Everyone loves black holes, especially when they’re doing classic black hole things like ripping stars apart and consuming them whole.

The authors of this month’s paper, led by Fulya Kiroglu from Northwestern University just outside Chicago, use powerful simulations to look at what happens when a Sun-like star, minding its own business, encounters a black hole that outweighs it by a factor of between a hundred and a thousand.

I should say at the start that it’s not very clear that black holes of this intermediate size actually exist.

We know smaller ones do, formed in supernovae at the end of a massive star’s lifetime, and gravitational wave experiments have detected mergers of black holes that add up to about 100 solar masses.

We also know that supermassive black holes weighing millions of times the mass of the Sun live at the centres of galaxies.

But in between – maybe – are black holes that form from the deaths of the most massive stars, or via merging with other black holes in the middle of dense star clusters.

In either case, one way of detecting these elusive beasts would be to spot them as they grow by swallowing their stellar companions whole.

Consuming a star should make a mess, and it has been suggested that bright sources of X-rays found in the right sorts of star clusters might be caused in just this way.

Bbut that means we need better simulated models of what exactly happens when a star comes close to the black hole.

So what happens when a black hole swallows a star?

The answer, the team find, is that ‘it varies’.

If the star keeps its distance, then it might get away with little lasting change.

If it gets too close, though, it will be ripped apart.

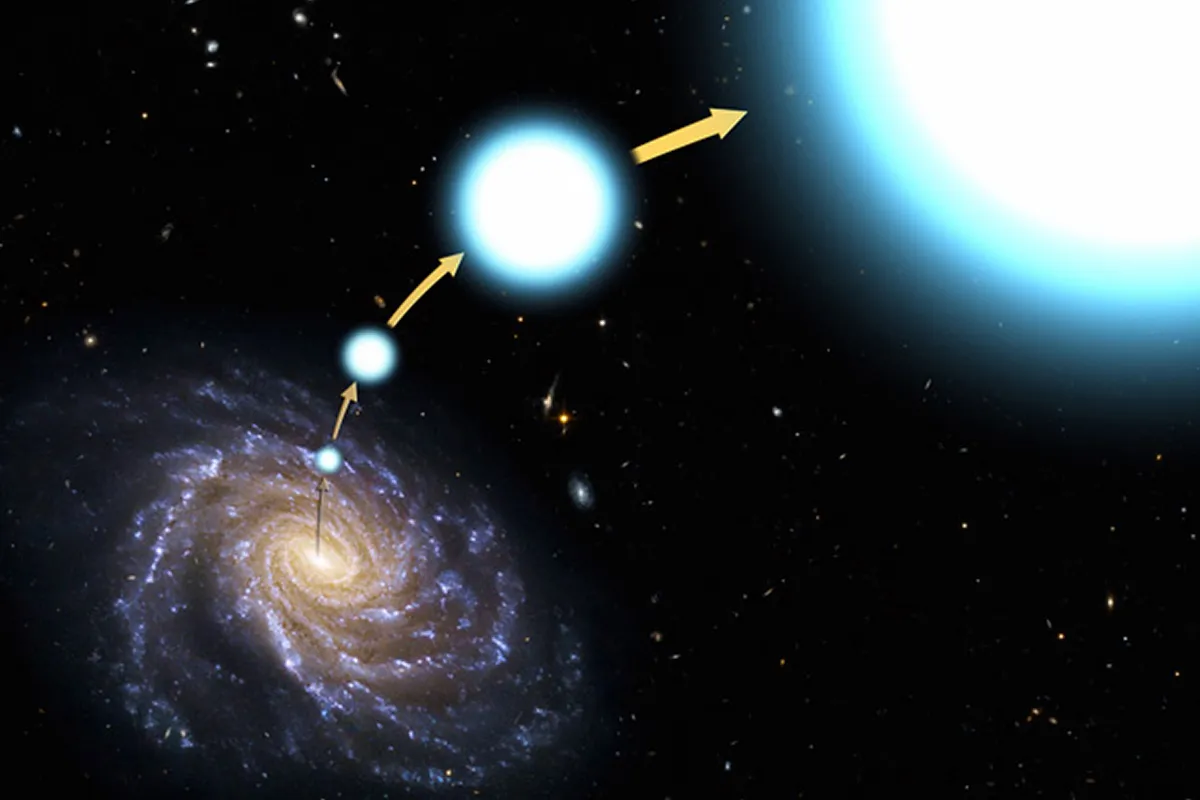

The simulations show that even a first passage close to the black hole, prior to being captured into orbit, will see the star lose a lot of mass.

The disrupted star may even be ejected from the system after this initial encounter, or captured into an orbit where the black hole will cannibalise ever more of the star’s mass on each subsequent passage.

This seems to happen again and again. In one example looked at by the researchers, a star encountering a 10-solar-mass black hole swings by 16 times before what’s left of it is ejected back into the cluster.

For larger black holes, the number of orbits a star can survive is smaller, with a star orbiting around a 100-solar-mass black hole withstanding just five passages.

This is exciting; it means that if we can detect X-ray flares from the material being ripped from the stars, then we should see a repeating pattern of such events marking the position of a black hole and be able to work out how massive it is from counting the number of flashes.

The simulations also show that each flare should be brighter than the last, creating a distinct signature that could be used to recognise these systems.

Of course, more work – by which I mean creating more simulations, including stars of different sizes, masses and ages, as well as more details of the processes in play – is necessary.

But in a year or two we could be hearing news that we’ve finally filled in the missing link of black hole evolution, thanks to the flashing X-rays produced as examples consume stars.

For more on tidal disruption events, read our coverage of AT2018fyk.

Chris Lintott was reading Tidal Disruption of Main-sequence Stars by Intermediate-mass Black Holes by Fulya Kiroglu et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2210.08002.

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.