Today, Galileo Galilei is synonymous with astronomy, scientific martyrdom and the telescope. Galileo was born on 15 February 1564 in Pisa, Tuscanyinto a changing world, one in which the Catholic Church was slowly losing power to Protestantism.

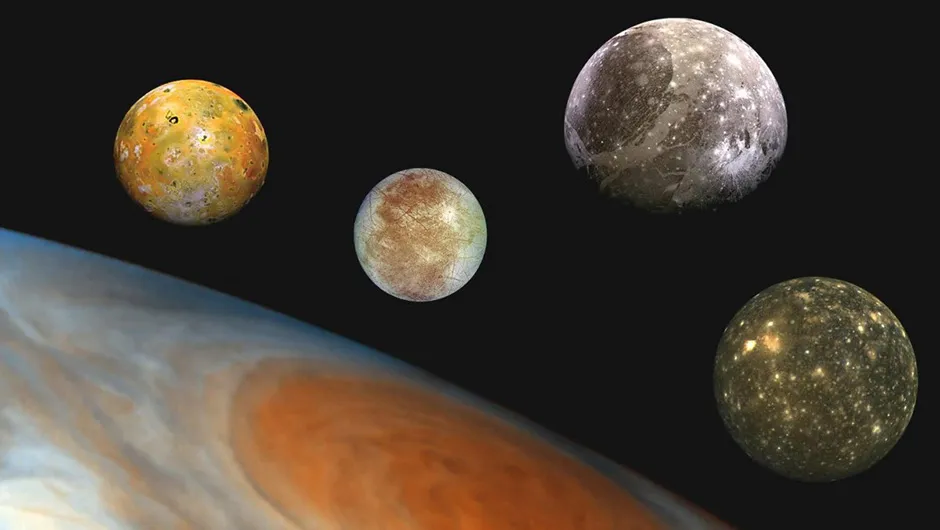

You only have to look at Jupiter, and the four ‘Galilean’ moons that dance around it, to see the mark that Galileo would ultimately leave on astronomy.

But astronomy was not his first love: Galileo was initially taught music, almost became a priest, studied medicine and was eventually appointed a professor of mathematics. It wasn’t until he was 40 that he started studying the night sky.

In the early 17th century, while teaching at the University of Padua, he invented the military compass. This, in a roundabout way, led him to take an interest in another military invention in 1608, one newly arrived from Holland: the telescope.

Galileo’s genius was to turn this military device to the stars and then convince others of the importance of what he was seeing.

Galileo's biggest astronomy discoveries

By 1610, he’d spotted the four moons of Jupiter that would later bear his name. He originally named these moons the ‘Medicean stars’ in a ploy to attract some powerful new patrons, the Medici family, rulers of Florence.

These four bodies had an added significance, however. In Galileo’s time, Earth was considered to be the centre around which all other celestial bodies revolved, but here was evidence to the contrary: the Medicean stars, quite clearly, orbited Jupiter.

As Galileo continued to scan the sky he noticed other phenomena too that seemed to chip away at the Earth-centred model (read more about this below) and the established view of the heavens being perfect and unchanging.

He saw that the Moon was covered in craters, suggesting that imperfections did exist.

He quickly published his findings as a book – The Starry Messenger – together with a gushing preface dedicating these discoveries to the Medicis.

This tactic worked well. The Medicis did indeed become his new patrons and he was able to leave university teaching and become a court astronomer and mathematician.

Galileo made more discoveries: he was one of the first Europeans to recognise sunspots as being part of our star, more evidence against the idea of heavenly perfection.

He also observed that Venus went through a full set of phases. The Earth-centric model was correct, Venus should only ever show crescents.

Putting the Sun at the centre of the Solar System

With all this evidence supporting the Copernican model, which placed the Sun at the centre instead of Earth, Galileo started to think about publishing.

He arranged meetings with Church leaders, who advised simply to present both sides as alternative theories, not right and wrong.

So Galileo set about writing the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief Systems of the World, in which his character Filippo Salviati put forward arguments for the Copernican model, while another, Simplicio, argued against it.

In retrospect, putting the words of the Pope into the mouth of a character called Simplicio was an error of judgement. It did not go down well.

Galileo’s publication was badly timed. The new Protestant religion was already threatening the authority of the Catholic Church, which was fighting back in what would become known as the Europe-wide Thirty Years’ War.

Dialogue, published in the middle of the conflict in 1632, and the Pope’s reaction to it, must be seen against this backdrop.

In 1633 Pope Urban VIII summoned Galileo to Rome. Galileo was put on trial, and presented his evidence. He showed he’d been given permission to publish, but still had to recant and was put under house arrest.

Compared to other Inquisition punishments, this was getting off lightly.

Galileo died a prisoner, but not before he had written and smuggled out what many considered to be his greatest work, Two New Sciences.

The book deals with subjects we would now call physics, namely mechanics and the laws of motion. It would indirectly influence Newton who, coincidently, was born the year Galileo died.

The Galilean moons, the most obvious of Galileo’s discoveries and achievements, are only a fraction of the legacy he left behind.

Galileo and the Copernican model

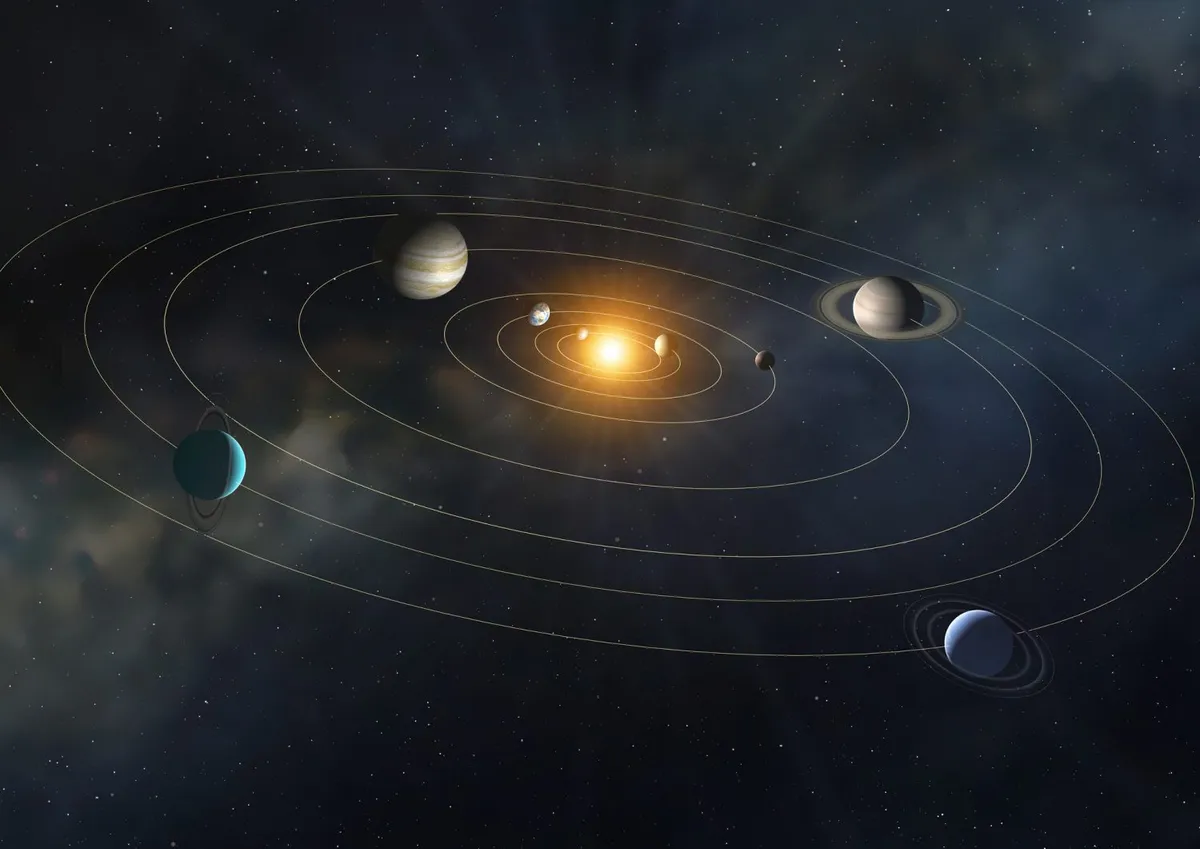

In Galileo’s day, the standard model of the heavens was the geocentric one, which placed Earth at the centre of all other celestial bodies.

In this model, also known as the Ptolemaic system (left), each planet moves according to a complex system of concentric spheres.

Beyond the planets were the fixed, unmoving stars. In this system Earth was the place for mistakes, while the heavens were perfect and unchanging.

This was a model originating in Ancient Greece, developed by Islamic scholars, and Christianised by the Catholic Church.

The Copernican model, which Galileo came to support, was quite different. Put forward by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543, it placed the Sun at the centre of the heavens, orbited by the planets, some of which were orbited by moons.

None was required to be perfect or unchanging.

Dr Emily Winterburn is a science historian and museum curator. This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.