in the past.

These pictures show meandering dried-up channels where water once flowed across the landscape, and even the shoreline of an ancient ocean that once covered much of the Red Planet’s low, northern hemisphere.

So if you jumped in a time machine and fell several billion years backwards through time, you’d probably see a very different Mars to the one we see today.

Ancient Mars would probably be a beautiful blue world much like our own, with rivers and streams flowing into a great northern ocean, all beneath a pale blue sky painted with fluffy white clouds.

So where did all Mars's water go?

Over time, much of it was lost to space.

Mars’s weak magnetic field and low gravity allowed the solar wind to strip away its atmosphere, causing its water to slowly evaporate into space, leaving it dusty and dry.

What Martian water remains today is either frozen into the ground or lies underground, having fallen through cracks in the surface rocks.

Why we need water on Mars

Why is the existence of water on Mars, in any form, so important?

Because it could be used not just to drink but to break down into hydrogen and oxygen, to make fuel and air, both of which will be essential resources for the establishment and survival of permanent bases on the Red Planet.

And of course, wherever there is water on Earth we find life, so it’s possible that primitive life might exist in these watery environments on Mars too.

This article appeared in the January 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine