The modern understanding of Mars is the result of over 50 years of exploration by robotic spacecraft. However, before the Space Age, Earth-bound astronomers had forged a long history of observing the Red Planet and had forged quite a different picture.

Missions like NASA's Perseverance rover hope to answer some longstanding questions about whether life once existed on Mars, but humanity's view of the Red Planet was once entirely different.

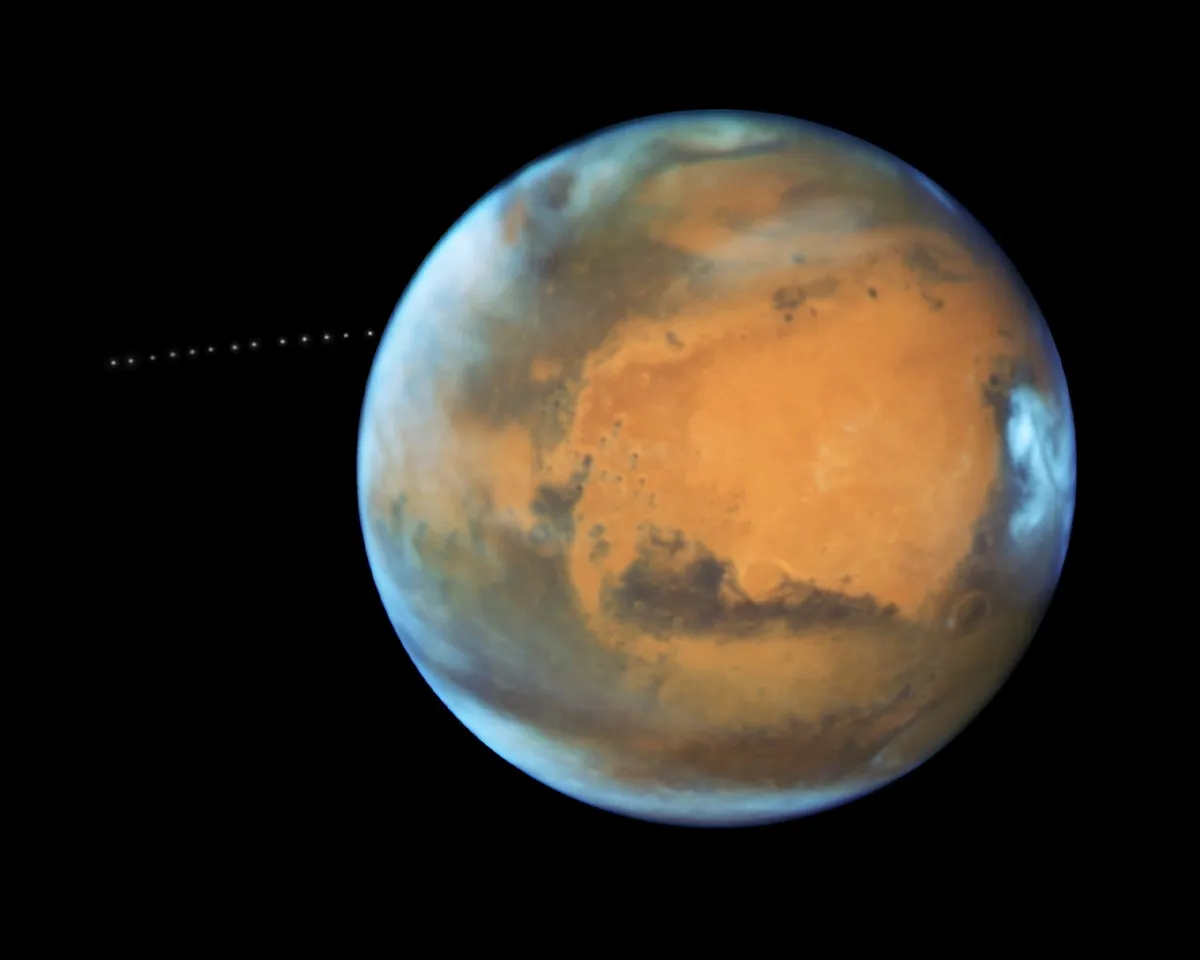

Mars, of course, is a naked-eye planet and has been known since prehistory. To the unaided eye it is a bright star-like object, but even a small telescope reveals a disc.

By the middle of the 19th century, Mars was understood as a world basically similar to our own.

Read more about Mars

- NASA's Curiosity rover captures a selfie

- Wernher von Braun's forgotten mission to Mars

- How the ExoMars 2020 rover will search for signs of life

Indeed, it seemed to be the most Earth-like of the planets and the most likely to be inhabited. Through a scope its disc is mostly orange with smudges of grey-green marking, mostly in the south.

Though the details change with time, the basic features are permanent.

The orange regions were thought to be continents and the grey-green areas to be seas.

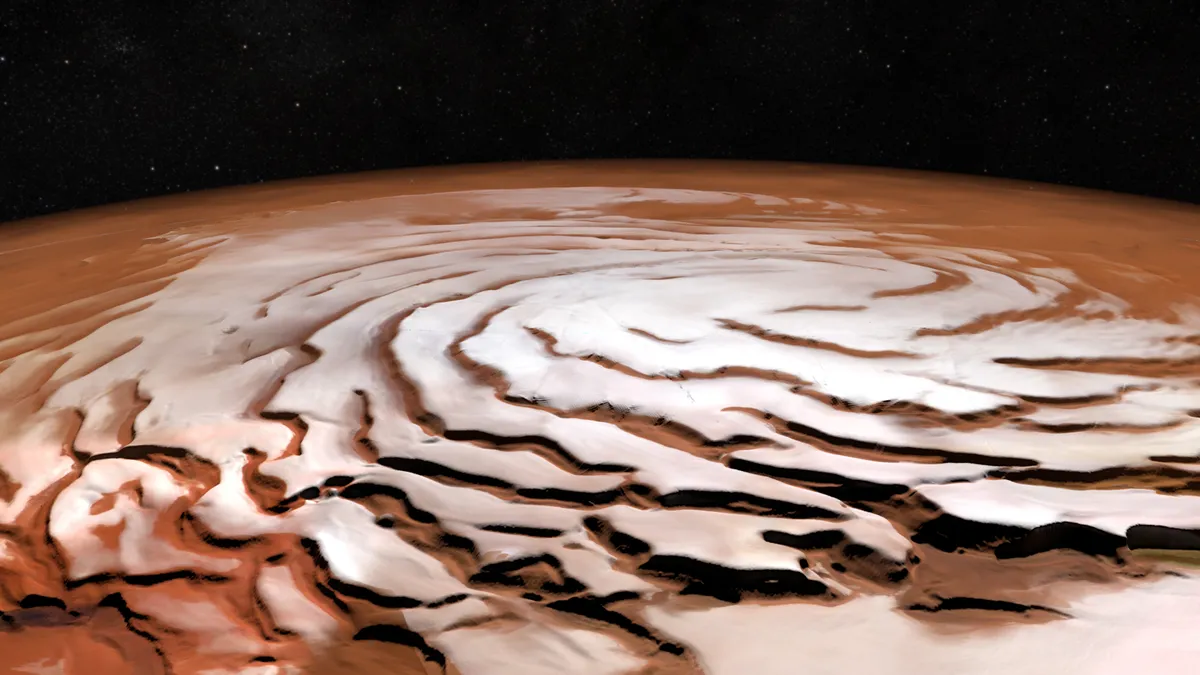

In addition, observers saw white spots at the pole that waxed and waned with the Martian year, implying seasons similar to our terrestrial ones.

The planet seemed to have a substantial atmosphere, which supported occasional clouds.

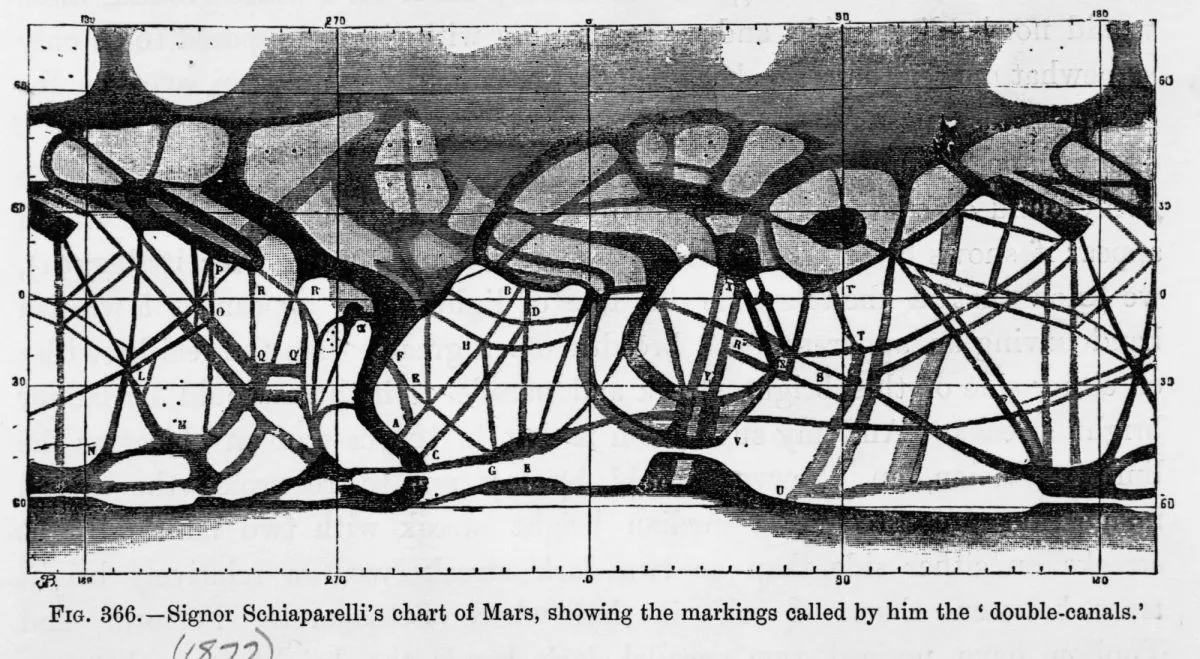

1877 saw a favourable opposition that was well observed, and there were many drawings, sketches and maps subsequently published.

Two maps are particularly noteworthy, one by Nathaniel Green and the other by Giovanni Schiaparelli.

These maps were very different, though both showed considerably more detail than the most comprehensive charts previously available, which had been compiled by Richard Proctor in the late 1860s.

Green’s map was a naturalistic representation with delicate gradations of shading and diffuse borders between the orange and grey-green areas.

Schiaparelli, by contrast, had sharp lines separating the two types of features.

Also, in the northern hemisphere he showed a number of strange, hitherto unsuspected linear features, which he called ‘canali’.

The original Italian could mean either a natural or an artificial waterway, but it was usually translated into English as ‘canal’, thus carrying the implication of an artificial origin, which was plausible as Mars was already thought likely to be habitable.

Schiaparelli himself always remained noncommittal about the origin of the canals.

Others, notably Camille Flammarion - a widely-read French populariser of astronomy - though initially skeptical, later enthusiastically embraced the artificial hypothesis.

Mars’s 1892 perihelic opposition was awaited with widespread interest. One individual whose interest had been aroused was Percival Lowell, a wealthy American businessman, author, traveller and orientalist from Boston.

He was captivated by the artificial canal hypothesis and, with considerable resources at his disposal, founded an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona (where Pluto was later observed for the first time) specifically to study the planet.

Lowell’s Mars differed significantly from earlier incarnations. The grey-green areas were now sparse vegetation in semi-arid areas and the orange areas desert proper.

The canals were a giant civil engineering project built by an ancient civilisation to irrigate their increasingly desert planet with melt-water from the poles.

These ideas, however farfetched, were based in contemporary notions of planetary, biological and even social evolution.

The period from the 1892 opposition until about 1910 saw a ‘canal craze’, in which the idea of canal-building Martians became widespread in popular culture, featuring in countless newspaper and magazine articles, advertisements and even popular songs.

In part this interest was due to Lowell’s forceful advocacy: he was an accomplished author and speaker, writing persuasive, well-argued books and giving sell-out lecture tours.

In addition, a stream of press releases and articles issued from the Flagstaff observatory.

Enthusiasm for the artificial canals hypothesis was always stronger among the public and other academic disciplines (particularly evolutionary biologists) than astronomers.

Some astronomers suspected – correctly as it turned out – that the canals were optical illusions.

Others accepted their reality but considered them to be natural rather than artificial.

However, from about 1909 onwards the canal hypothesis largely fell from favour among most astronomers.

A number of lines of evidence led to this change. It was realised that Mars’s surface atmospheric pressure – then thought to be about a tenth of the terrestrial value – was too low to allow liquid water to exist.

Drawings of canals and speculation about intelligent life continued to appear in newspaper and magazine articles for decades.

This argument is due to Agnes Clerke (who is better remembered as an historian of astronomy) but it was popularised by the biologist and co-discoverer of evolution Alfred Wallace in his book Is Mars Habitable? (1907), written as a riposte to Lowell.

The supposed hydrological cycle, with polar melt-water flowing through the canals to equatorial regions and returning by means unknown simply made no sense, and the rapidity of changes at the poles meant that the total volume of water involved could not be large.

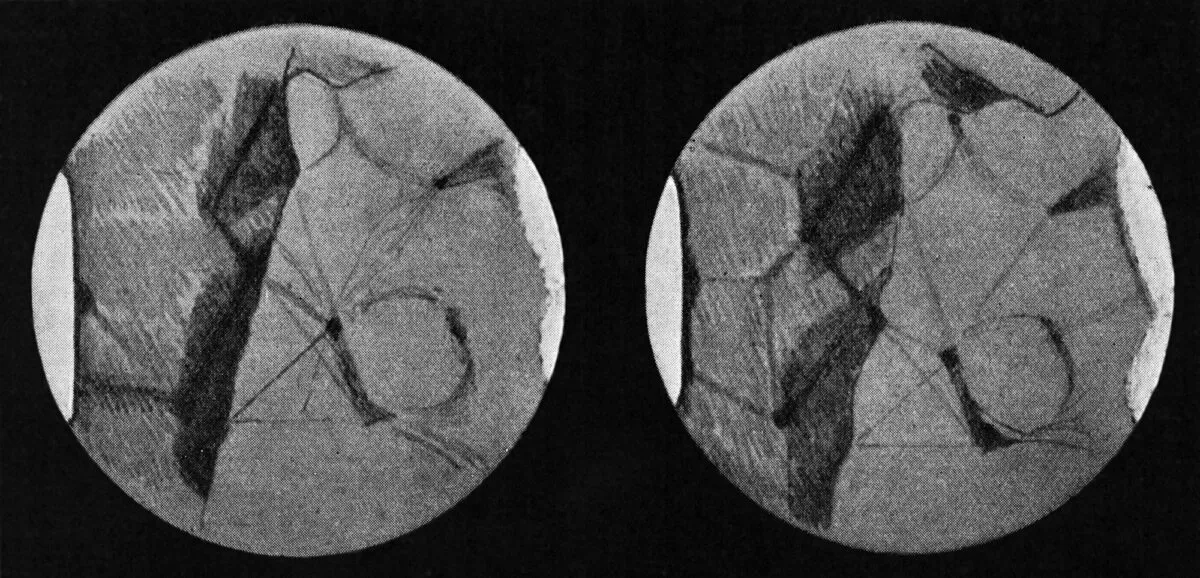

In 1903 Walter Maunder and JE Evans showed that artificial discs covered in random markings presented canal-like illusions when viewed under conditions similar to observing Mars.

Photographs of Mars, first taken in 1905 by Carl Lampland – ironically, at Flagstaff – did not convincingly show the canals.

Spectroscopic measurements by WW Campbell, director of the Lick Observatory, failed to find any water vapour in the Martian atmosphere.

The most persuasive argument, however, came from Eugène Antoniadi, then the pre-eminent Mars observer, who simply failed to see the canals during the 1909 opposition while observing with the Great Meudon Refractor outside Paris.

His testimony was all the more convincing because he had worked with Flammarion and been an exponent of the canals.

Mars in popular culture

All these arguments were contestable, and indeed were contested, but a consensus emerged among the majority of astronomers that the canals simply did not exist.

Mars remained a desert world though, and for succeeding decades it was seen as increasingly inhospitable.

It was still considered plausible that it could support life, but the form such life was believed to take dwindled to nothing more complex than ‘hardy lichen’.

The popular view of Mars, however, simply parted company with the astronomical one and remained firmly fixed in the turn of the century model.

Drawings of canals and speculation about intelligent life continued to appear in newspaper and magazine articles for decades.

The canal craze was also the stimulus for several important early works of science fiction.

In Germany, Kurd Lasswitz’s Two Planets (1897), a nuanced tale of interplanetary contact and conflict, was extremely popular and influenced Wernher von Braun and his circle.

Alexander Bogdanov, a Russian intellectual and revolutionary, wrote Red Star (1908) and Engineer Menni (1913), respectively a simple Martian socialist utopia and a tale of canal construction, which were widely read.

In English, HG Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898) was the prototype tale of interplanetary invasion, while Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (1912) and its many sequels and imitators gave rise to the science fiction sub-genre of ‘planetary romance’ – swashbuckling tales set amidst the royal courts of ancient civilisations, beset by palace intrigues, hostile tribes and fearsome monsters.

These stories were at least as significant as the careful pronouncements of astronomers in framing the public conception of Mars, if not more so.

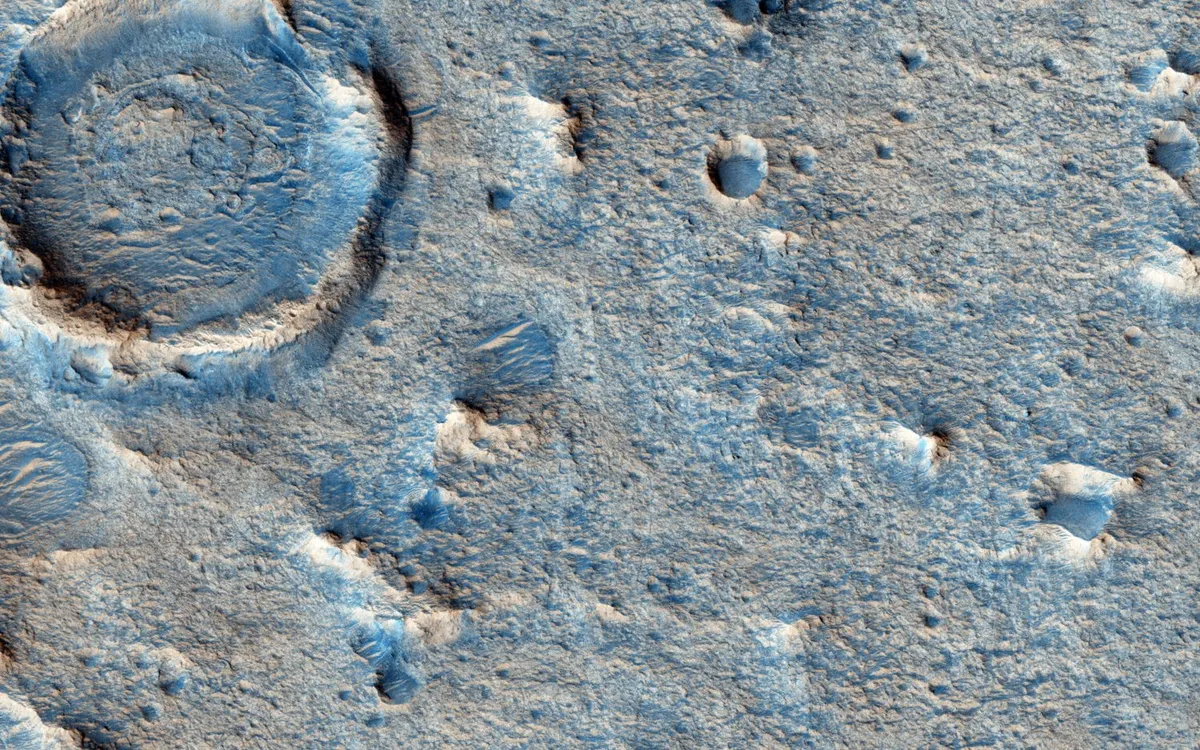

In the event, even the astronomers’ inhospitable Mars proved to be overly optimistic.

The first successful fly-by, by the US Mariner 4 in 1964, returned just 21 grainy, low-resolution black-and-white photographs, but they transformed our understanding of the planet, showing a barren, cratered landscape more reminiscent of the Moon.

The probe also estimated the surface atmospheric pressure to be a hundredth, not a tenth, of the terrestrial value.

Subsequent probes have, of course, swung the pendulum back somewhat, revealing a fascinating world with active geologic processes and perhaps a warmer, wetter past.

Nonetheless, the old Mars was gone forever.

Early observations of Mars

1609-10Galileo Galilei makes the first telescopic observations of Mars. He notes a disc and phases but does not see any markings.

1636Francesco Fontana produces the first Martian sketch to show markings, but they do not correspond with any known surface features.

1659Christiaan Huygens produces the first sketch to show a marking which he called the ‘Hourglass Sea’ – Syrtis Major.

1719Giacomo Maraldi identifies the polar caps and notes that they are neither symmetrical, nor entirely consistent in size.

1783William Herschel confirms the polar caps and their waxing and waning over the year, indicating seasons similar to those on Earth.

Around 1800Johann Schröter produces many sketches of ‘cloud formations’ on Mars that have since been recognised as physical features.

1840Wilhelm Beer and Johann von Mädler become the first to build a series of drawings into a composite map of the whole of the planet.