WASP-43 b is a scorchingly hot exoplanet where temperatures reach nearly 1,250 degrees Celsius (2,300 degrees Fahrenheit) and winds howl at speeds of up to 5,000 miles per hour.

This means the hottest side of the planet is hot enough to forge iron, and what's more, there isn't even any relief in the form of a night and day cycle.

Just like our Moon around Earth, exoplanet WASP-43 b is tidally locked with its host star, meaning one side always faces the star and the other side is always facing outwards into the cosmos.

Not that this provides much relief for the permanent night side of the planet: despite its relative coolness, it still reaches temperatures up to 600 degrees Celsius (Fahrenheit).

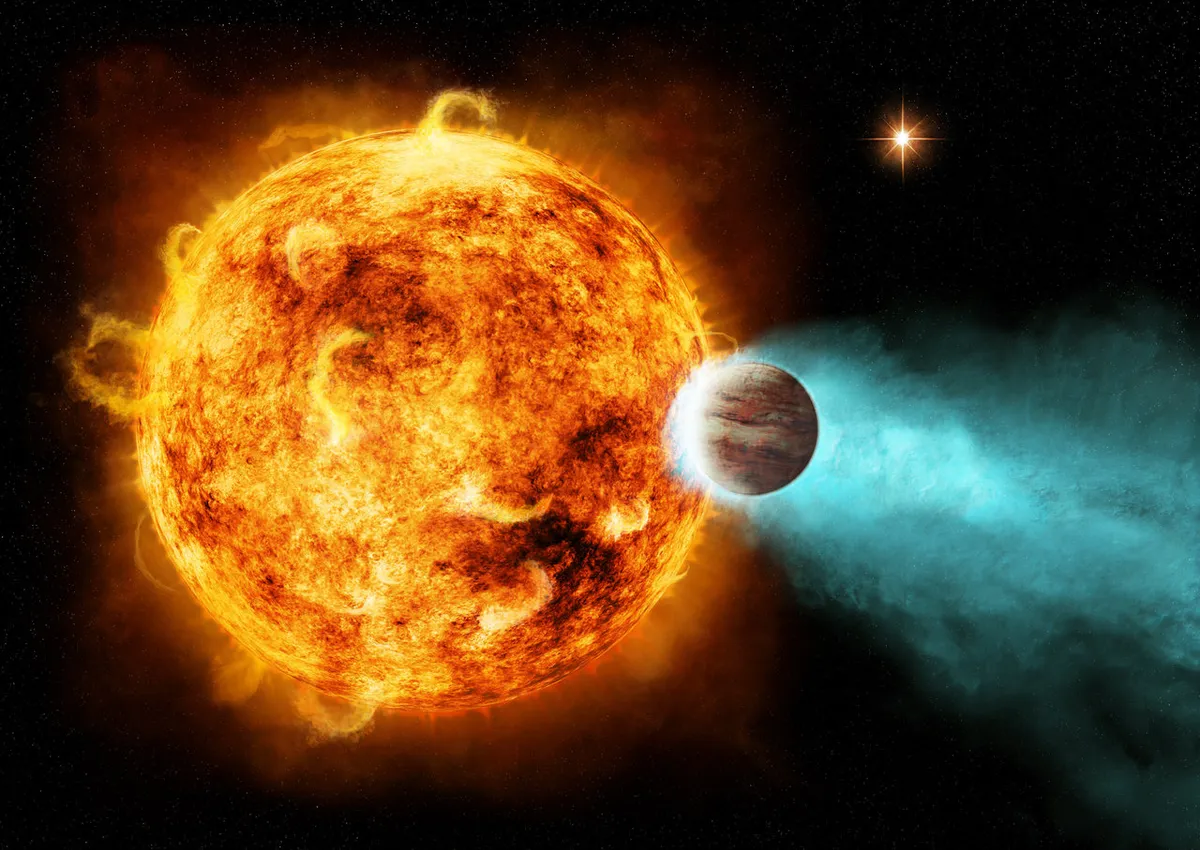

These extreme temperatures are a result of WASP-43 b being a hot Jupiter exoplanet, which means it's a large gas giant planet like Jupiter but orbits much closer to its host star than Jupiter does to our Sun.

Even though the star is smaller and cooler than our Sun, exoplanet WASP-43 b orbits at a distance of just 1.3 million miles. That's less than 1/25th the distance between Mercury and the Sun.

Find out more about how the Webb Telescope studies exoplanets

Weather forecasting on WASP-43 b

These incredible discoveries are the result of a study by a team of astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope to map weather on the exoplanet.

They used brightness measurements over a broad spectrum of mid-infrared light, 3D climate models and previous observations from other telescopes to discover thick, high clouds covering the nightside of WASP-43 b.

On the dayside they found equatorial winds blowing at 5,000 miles per hour, churning atmospheric gases around the exoplanet.

As well as the scorching temperatures on the dayside and nightside of the planet, the data also revealed the hottest spot on WASP-43 b, which is just east of the point that receives the most stellar radiation

WASP-43 b was discovered in 2011 and has been observed with telescopes including the Hubble Space Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope.

You can read all about Hubble's observations of WASP-43 b here.

"With Hubble, we could clearly see that there is water vapour on the dayside. Both Hubble and Spitzer suggested there might be clouds on the nightside," says Taylor Bell, researcher from the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute and lead author of a study published in Nature Astronomy.

"But we needed more precise measurements from Webb to really begin mapping the temperature, cloud cover, winds, and more detailed atmospheric composition all the way around the planet."

How the map was made

WASP-43 b is too small, dim and too close to its star to be directly observed. So how do you study a planet you can't even see?

The astronomers used a technique called phase curve spectroscopy, a which involves measuring minuscule changes in brightness of the star-planet system as the planet orbits the star.

Brightness data captured by Webb was then used to calculate the planet’s temperature.

Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) measured light from the WASP-43 system every 10 seconds for over 24 hours.

"By observing over an entire orbit, we were able to calculate the temperature of different sides of the planet as they rotate into view," says Bell.

"From that, we could construct a rough map of temperature across the planet."

The astronomers used 3D atmospheric models, just like those used to measure weather and climate on Earth, to make their analysis of WASP-43 b.

The study reveals how the nightside of the hot Jupiter exoplanet is covered in thick clouds that prevent some of the infrared light from escaping, which is why the scorching nightside looks cooler in infrared light.

Water and winds

The team were also able to use their data to measure water vapour and methane on the planet.

They found clear evidence of water vapour on the nightside and the dayside of the planet.

But the data shows a lack of methane in the atmosphere.

"The fact that we don't see methane tells us that WASP-43 b must have wind speeds reaching something like 5,000 miles per hour," says Joanna Barstow, a study co-author from the Open University in the UK.

"If winds move gas around from the dayside to the nightside and back again fast enough, there isn’t enough time for the expected chemical reactions to produce detectable amounts of methane on the nightside."