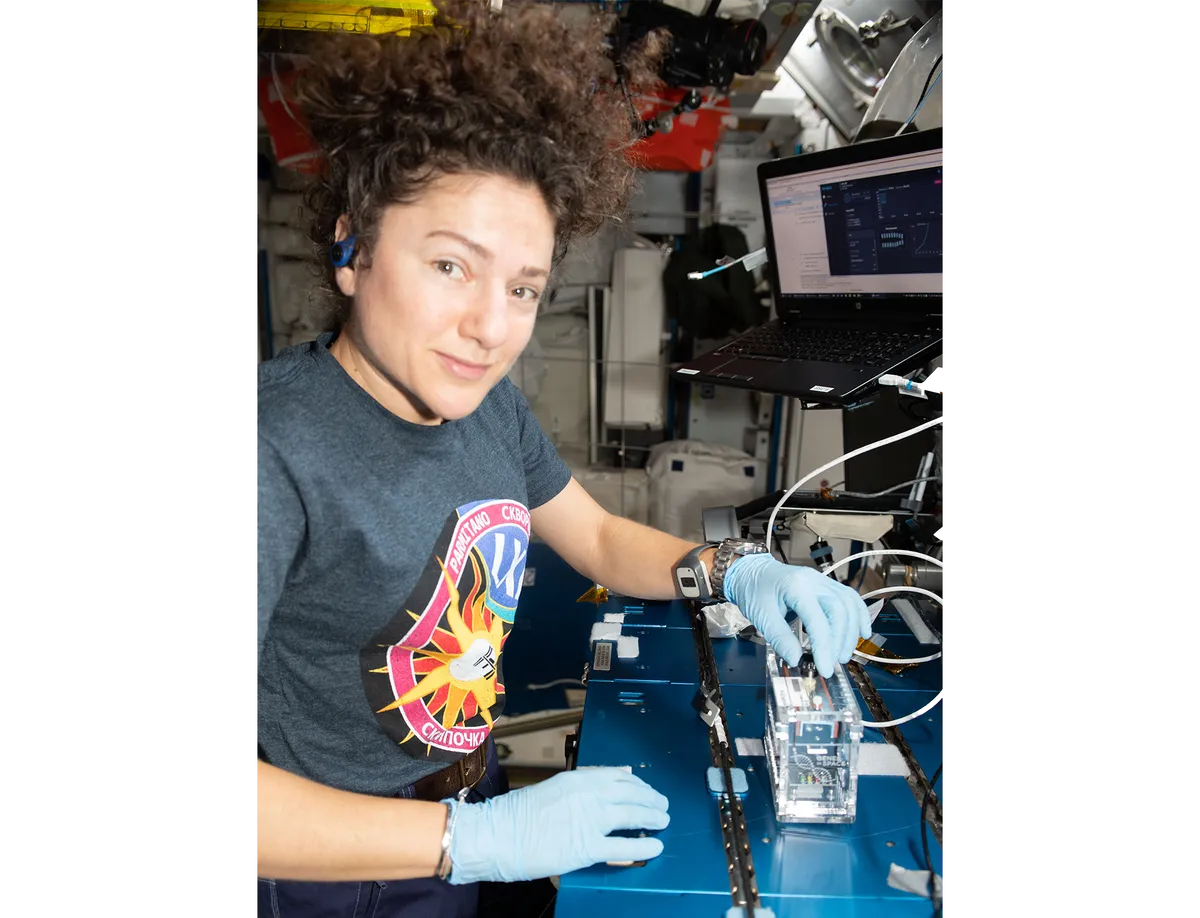

It's a tough life, being an astronaut. Not only do you have to contend with living and working in zero gravity, conducting science experiments and going through the trauma of launch and re-entry, but the human body also undergoes genetic changes in space that scientists are only beginning to understand.

A case in point is former NASA astronaut Scott Kelly's year in space, during which genetic changes to his body were compared against his Earth-bound astronaut twin Mark Kelly, as a means of getting a better idea of the damage done by zero gravity and radiation.

More human spaceflight

But if we are to establish a permanent human settlement on the Moon, and if humans are to survive the journey to Mars, geneticists will have their work cut out deciphering the changes wrought upon our gene codes by long-duration periods of living and travelling in space.

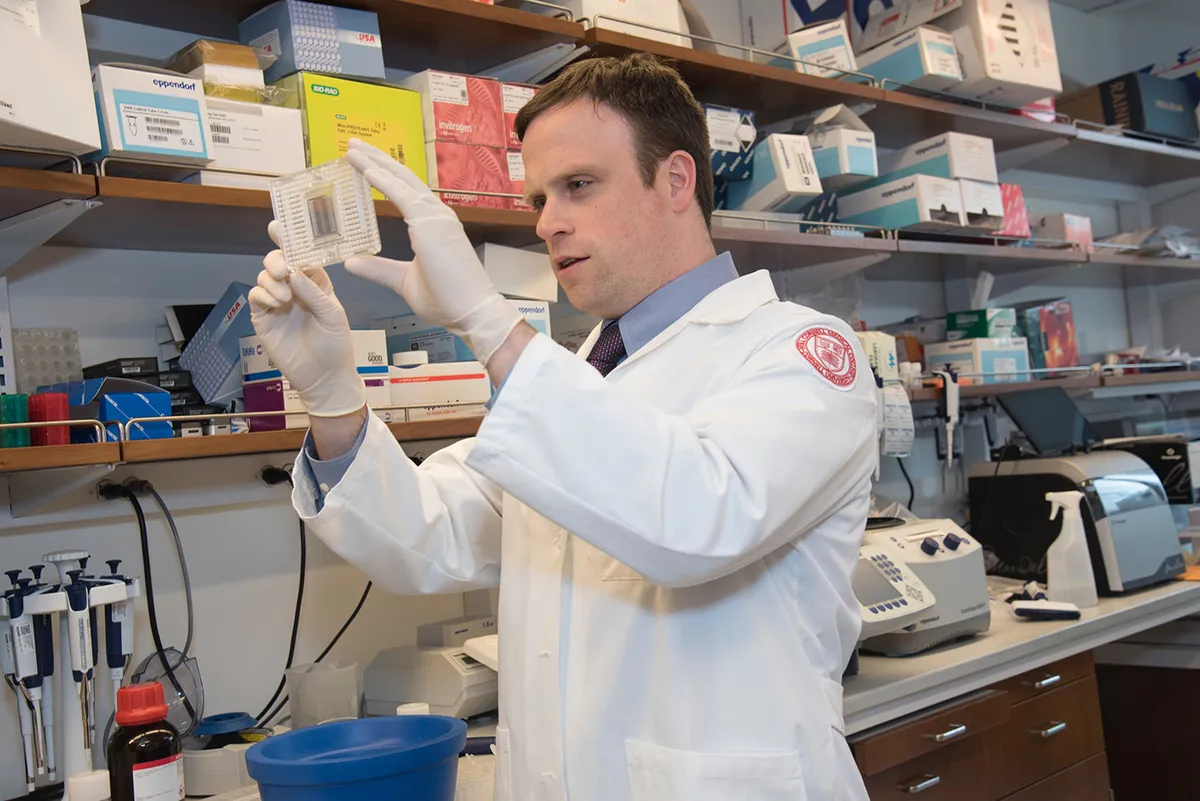

Professor Chris Mason is a space geneticist and author of The Next 500 Years, published by The MIT Press.

In the book, he argues that we don't need to terraform a hostile planet like Mars in order to be able to build a permanent human settlement.

We could instead manipulate human genes to make the Martian atmosphere more palatable.

We got the chance to speak to Prof Mason about how genetics can make life in space easier on the human body.

What does spaceflight do to the human body?

Space is rough on the body: the bones start to decay – you can actually see calcium coming out in urine for most astronauts.

Some of your veins and arteries can get inflamed, because you have a lot of radiation coming at you and the fluids move around your body in different ways.

It’s hard on the body but we are extraordinarily adaptive. Even though we see damaged DNA and dying cells, we see regeneration and adaptation.

We can see that the body responds quickly to space flight.

What are the biggest dangers for astronauts?

The number one issue for astronauts is probably radiation.

On the International Space Station (ISS), you’re still within the protective blocks of Earth’s magnetosphere yet you’re still getting the equivalent of about five full body X-rays of radiation per day, and that starts to add up.

There’s also the change in gravity and the isolation.If you have a bad day on Earth, you can take a walk outside, but if something goes wrong in space you can’t do that.

Part of the isolation is that there’s nowhere to go.

How can genetics prevent damage to the human body?

We already modify human cells therapeutically and use them routinely today for immunotherapy to treat diseases like cancer.

Now we’re thinking about creating temporary – or possibly permanent – genetic changes to help enable features that we already have in our body.

It may seem like science fiction, but it doesn’t require any new strange technology or new chromosome that we don’t already have in our genome.

You could turn on genes just as you need them. For example, if you have a higher burst of radiation, we could increase DNA repair enzymes for just a little while and then bring them back down later.

We can learn from evolution to enable us to survive in places that we currently can’t.

What genes in the body could you switch on?

For example, if you are vitamin C-deficient (from not eating enough limes) you might get scurvy.

However, there is a gene for synthesising vitamin C that’s in our DNA. It’s just been inactivated through evolution.

We could make all of our own vitamin C – there are other primates that do this.

There are things we’ve learnt about our genome that we have found and said "Well, what if we just put that back to the way it used to be?"

We wouldn’t just deploy biological adaptation mechanisms to survive, we would still need protective suits and hardware and pharmacological interventions; but we’re adding another layer.

What did the Scott Kelly experiment teach us?

I was the head geneticist for the study. We saw so many things change, everything from his DNA to his vitamin levels.

His eyes changed and so did the microbes in his stomach, while the artery in his neck got bigger and he got two inches taller.

It was extraordinary, because almost everything went back to normal back on Earth, given a few days.

We’re expanding the study to future missions, to look at other astronauts and see what happens to the body, to learn how we can make it less stressful or painful.

Why should humans adapt to live in space?

It’s a sense of duty. Humans have a unique duty that no other species have.

As far as we know, we’re the only species that have this unique awareness of extinction.

It’s only humans who can understand what it means for a species, or even for all of life, to go away. That means it’s only us that can prevent it.

Our track record on this is mixed as humanity goes. I think life is very precious and so I’d like it to last longer than just the lifespan of this planet or the Solar System.