Early in 2023, astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope announced they had discovered a set of ‘Universe-breaking’ galaxies could upend our ideas about how galaxies are born.

JWST is able to observe galaxies that are so distant, we’re seeing them as they were just 500–700 million years after the Big Bang, giving a window into the epoch when galaxies were just beginning to form.

These were all expected to be small, infant galaxies just beginning to grow, so astronomers were shocked to find six that appear to have comparable masses to the Milky Way.

"This is our first glimpse back this far, so it’s important that we keep an open mind about what we are seeing," says Joel Leja from Penn State University, who took part in the study.

"The amount of mass we discovered means that the known mass in stars at this period of our Universe is up to 100 times greater than we had previously thought. Even if we cut the sample in half, this is still an astounding change," says Leja.

"The revelation that massive galaxy formation began extremely early in the history of the Universe upends what many of us had thought was settled science."

To find out more about how these Universe-breakers were discovered, and what it means, we spoke to Erica Nelson, an assistant professor of astrophysics at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was part of the study.

What was the early Universe like?

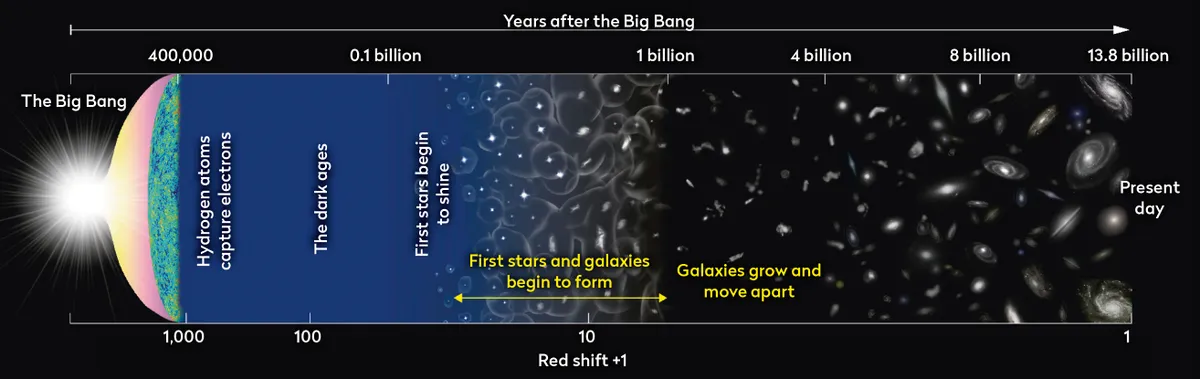

In the beginning there was nothing: no time, no space. Then the Big Bang happened and everything popped into existence – all the light and matter that exists in our Universe.

The early Universe was a hot, dense, turbulent place and the kinds of objects that could form then were very different from those that could form today.

What was your research team looking for?

We were trying to see the first luminous objects in the Universe.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was constructed to look back at the earliest cosmic epochs to search for these luminous objects. We don’t yet know how far back in time they exist.

We didn’t think JWST would have the sensitivity to see individual stars, so instead we were looking for galaxies that are much more luminous.

How did you make your discovery?

I was blinking back and forth between Hubble Space Telescope images and JWST images and noticed these fuzzy spots that were extremely red, bright and didn’t exist in the Hubble images.

We started trying to figure out what they were.

We were analysing the data and found that one was a massive galaxy, very early in the Universe.

Our collaboration then found more of these objects that looked like galaxies.

What era did these galaxies exist in?

The earliest is about 500 million years after the Big Bang.

These early galaxies had the same number of stars as our Milky Way, shortly after the first stars formed.

In comparison, our Milky Way has had 14 billion years to form: the entire history of the Universe.

Did you expect to see such galaxies?

We have theories of cosmology, one of which says the Universe began with a Big Bang 14 billion years ago.

This theory makes predictions for how big galaxies should be able to get at a given era in the Universe’s history.

Based on those predictions, we did not think galaxies should exist at such early times as we discovered them; it’s not possible in current theories of cosmology.

We call these galaxies the ‘Universe breakers’ because they shatter the notion that massive galaxies took billions of years to form, a fundamental precept of our understanding of the Universe.

What’s next for researchers looking for these ‘Universe breakers’?

First, we need to validate that one or more of these objects is a galaxy, because we’ve never seen such objects before.

We’d also like to find more of them to determine if this is some kind of statistical anomaly; the Universe is big and the patch of sky that we looked at is small.

The second is that we need to get more JWST data on these objects, mainly spectroscopic data, and that will tell us if they’re real.

How will spectroscopic data confirm they'regalaxies?

Everyone says that an image is worth a thousand words but for us, a spectrum is worth a thousand images.

With a spectrum we can tell if the light we see is due to, say, a quasar. It also allows us to confirm how far away these objects are and hence know how old they are.

If they’re not galaxies, what else could they be?

We got additional data on one of the objects in December, and it turns out to be a baby quasar and not a galaxy.

A quasar is a supermassive black hole that is eating the stars, dust and gas around it and converting that mass into energy.

Quasars are incredibly luminous, some of the brightest objects in the Universe – not intuitive, given that they are black holes.

It’s possible that others could be quasars, though we have some evidence to the contrary.

We’ve thought of some exotic possibilities of what they could be, though it would be more exciting if it was something we hadn’t thought about before.

But if even one of them is a galaxy, that would be a challenge to our theories of cosmology.

You can read the full paper at www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-05786-2

This interview first appeared in the June 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.