What would a future visitor to Mars see during a night's stargazing? What do the stars look like on Mars?

What does the Sun look like? How far is Mars from the Sun?

Would Mars even be a good place to do amateur astronomy?

At first glance the answer to this last question would be a resounding ‘yes’. For a start there are very few cloudy nights on Mars.

We know it does have some clouds because they have been photographed by every orbiter, rover and lander that has ever been there, and occasionally Mars dust storms brew up that can cover the whole sky for months.

The winds on Mars are also something that planetary scientists are keen to learn more about.

Generally speaking the Martian night sky would usually be as clear as a clear desert sky here on Earth.

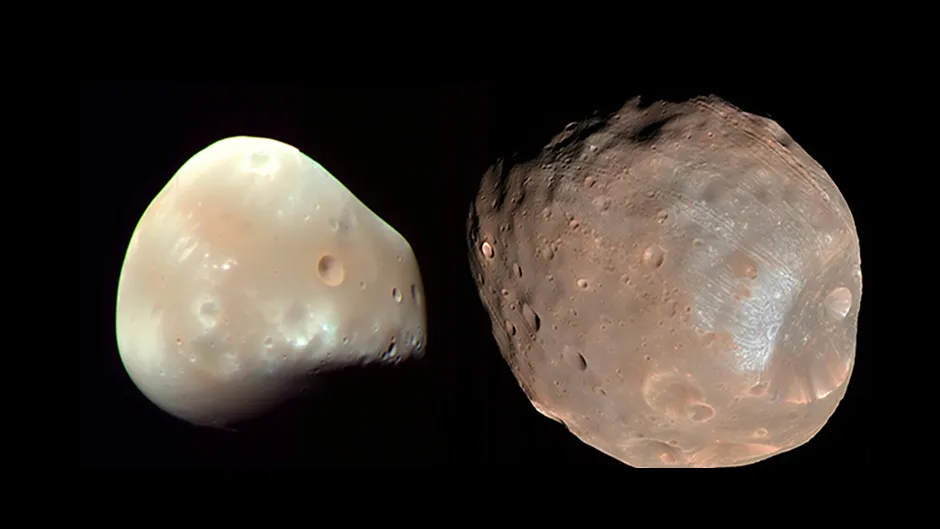

You would see two moons - Phobos and Deimos - in the Mars night sky instead of one.

And there would be a lot less interference from satellites: it's likely to be a long time before Mars’s night sky is crawling with trains of Starlink satellites.

On the downside, twilight lasts longer on Mars because of all the extra light-scattering dust in the air.

That same dusty atmosphere will also reduce the brightness and visibility of the stars at low altitude, just as low-lying fog does here.

What the sky looks like from Mars

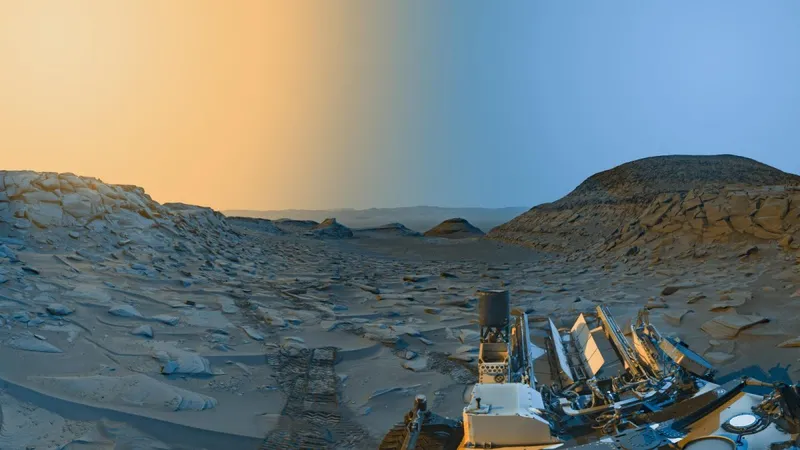

Emerging from the base at dusk, the first thing you would see in a Mars night sky over the rocky landscape would be a beautiful sunset.

On Earth, sunset skies are painted a Turner-esque palette of copper and gold, with the Sun looking like a bloated orange ball.

On Mars, thanks to the dusty atmosphere, you would see a sunset dyed purple and blue, with the faraway Sun reduced to a shrunken blue coin before it set behind the extinct volcanoes silhouetted on the horizon.

Photos taken by the Curiosity rover suggest that once the Sun had set there’s a good chance you would see streaks and curls of silvery-blue noctilucent clouds shining in the twilight, perhaps even a display putting anything seen in our own summer skies to shame.

Depending on the time of year, you might also see an ‘Evening Star’ shining in the lavender-hued twilight.

Not Venus, but Earth, a strikingly-bright spark of silvery blue, which at its best would blaze brighter than mag. –2.5.

If Earth was showing a full or gibbous phase, through your telescope you would see its familiar green continents and blue oceans on the dayside, and the lights of its cities glinting on the nightside.

And just imagine what an incredible sight a crescent Earth would be through your highest-powered eyepiece.

As the sky darkened, the stars in a Mars night sky would look reassuringly familiar. Mars is so close to Earth that none of the stars would look any brighter or fainter than they do from Earth.

As there is no shift in parallax to rearrange the constellations into new shapes, you would still see Cassiopeia, Orion the Hunter, and all your other favourites.

Read our guides to the best winter constellations and the best summer constellations.

However, if you’re a Martian you might know them by different names, or might have totally different constellations altogether.

Native-born Martians of the future will almost certainly re-draw the night sky to celebrate their own history and key figures.

However, as you set up your telescope a problem would quickly present itself: Mars has no ‘North Star’, like Polaris here on Earth, to align on.

Instead, its axis of rotation points at an unremarkable area of sky close to Alderamin (Alpha (α) Cephei), the brightest star in Cepheus. Deneb (Alpha (α) Cygni) is the closest bright star to Mars’s northern celestial pole.

Observing the moons from Mars

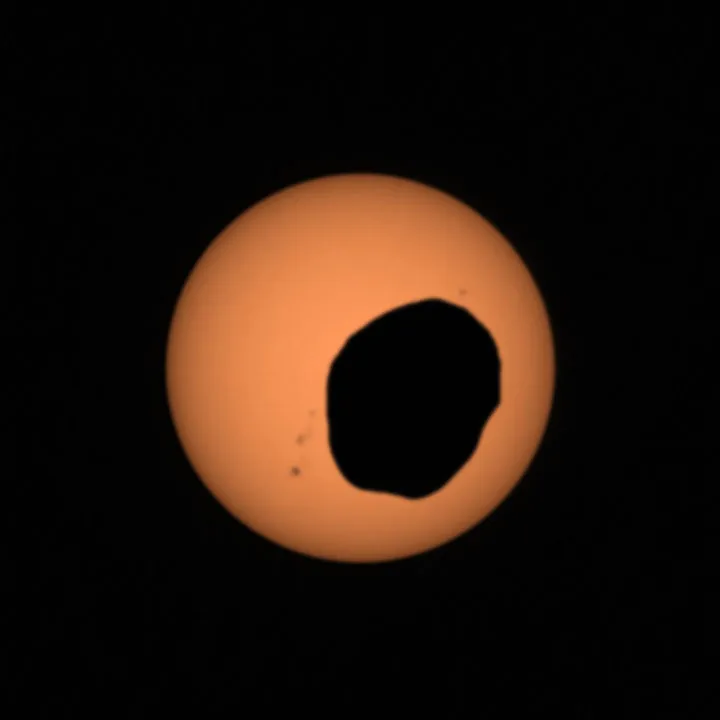

Our Moon crawls relatively slowly across the heavens. In contrast, Mars’s two moons Phobos and Deimos move far more rapidly across the sky.

To the naked eye Phobos would resemble a pale pebble one third as wide as Earth’s Moon, while Deimos would appear more like a bright star. It's also worth considering the unusual orbit of Deimos.

Both Martian moons would shine brightly enough to cast your shadow on the rocks and dust dunes around, as you watched them drift overhead.

And, as the moons move across the Mars night sky, if you could keep them in your telescope’s field of view, it would reveal their irregular, lumpen shapes and largest craters.

Planet-spotting on Mars would be great fun. Although Mercury and Venus would be fainter than they appear from Earth, Jupiter and Saturn would sometimes appear much brighter.

When the two gas giants were at their closest to Mars both would show fascinating detail through your telescope.

With no light pollution or bright Moon to dim the Milky Way, it would be a spectacular sight from Mars.

Just imagine standing on the crumbling edge of the great Valles Marineris, or the lofty summit of towering Olympus Mons, and seeing the Milky Way painted across the sky, stretching from horizon to horizon, its length clotted with frothy star clouds.

Meteor showers on Mars

As you stood there hypnotised by the beauty of the Milky Way you might see a meteor zip across the sky. Despite Mars having quite a pathetic excuse for an atmosphere, it is still thick enough to produce meteors.

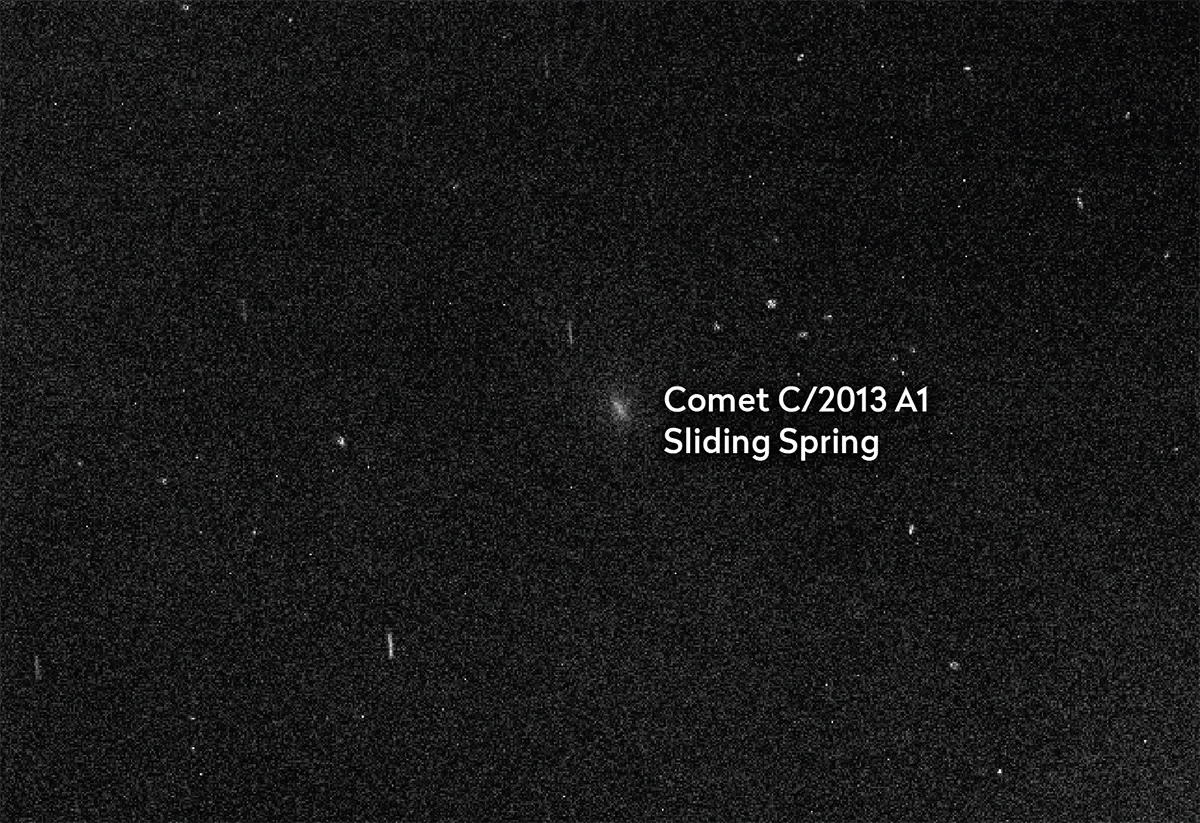

If you had been standing beside Opportunity in 2014 when Mars passed through the tail of Comet Siding Spring, you would have seen a display of shooting stars rivalling the famous Leonid storms of the past.

Such events are very rare of course, but research suggests Mars has its own meteor showers, although they don’t occur on the same dates as Earth’s.

If you’re a deep-sky observer you would also be able to see all your favourites from Mars.

However, your views of incredible sights such as the Orion Nebula, the Andromeda Galaxy and the Pleiades star cluster might be ruined by the fact that it would be difficult to get close to your telescope eyepiece due to the bulky visor of your spacesuit helmet.

Eventually the sky would begin to brighten, a violet-blue glow spreading over the eastern sky until the Sun burst over the horizon, flooding the landscape with light.

The Martian stars would be snuffed out one by one, until only the brightest planets remained, then they too would fade away, leaving the sky a blank, orange-pink dome once more.

And another Martian day would begin.

Doing astronomy and stargazing on Mars

Future amateur astronomers on Mars will have to be tough and resilient.

They might not have to cope with the frustration of cloudy nights like their terrestrial counterparts but they will have other, greater, challenges.

For a start, they will have to see and do everything cocooned inside a spacesuit protecting them from the inhospitable Martian environment.

Night-time temperatures on Mars can drop to -90°C, so fingerless gloves and a woolly hat are not going to be warm enough.

Even before going outside to stargaze they will have to spend hours suiting up and then cycling through an airlock.

Once outside, the real challenges will begin. Sadly, there will be no escape from light pollution, even on Mars.

Stargazers will have to get away from light produced by the base, but not so far away that their safety is put at risk.

Once their vision is dark-adapted they will have to view the starry sky through their helmet visors, which might distort the stars or affect their colours.

Using binoculars or telescopes will be difficult for the same reason, although it is possible they might be able to use some sort of visor attachment to let them look through the eyepieces of such observing equipment.

Astrophotography on Mars

As for astrophotography, the DSLRs used back on Earth won’t cut it on Mars.

These cameras aren’t designed to be used in such a dusty and lethally cold environment, and would probably die within a few minutes of being put on their tripod.

But a camera specially designed to be used on Mars would take fantastic images of the stars, planets and Milky Way shining above the planet’s jagged mountains, meandering canyons and towering volcanoes.

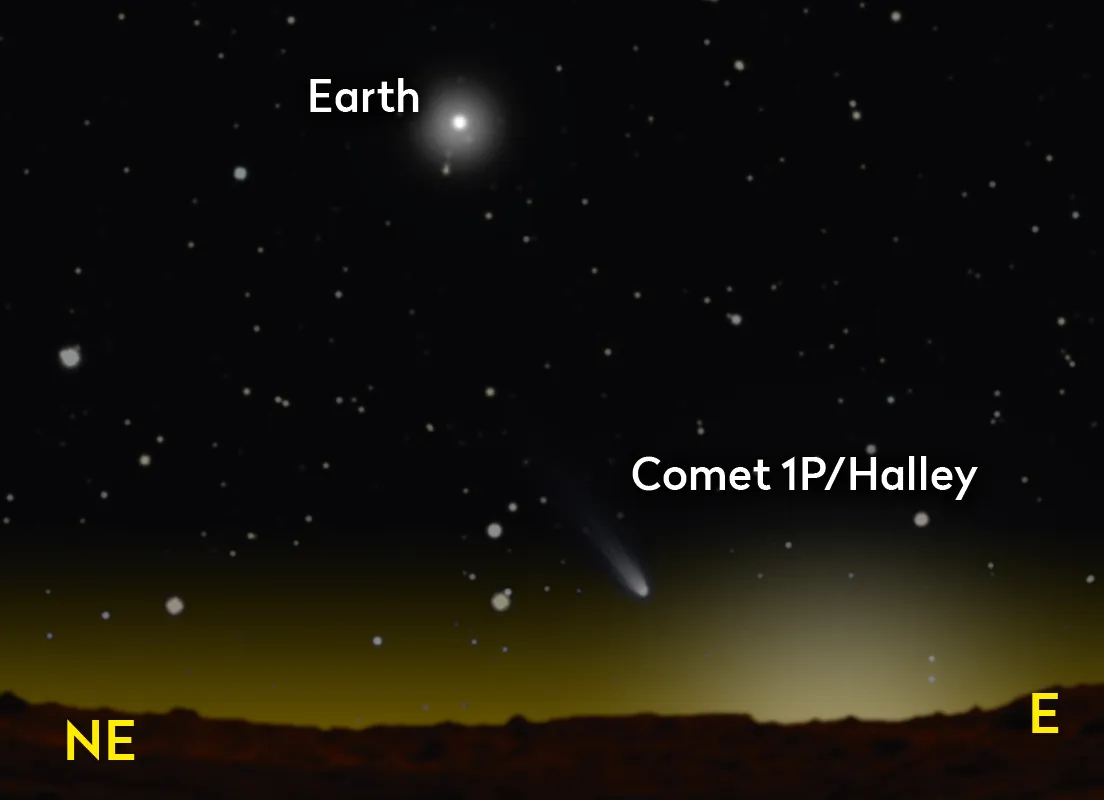

Perhaps the winning image of the Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2061 competition will be a twilight photo of Halley’s Comet shining below Earth, high above the dust-covered Opportunity rover.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.